In cities like Seattle, where the median home costs $800,000 and can soar above $1,000,000 in many neighborhoods, the land speaks loudly in many languages: residential, commercial, and recreational. What does it say about the peoples’ histories? Does it teach visitors and residents about the indigenous blood spilt in its conquest by the United States? Does it impart lessons on multicultural activism by celebrating Carlos Bulosan’s fight for labor rights, Dorothy Hollingsworth’s work to improve education equity, and Floyd Schmoe’s peace activism against Japanese internment? If so, how loudly does it speak?

The centrality of monuments to this land’s history, and the volume of land they occupy, permits the land to speak louder. How loudly can a space wedged between two sections of NE 40th Street speak? That’s where you’ll find Seattle’s Peace Park commemorating the ethnic cleansing of the city’s residents of Japanese descent.

How loudly does a single grave plot speak? That’s all the commemoration Carlos Bulosan receives from the city. Meanwhile, the soldiers who committed a genocide in his homeland are memorialized by a massive statue in one of the city’s largest parks.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Memorial Park is an exception to this erasure of the region’s injustices, but what does it say that the local civil rights activist Edwin Pratt’s legacy is physically honored by a nothing more than a sign post at a playground bearing his name? When contrasted with the statue of William Henry Seward, which is larger and more prominently displayed than Chief Seattle’s, it seems the urban landscape is attempting to circumvent troubling yet defining aspects of its history.

A visitor might believe the name “Seattle” was invented out of whole cloth, like Idaho, given how little story and space the city has allocated to acknowledging its Indigenous peoples. Apparently, confronting this troubled past is something the city values less than maximizing its real estate values.

Seattle would do well to explicitly and physically respect and memorialize the places where its history has occurred. While monuments to important figures and concepts are useful teaching tools, nothing is quite as impactful as physically confronting a space where historical tragedies have occurred. When we teach history well, we avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, which is very poignant in a time rife with significant political movement to destroy progress, to close and fortify the borders, and to entrench the privileges of the wealthy and powerful.

Other nations have confronted the crimes of their past in far more depth than the United States. For example, Germany actively uses curriculum, laws, and prominent public memorials to teach all sectors of society about the horrors of the Nazi ideology. While it is not a panacea for deeper societal issues fueling support for right-wing extremists (nor fully acknowledging their past, given their reticence to reach an amicable deal with Namibia for the genocide they perpetrated there), it has helped delegitimize fascism in Germany, pushing the center-right from compromising with extremists.

The United States seems to have taken lessons from Germany about its treatment of Namibia, rather than the Nazi state’s European victims: talking heads and history books sanitize the country’s history of chattel slavery, colonialist genocide, racial oppression, Chinese expulsions, Japense internment, and xenophobic policies – if they mention them at all.

Explicitly memorializing history in urban spaces helps prevent these bad actors from papering over a region’s bloodstained past. I gained an intense appreciation for this back in November of 2023, when my fiancé and I stumbled upon a historically significant graveyard and memorial in the center of St. Petersburg, Russia – a city of 5 million people, living in an area four times smaller than King County.

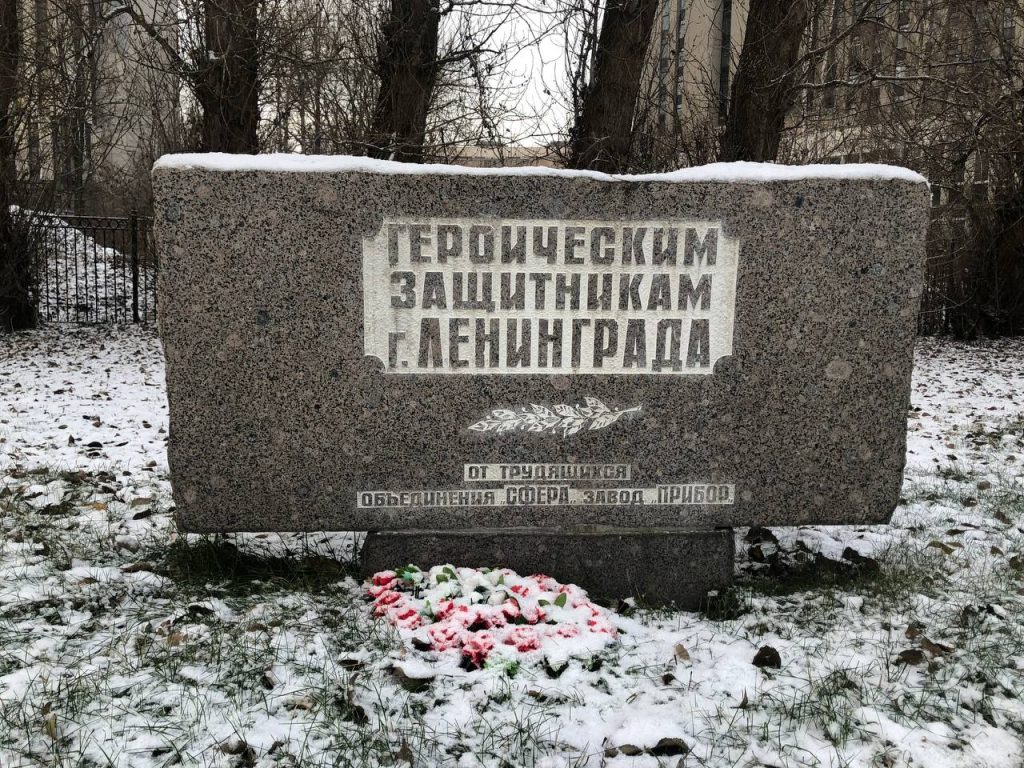

Walking through a park on the way to the metro, we noticed a fenced field of long mounds, roughly a hundred feet long and seven feet wide. The gate told us it was called “The Graveyard on Decembrist’s Island.” Having never seen any graveyard like it, we approached to investigate. Rows upon rows of earthen mounds with obelisks resting in their centers flanked the path to the center. As we progressed, a suspicion about the nature of the mounds steadily crawled its way up my spine and lodged itself into the back of my mind. An inscription engraved onto a massive obelisk in the center of the yard confirmed it: they were the mass graves of people killed during the city’s siege from 1941-1943.

At the far end, there was a normal cemetery with individual graves. We approached and scrutinized the dates on each: 1905-1942, 1889-1942, 1882-1942,1924-1942, etc. The burial place had opened in the midst of the siege and transformed into a mass grave when the land couldn’t hold the city’s dead individually. I imagined the gravediggers realizing the land wouldn’t have enough space, making the dismal calculations, and making the horrific decision to inter the bodies of their friends, neighbors, and colleagues in piles. In perishing, every person buried at this site sacrificed their needs so that others might live. They permitted others to eat the scarce food they would have consumed, soak up the fleeting warmth from burning furniture and peat, and hide from bombardments in the city’s limited shelters. Which is more heroic: dying that your family and neighbors may live, or murdering people in the Philippines and China on behalf of imperialist adventurism?

This site’s unique presence among dense urban housing in the center of a large city can teach us about how to respect the heroes of history. It is a scar inflicted by history, necessarily maintained as tribute to the victims of war and genocide. Were it bulldozed to build a shopping center with some ridiculous name like “The Leningrad Heroes’ Memorial Mall,” the developers would actively and scornfully obliterate history, robbing residents and visitors of social and emotional sense of place. Land where the victims of history fell, fought, or are buried is sacred; it can impart universal lessons unique to the specific historical events of any given region. Paving over these spaces to extract their financial value is sacrilege.

The Duwamish burial ground on Stitici (Foster Island) offers a perfect example for where and how Seattle could honor its history, by more explicitly and respectfully recognizing the sanctity of this specific location in the heart of the city.

At the Graveyard on Decembrist’s Island, any visitor could have appreciated the spiritual impact of the site from its physical cues, but people have to speak English to understand land acknowledgements. The symbols of nations which have inhabited Seattle emblazoned upon stones in dedicated gardens, the tying of prayer cloths to the branches of trees in memorial of the dead, convey the ancestral experiences of the land to speakers of any language hailing from any corner of the globe. Seattle can and should strive to preserve these legacies more impactfully and overtly, paying respect to the memory of its violent and racist historical development, and honoring the enduring legacies of the survivors.

One space where this could easily be improved in Seattle is Cal Anderson Park, where its association with LGBTQ+ rights can only be decoded by those familiar with the figure of Cal Anderson, or those willing to read through every plaque along the AIDS memorial pathway. There are so many ways his legacy could be honored in sculpture and symbolism, even beyond a statue, yet the city seems content to squirrel away a remembrance of his death into a corner.

Urban spaces are more than just places of life and commerce; they are places of history and spirituality, whether we ignore or embrace that fact. To ignore this robs the people of a fundamental human experience, creating in them a void they cannot fill with shorter commute times and increased commercial revenues. To embrace it forms a collective consciousness of our positions in history, preserving the legacies of our community’s ancestors by communicating them in perpetuity. Seattle, and all cities, should use physical spaces to teach history more loudly and impactfully than any classroom instructor ever could.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.