Councilmember Rivera wants to freeze funding to the City’s largest anti-displacement program, imperiling projects led by communities of color.

The Seattle City Council placed two highly consequential items on the agenda for yesterday’s meeting, but ultimately pulled both after more than 100 people testified in opposition.

Ahead of Tuesday’s meeting, Council President Sara Nelson (Position 9) announced plans to pull her legislation to lower the minimum wage for gig workers, including on popular delivery apps like Uber Eats and DoorDash, saying she wanted more time for stakeholder work.

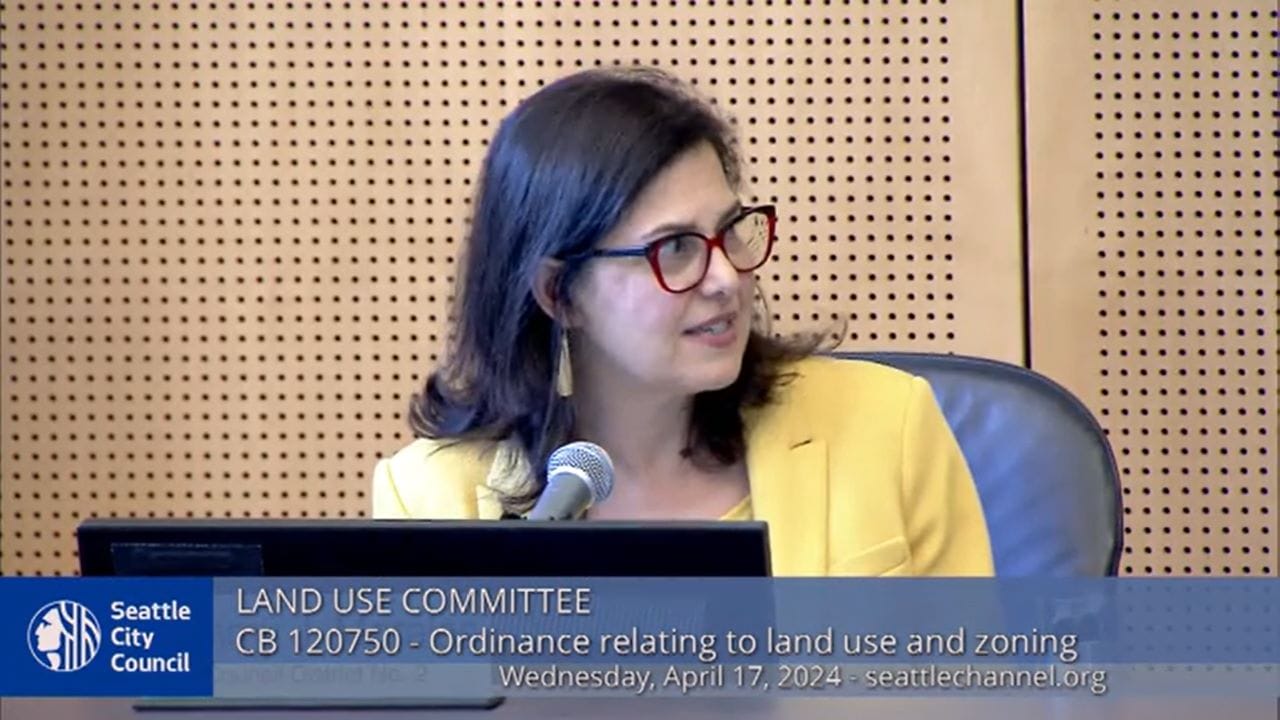

During the meeting, Councilmember Maritza Rivera (District 4) also pulled a routine budget bill from the agenda, which included an amendment from her that would have frozen $25.3 million in 2024 Equitable Development Initiative (EDI) funds. Her budget proviso also would force recipients to spend 2023 awards or risk losing them, add labor-intensive reporting requirements, and direct the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) to conduct a review of the program.

Public comment lasted nearly three hours and was overwhelmingly against both proposals. Advocates and nonprofit leaders vented their frustrations and argued for the continued need for the program to fight displacement of communities of color, given Seattle’s super-charged real estate market. Many people testifying argued Rivera dropping her amendment on Friday before the Memorial Day long weekend amounted to an attempt to stifle public debate.

Both proposals will return next week at the June 4 council meeting.

Councilmember Tammy Morales, who represents District 2 (where many EDI projects are located), came out hard against the amendment ahead of the meeting.

“This amendment would preemptively undermine commitments that Seattle has made to mitigate displacement for communities of color,” Morales said in a press release. “It would endanger funding for community organizations doing work everyone on this Council says they agree with, like supporting small businesses, building affordable housing, and addressing racial equity. This is not good governance. If this amendment passes, our community partners will lose trust with the City of Seattle and our commitment to anti-displacement strategies.”

Amy Sundberg laid out the issues with Rivera’s amendment in an op-ed that first ran in South Seattle Emerald and also in The Urbanist. Since the council is heading into a budget season with a $258 million deficit it has thus far failed to account for, either with new revenue or with concrete plans to cut spending, the move was interpreted as a pretext to cut EDI funding this fall.

Rivera and her allies on Council took issue with the criticisms they were hearing, contending that opponents had spread misinformation.

“I’ve moved to amend the agenda to remove Council Bill 120774 in order to give time to correct information that was irresponsibly given to community about my proposed amendment,” Rivera said. “Let me be clear, the amendment does not cut the EDI program. The amendment does not pull money away from existing projects. All 56 ongoing EDI projects will remain funded that was made clear in the amendment. I’m deeply disappointed that the objective of this amendment has been grossly mischaracterized.”

Councilmember Cathy Moore (District 5) agreed with Rivera and similarly blamed a “fearmongering” misinformation campaign for turning this into a controversial proposal. She seemed to suggest another week or two could win over many of the critics worried this was a budget grab that would imperil many EDI projects.

“The reason that I think it should be taken off is that there has been so much misinformation and frankly fearmongering that’s been sent out there into the community,” Moore said. “And I think that we owe it to everybody who showed up here today.”

Ultimately, Rivera was able to secure the votes to table her amendment, although Morales, Dan Strauss (District 6), and Joy Hollingsworth (District 3) opposed the motion. Strauss opposed the move on the grounds that the underlying legislation shouldn’t have to wait for an amendment that could be advanced through other avenues. Morales intimated that it was Rivera who was mischaracterizing her bill and declining to own her policy decision.

“I don’t know what benefit would accrue from tabling this legislation,” Morales said. “We had over 3,000 emails over the weekend. And frankly, if you want to propose legislation that rolls back commitments made to Black and Brown communities, at least have the courage to stand by your legislation and vote on it or acknowledge that you made a mistake and withdraw it.”

Furthermore, Morales made the case that EDI projects being slow to come together should not be a surprise given their complexity, especially for organizations new to the process.

“The EDI program funds projects that are at various stages. We heard from people for three hours about why it takes so long,” Morales said. “These are not practiced developers who are participating in this program. These are community-based organizations who want to create senior housing or want to create a cultural anchor for their constituents in their community. They don’t understand and have the expertise of traditional developers. That’s why this takes so long.”

Councilmember Hollingsworth also opposed the motion on principle, specifically citing recipients of EDI funding like the Central Area Senior Center, Wa Na Wari, Hip Hop Is Green, and Africatown Land Trust. “Councilmember Rivera, I know your heart is in the right place, but I also know these have unintentional consequences, and I don’t think this is sending the right message for our Seattle values about supporting community,” Hollingsworth said.

Getting a shovel-ready project entails navigating numerous bureaucratic hurdles, from braiding together multiple streams of affordable housing funding (each with their own distinct requirements) to making it through Seattle’s famously fussy permitting system.

“It takes three or four years, sometimes, to cobble together the funding for site acquisition. It takes another three or four years, sometimes, to cobble together the funding to actually do the construction projects — and that’s if you are already an experienced developer, so it is not surprising at all,” Morales said. “The whole purpose of this program was intended to support and provide assistance to organizations that are trying to do the right thing for their communities, to create housing, to create childcare, to create cultural centers, to create senior programs, or senior housing.”

In front of Seattle City Hall, the empty “Civic Square” block — a giant pit since 2005 — is a testament to how long even well-resourced private developers can take to put a development project together. That some councilmembers believe four months is enough time for nonprofits to do so perhaps speaks to some unfamiliarity with how development actually works. Rivera alluded to her knowledge gap in previous comments laying out her opposition to Morales’ Connected Communities program, which proposed to set up zoning incentives for affordable housing in high-displacement-risk areas of the city.

“So we’re all trying to come up to speed with all of those programs,” Rivera said in February. “And so this is another program on top of the ones that the city does administer that we really need to dig into. I think there’s a level of discomfort to start a new project where we’re not clear on how well the existing projects and incentives that we’re currently doing at the city are doing, so I want to be transparent and honest about that.”

Rivera did not single out the Equitable Development Initiative at the time, but it now appears that was what she was alluding to.

Like several public commenters, Morales took issue with the extra scrutiny that projects intended to serve disadvantaged communities of color was receiving compared to other programs also facing delays, such as infrastructure projects at the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT).

“We don’t ask the Office of Housing to put their money back in the general fund or back in the pot because their capital projects are taking a long time. We don’t ask SDOT to put their money back in the pot because their capital projects are taking a long time,” Morales said. “It is interesting to me that the programs that are meant to assist with reversing harm done to communities of color are more closely scrutinized than other programs in the city and are consistently at risk of being defunded more than other programs in the city.”