A new park for Tacoma presents a new opportunity to reconnect the city and its waterfront by removing I-705.

Melanie Jan LaPlant Dressel Park (Melanie’s Park for short) opened on April 11, 2024. It’s a beautiful park, honoring a local leader, featuring views of Mount Rainier, and displaying vital links between the land and the Puyallup people. These aspects, however, remain far away from the rest of the city. An elevated, wide ribbon of concrete — a roaring freeway — separates the park from its users.

Located in the Foss Waterway and near the base of the 11th Street Bridge, Tacoma’s newest park joins Dune Peninsula Park in reminding us that the city continues to do good work when it comes to remediating contaminated former Superfund sites for public and community use.

Like Dune Peninsula, Melanie’s Park also features a smokestack, mixing the site’s industrial past with play. The park features views of the port, the marina, and Mount Rainier. A pavilion and seating accommodate small events and casual eating.

The cultural significance of the land and the water at and near the park to the Puyallup people are foregrounded through interpretive signs and Coast Salish basket weaving motifs. Aspects and features are labeled in Lushootseed, the Coast Salish language spoken in the area since time immemorial.

The park’s namesake, Melanie Jan LaPlant Dressel, a founder of Columbia Bank and community booster, is commemorated through a plaque at the park’s entrance.

Melanie’s Park and Dune Peninsula Park are also linked in another way: neither is particularly accessible. In design, the space between downtown and the waterfront tells you that a car is the best way to close the gap between downtown and the waterfront, meaning that even though Dune Peninsula is geographically more distant from downtown, in experience Melanie’s Park seems farther away.

Once you manage the crossing and arrive at Dock Street, the main road running along this part of the Foss Waterway, you have few options to get across the road to the park; Dock Street has few pedestrian crosswalks along its route.

To connect it and the Foss Waterway to the rest of the city, we ought to remove I-705, which would present Tacoma with options to reconnect the waterfront and its growing list of amenities with the rest of the city. It also presents us with options for expanding the limited success in public space allocation we find down the road, along Ruston Way.

Imagine a green belt that runs from the Glass Museum all the way to Point Defiance, an uninterrupted pedestrian-focused experience characterized by wide sidewalks, biking infrastructure, and regular parks and open spaces—an expanded Ruston Way.

To get there, we have to remove the barrier that is I-705.

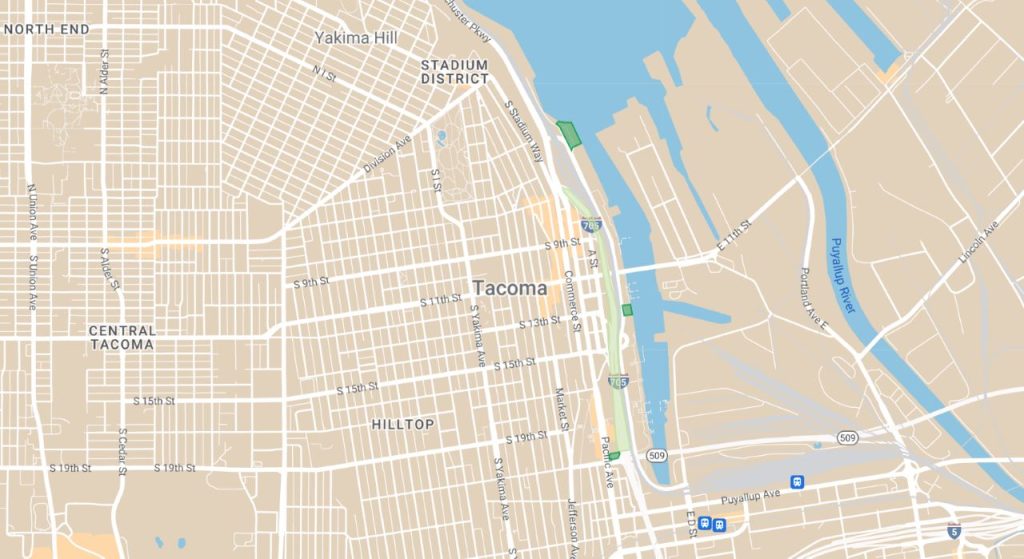

Interstate 705, the shortest highway in the State of Washington, was completed in 1988. Its primary purpose is to get people from I-5 directly to Stadium District, Old Town, and Point Ruston. In effect, I-705 is a remnant of Tacoma’s past when Tacoma — and downtown Tacoma in particular — were something to pass through and avoid.

That version of Tacoma is no longer current. Today, Tacoma boasts a beautiful downtown that is anchored by the University of Washington’s Tacoma campus on one end, and an active and thriving commercial end on the other. Downtown Tacoma no longer needs to hide itself; it does not need to hurry people along to other equally desirable locations within the city as it does through I-705.

Tacoma’s I-705 is one clear example of how highways in the U.S. have cut through cities in ways that dismantle and unmake connection and community. The way I-5 cuts through Tacoma, splitting South Tacoma from the rest of the city, is another example. Many cities only boast a single instance of this type of destructive infrastructure; we have two.

New vitality in cities, together with a recognition that public infrastructure has often been weaponized against people living in poverty and racial minorities, have given us reasons to take down highways in order to make cities whole again. Seattle did this with the Alaskan Way Viaduct, and Seattle, like other U.S. cities, is experimenting with removing highways, or at least capping them with more and better crossings and urban park amenities.

Waterfront highways make natural candidates because they can unlock waterfront park spaces, amenities, and real estate. That’s what Seattle did with tearing down the Alaskan Way Viaduct and what San Francisco did in removing its Embarcadero viaduct.

Tacoma ought to do the same with regards to I-705. It is time to reconnect the Foss Waterway and the Port of Tacoma to the rest of the city. This would link people to Melanie’s Park, Thea’s Landing, and to the handful of restoration sites that exist within the port. