Community Transit recently took ownership of a hydrogen-powered bus, making it the first transit agency in the Puget Sound region to procure one. The vehicle is part of a pilot effort to test out fuel cell electric bus technology, an alternative type of zero-emissions bus (ZEB) in the agency’s fleet. Community Transit already has a battery-electric bus (BEB) it has yet to phase into service. Both ZEBs are expected to carry riders in the coming months.

In April, Community Transit issued its long-term plan to transition to a 100% zero-emissions fleet by 2044 — though that transition could be realized sooner if things go well. Implementation of the plan is expected to happen incrementally, as the bus fleet is replaced and expanded over the next two decades.

As part of the plan, Community Transit conducted an assessment on ZEB technology to determine how many service blocks could reasonably be achieved with BEBs. That assessment found that by 2050, 73% of service blocks (essentially routes using 40-foot buses) could be filled with BEBs without resorting to challenging service solutions, such as pulling buses out of service for midday charging at base or deploying a second BEB to continue service. The estimated 27% gap in service blocks, which is mostly on routes using 60-foot buses, forced the agency to consider another zero-emission technology solution in the form of fuel cell buses.

Under the agency’s transition plan, all future bus procurements will be zero-emissions. This portends a major rollout of ZEBs beginning in 2027 with battery-electric buses, and fuel cell buses entering service somewhere between 2029 and 2030.

Modeling suggests that Community Transit could reach a 100% zero-emissions fleet as soon as 2038 with a mixed ZEB fleet consisting of 191 battery and 90 fuel cell buses. As part of service growth plans, the agency would need additional vehicles by 2050, increasing the BEB fleet to around 210.

Interim estimates for a 30% zero-emissions fleet by 2030 indicate that the agency would need 50 BEBs and 25 fuel cell buses, costing about $158 million in vehicle and support infrastructure. Meanwhile, the cost of the full conversion to a ZEB fleet by 2038 is estimated to reach $560 million.

Community Transit is taking a methodical approach to electrification by trying out multiple technology options before committing to a decarbonization path, unlike King County Metro and Sound Transit, who have gone all in on battery-electric buses. Metro’s northern neighbor appears to be giving fuel cell buses a real chance to meet electrification, financial, and service objectives.

Based upon agency assumptions, Community Transit expects that fuel cell technology will be a better fit for heavier duty routes which operate more service hours. That includes routes like the Swift bus rapid transit lines that operate at a high frequency, seven days a week, on long corridors with full daily spans of service.

Fuel cell buses have obvious operational benefits over conventional battery buses, such as higher fuel capacity faster refueling, and can operate in more extreme weather conditions, resulting in longer ranges and more daily potential use. Fast-charging solutions are increasingly available for BEBs, including en route wireless induction charging, but it still isn’t enough to meet the needs of most workhorse bus routes.

