Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) have been headline news as the housing crisis pushes homeowners to seek new ways of battling the affordability crisis. In 2020, there were an estimated 1.4 million ADUs in the United States, according to Freddie Mac. Many are rented out or are providing affordable housing for families.

Washington is no exception. Last year, the state house took action to make building ADUs in urban areas easier, too. HB 1337 took effect in July 2023 and aims to make it easier for residents to convert units like garages into ADUs across the state. These plans were consequently followed up by Rep. Jessica Bateman’s HB 1110, which sought to expand the concentration of duplexes to sixplexes, stacked apartments, and the like.

These bills aren’t only a way to address population density and housing in Washington; they will protect the environment as well. ADUs support sustainable development plans as they typically require fewer resources during construction, are energy-efficient, and minimize urban sprawl.

ADUs and resource efficiency

Building a new home is a resource-intensive process with high carbon costs. Newly built homes create 50 million tons of carbon per year in the U.S. alone, which is an obstacle to achieving state and national climate action goals that have been set.

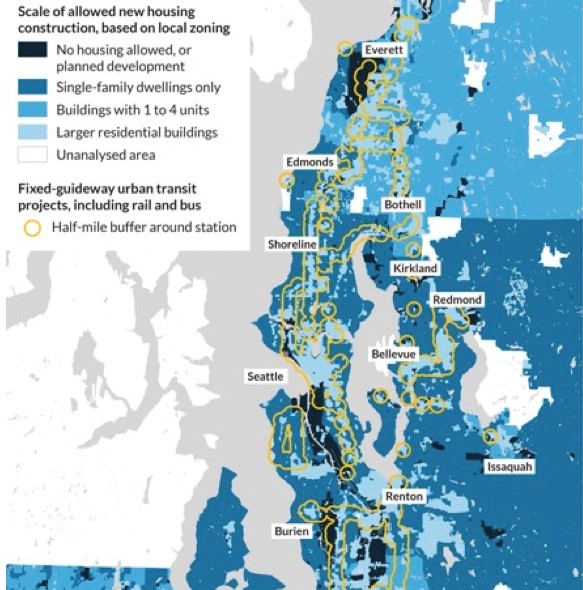

ADUs in cities can help cut back on carbon emissions in several ways. In Washington, transportation emissions are a huge culprit because many, especially suburban and rural residents, have long commutes for work and errands. When it comes to emissions from suburban homes versus urban homes, people who live in suburbia are responsible for more transportation emissions than city dwellers. Building affordable ADUs in cities allows people to live closer to employers, cultural attractions, amenities, and public transit.

ADUs that serve as small homes have the potential to dramatically reduce carbon emissions and improve energy efficiency. This claim is backed by state-sponsored research completed in neighboring Oregon, which found that extra-small homes produce 20% to 40% less construction emissions than medium standard homes per year. ADUs also lower heating and cooling costs than larger homes, and, in urban settings, fewer transportation emissions than comparable homes built farther into suburbs.

However, rural DADUs may not have the associated benefit of reducing transportation emissions as compared to urban infill housing. And they don’t have the same water-saving properties as urban ADUs. This is a serious issue in the Evergreen State, which experiences high levels of water stress.

Homeowners who do decide to convert existing structures into ADUs can also use the funds they generate from rent or guest accommodation to fund energy-efficient installations like solar panels. Solar panels offer long-term savings and increase the resale value of a home. Some homeowners may be eligible for federal solar credits, one-time rebates, and low-interest loans.

ADUs, which tend to be smaller than most homes, are perfect candidates for electric heat pumps. New rules, which come into place in March 2024, make it easier for homeowners to install energy-efficient heat pumps. This would aid in making ADUs even more sustainable, as heat pumps produce less pollution than gas furnaces. Homes that utilize heat pumps, which run solely on electricity, embolden efforts to move away from gas heating and lend support to calls for a greener grid.

Challenges facing ADUs

Despite legislative changes designed to make building ADUs easier, to increase urban infill development, and to help city-dwelling Washingtonians live more energy-efficient lives, ADUs still face some serious hurdles before they become the norm across the state. Parking requirements, in particular, are one of the most serious impediments to ADUs. For example, if an ADU is planned more than a half mile from a major transit stop, a Washington city or county may cite off-street parking requirements as a reason to withhold permitting for the project. There are challenges to ADUs in less densely populated areas, too. This spring, lawmakers battled over rural ADUs and whether they are aligned with the state’s housing and environmental protection goals.

Washington’s lawmakers and citizens are rightfully concerned about urban sprawl. Urban sprawl, which occurs when a town or city starts to creep into rural land, is a major issue for the environment on multiple fronts. Not only does it turn green spaces into city-like zones, but it also infringes on farms and undermines our ability to support resilient, regenerative food systems.

Allowing more housing in already built-up areas is key to slowing sprawl. Dr. Mitch Hunter, Senior Research Fellow with the American Farmland Trust, explains that a metropolis is “like an accordion,” and that building denser suburbs is akin to squeezing an accordion. Building and converting more existing structures into ADUs helps urban areas reduce sprawl, but denser multifamily housing is needed, too.

Lawmakers should also address the potential inequalities that ADUs can fuel, too. Currently, wealthy White homeowners disproportionately benefit from ADUs. This could cause income disparities and entrench racial inequalities if left unchecked. Natalie Bicknell Argerious notes that this is largely due to income inequality and the fact that White households “are significantly more likely to live in a single-family home than households of color.” Clearly, much must be done if the state is to meet its affordability, equity, and sustainability goals.

Legislative moves that promote ADUs can free up funds for residents who choose to convert existing structures. Converted garages add plenty of value to a home in the form of rental space and guest accommodation. This is key, as eco-friendly home modifications to improve energy efficiency can be costly. By raising funds through rent and guest accommodation, folks can justify the investment in solar panels, heating pumps, and more energy-efficient HVAC systems.

Scaling urban ADUs

Of chief concern is the number of ADUs that Washingtonians can and will build in urban areas. For these structures to be most effective, it’s best for them to exist in cities where they will not contribute to sprawl and will add housing for those who need it.

MRSC reports that Growth Management Act (GMA) counties, which must plan according to Washington’s GMA statutes, are required to allow two ADUs per qualifying lot. A total of 28 counties, making up 95% of Washington’s population, are GMA counties, which places cities like Seattle, Spokane, Tacoma, and Olympia within the ADU provisions.

There’s huge potential for ADUs to scale up, given that local authorities can’t limit the units’ size to less than 1,000 square feet. According to the Cato Institute, ADU construction increased by 253% from 2019 to 2022 in Seattle alone, outpacing the production of single-family homes. However, the actual numbers might seem like a drop in the bucket.

In 2022, the city issued 988 ADU building permits, while Seattle’s greater metro area saw 2,254 ADU applications. This might not seem like a lot, but Axios reports that the growth rate per capita for Seattle’s ADUs is more than two times faster than it is in any metro in California, where about 16% of new builds are ADUs. Overall, Seattle permitted about 8,200 homes in 2022.

Conclusion

ADUs offer cost-effective living for residents in urban areas. They’re also great for the environment, as smaller spaces reduce urban sprawl, are less energy intensive, and have significantly lower carbon costs during the construction process. Residents who do decide to build ADUs can further reduce their footprint by utilizing energy-efficient heat pumps and installing solar panels.

What remains to be seen in 2024 is whether ADUs will be able to put a real dent in the housing crisis. It’s not unreasonable to gather that ADU construction will continue to increase, and every little bit helps. However, cities can’t rely on ADUs alone to solve a housing problem that requires large-scale investment and a concerted effort from federal, state, and local governments to encourage homebuilding in the private, nonprofit, and public sectors.