The $1.45 billion transportation levy proposed by Mayor Bruce Harrell’s administration only promises to add around 10 miles of new protected bike lanes to the city’s arterial streets, representing a big step back from the ambitious goals of the Levy to Move Seattle, expiring at the end of the year. The levy is currently being scrutinized by the Seattle City Council, which is set to add amendments and approve the entire package, sending it to voters, by early July.

When the proposal was first released in early April, The Urbanist noted the lack of a specific goal around adding new separated bike infrastructure to city streets. Instead, levy materials promised to build five new neighborhood greenways and upgrade 30% of the city’s existing protected bike lanes, in an expansion of its “better bike barrier” pilot program. SDOT chose to emphasize that expansion of the network was focused on connecting gaps in the network — an additional $20 million added to the package between April and May was intended to add more new facilities in South Seattle, which has been underinvested in relative to the rest of the city when it comes to bike infrastructure.

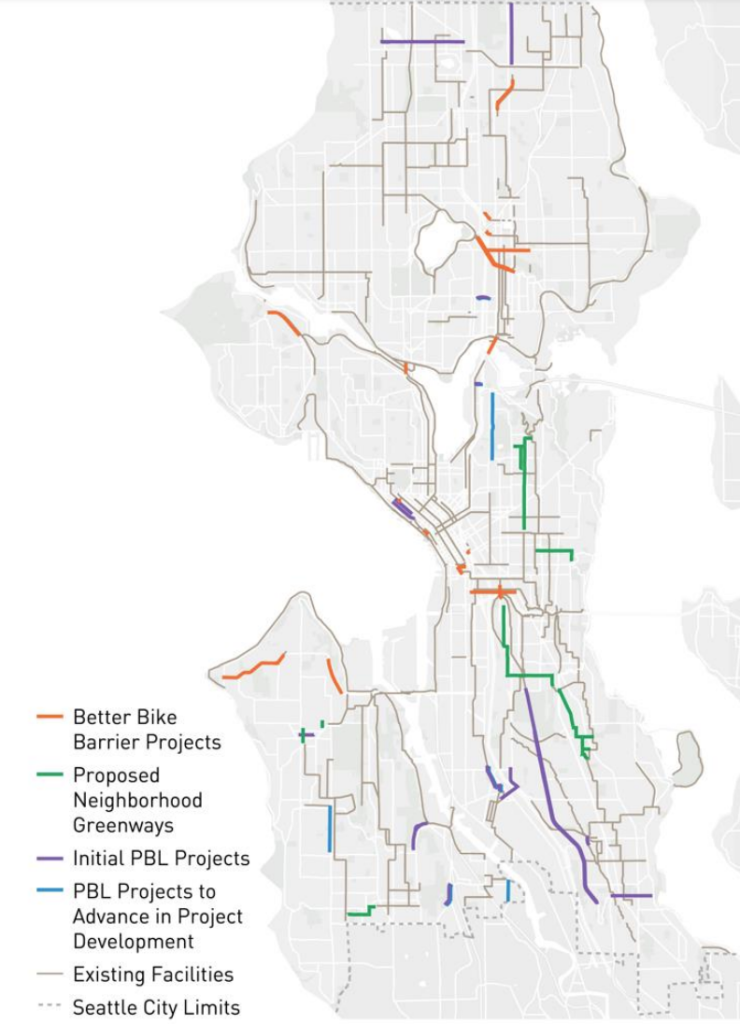

However, a map presented to the city council earlier this month revealed specific streets that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) would upgrade given the proposed $68 million in funding over eight years, part of the larger $114 million bike safety budget. It only includes 14 new projects, adding up to just over 10 miles of new facilities, depending on exactly where project boundaries end up falling.

Purple lines indicating protected bike lane projects on the map are absent from entire swaths of the city, with just one each in District 3, 4, and 7, and no projects at all in District 6. Would this really be all that a $1.45 billion levy, the last renewal of Seattle’s single-biggest source of transportation funding ahead of the city’s longstanding 2030 climate and safety deadlines, is set to deliver?

SDOT’s Climate Change Response Framework, an addendum to the massive Seattle Transportation Plan that the City Council adopted earlier this year, calls for the share of trips made by walking, biking, and rolling to increase from 23% to 31% by 2030.

The proposed projects do seem to prioritize small upgrades to segments of roadway that are some of the most harrowing and frustrating stretches for people trying to get around the city by bike, particularly in the South End. But even as the city notes a desire to fill in network gaps using levy funding, the plan also leaves a lot of gaps unfilled and doesn’t seem to represent a bold vision for providing access to the city’s bike network to more residents.

SDOT spokesperson Ethan Bergerson confirmed that these projects are the full extent of what the city expects to be built using dedicated levy funding, with additional projects dependent on finding additional dollars.

“The bike project map we presented to Seattle City Council highlights the currently identified bicycle projects in the transportation levy proposal,” Bergerson said. “Using the Seattle Transportation Plan as a guide, there would still be the possibility of building more potential bicycle projects over the eight years of the renewed levy as funding is identified, grants are received, or through the Complete Streets process.”

By contrast, the Levy to Move Seattle included a promise to build 50 miles of on-street bikeways along with 60 miles of neighborhood greenways. That commitment assumed that new facilities could be implemented at lower cost than they ultimately achieved, and levy funding was exhausted long before getting anywhere near that goal. But because the commitment had been made, SDOT worked to find additional resources to add more miles, and without that commitment, entire projects that are currently in the pipeline, including the Georgetown to Downtown Safety Project, and the Alaskan Way bike lane in Belltown, likely wouldn’t be happening at all.

In the end, Move Seattle’s legacy will be more than 40 miles of new protected bike lanes. The next levy seems to rest of the laurels of this achievement. Rather than continuing the formula of using ambitious goals to mobilize resources to drive a significant expansion, City policymakers appear to have concluded that goals shouldn’t be quite so ambitious next time.

Them: can you believe the new Move Seattle Levy doesn't address The Missing Link, even though it's planning for the next 8 years of bicycle infrastructure?

— Ace The Architect (@andrew_ace_agh) May 21, 2024

Me: which missing link?

cc: @seabikeblog @sngreenways @seattledot #Seattle #cycling #bikeSEA pic.twitter.com/Fk3wp54HYt

Without any overall vision or concrete bike network goal for 2032 when the levy expires, that impetus to push for additional projects likely won’t exist. This may be the point for hesitant politicians who would rather focus resources elsewhere. In contrast with Move Seattle, this levy seems to prioritize making investments in projects that have already been built, a fact that means fewer political fights over creating space for bike lanes.

The limited list of “initial” protected bike lanes included on the map includes:

- N 130th Street connecting the planned light rail station with the Interurban Trail.

- 15th Avenue NE between NE 125th Street and the city limit at NE 145th Street.

- An I-5 overcrossing at NE 50th Street between the U District and Wallingford. Basically nothing is known about what this would look like, and it comes on the heels of a promise to upgrade the overpass at 45th Street in Move Seattle, which didn’t materialize.

- A small connector between Eastlake Avenue E’s protected bike lanes, being installed as part of the RapidRide J project, and a multi-use path over I-5 at Roanoke Street planned as part of the final phase of the SR 520 bridge replacement project. Connection to Harvard Avenue E probably not included.

- Upgrades to existing paint bike lanes along Elliott Avenue and Western Avenue in Belltown south of Broad Street, as part of a planned repaving project.

- Phases two and three of the Beacon Hill bike route, from Spokane Street south all the way to the street’s terminus at 39th Avenue S.

- Airport Way S through the Georgetown business district, connecting the Georgetown to Downtown project starting construction this year with the planned Georgetown to South Park Trail — this is likely to be the most contentious project on the list when it comes to parking removal.

- An I-5 connection along S Albro Street between Georgetown and Beacon Hill, connecting with Cleveland High School.

- A connection to the Duwamish Trail via Highland Park Way in West Seattle. This project is already starting to generate some pushback.

- A protected bike lane on Olson Place SW near the daunting highway interchange. It’s unclear what this would actually connect to.

- A small stretch of protected bike lane along SW Alaska Street around Alaska Junction. This is one element of SDOT’s work to plan for the West Seattle Link Extension project.

The map also includes a number of planning projects “to advance in project development” that include:

- 10th Avenue E in North Capitol Hill, connecting to the planned Roanoke Lid and future extension of the 520 trail. Not shown as included is a stretch of Broadway north of where the current two-way bike lane ends at Denny Way.

- A connection along 14th Avenue S in South Park, which would finally connect the Duwamish Trail, the Georgetown to South Park Trail, and King County’s Green River trail.

- A stretch of 35th Avenue SW between SW Morgan Street and SW Holden Street, a spot where the city has already implemented safety-oriented changes but hasn’t previously proposed implementing safe places to bike.

The next public hearing on the proposed transportation levy is scheduled for Tuesday, June 4, at 4:30pm.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.