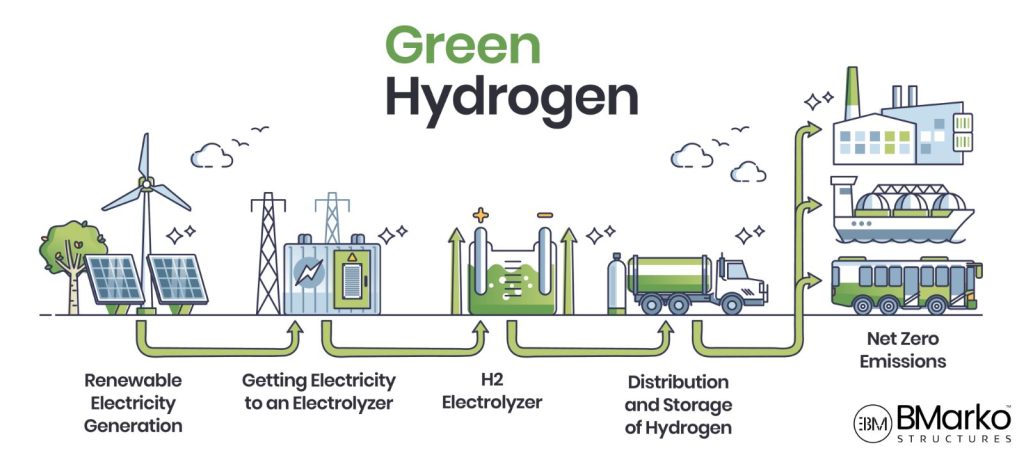

The hydrogen that powers fuel cell buses usually comes in a compressed gas form that is pumped into tanks onboard buses. When the fuel is released into fuel cells, oxygen from the air is pulled in, and the chemicals react through a catalytic process that creates electricity, plus water vapor (H2O) as a byproduct. As part of this process, heat is also generated, which can be transferred to warm the occupied portions of the vehicle. Electricity charges onboard batteries and powers bus systems, including the engine.

In new fuel cell buses by New Flyer Industries, vehicles operate at a higher efficiency through regenerative braking. This recovers kinetic energy from braking to recharge batteries.

However, some environmentalists criticize hydrogen fuel as a zero-emissions solution due to the emissions generated in its production and transport.

Currently, most hydrogen in the United States is produced from methane (CH4), also known as natural gas or fracked gas, through a process called steam-methane reforming that separates hydrogen atoms from carbon atoms. This “grey hydrogen” method creates harmful byproducts, such as particulate pollution and carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas for which ZEBs are intended to solve. Additionally, most hydrogen fuel is transported by trucks which usually aren’t zero-emissions vehicles, often over long distances, introducing another source of carbon emissions into the equation.

Nevertheless, production of fuel cell buses involves less embodied carbon than BEBs, where the manufacture of batteries to power the bus drive up the carbon footprint. Moreover, government programs are investing in green hydrogen solutions that transit agencies hope to deploy in the coming years. Under the green alternative, scientists aim to use renewable energy to harvest hydrogen via the electrolysis of water, which, if achievable at scale, would be much greener than using fracked gas as the input.

For now, Community Transit will be procuring conventional hydrogen fuel and trucking it from California to their base facilities in Snohomish County. But the agency intends to move toward green hydrogen in the future — and to use the least carbon-intensive hydrogen fuel available in the interim.

“We are currently exploring long-term, sustainable solutions for establishing a hydrogen supply nearby,” Monica Spain, an agency spokesperson, told The Urbanist. “Being in the Pacific Northwest, we have a clean electrical grid, so we are uniquely positioned in this area to take advantage of that clean energy source.”

Initially, the BEB will have access to a cleaner source of energy since Community Transit facilities are powered by Snohomish County Public Utility District No. 1, which gets at least 96.5% of its electricity from clean power.

In the next few months, both of Community Transit’s ZEBs will be deployed on various routes for testing and to evaluate performance. Riders trying to catch them may want to use an app like Pantograph to determine when and where they are in service at any given time, since they won’t necessarily be assigned exclusively to one or two routes. Community Transit hasn’t given specific dates on when they’ll go into service just yet, but the agency said that the BEB should start regular service sometime in the summer and the hydrogen fuel cell bus will follow sometime in the fall.

Both zero-emissions buses that Community Transit will be trialing are 40-foot low-floor vehicles. New Flyer manufactured the fuel cell bus whereas the BEB comes from Gillig. The yellow and blue paint jobs should set them strongly apart from the rest of the fleet, denoting them clearly as hydrogen and electric, respectively.

In terms of range, Community Transit is hoping to get about 200 to 250 miles out of the fuel cell buses (New Flyer touts a range of up to 370 miles) while the agency is hoping to get around 150 miles on a single charge in the battery bus. Equivalent diesel-hybrid buses usually get 300 to 350 miles on a full tank. Testing out the new zero-emissions buses will help answer questions about range and reliability, and aid the agency in determining how they can best serve environmental and operational goals.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.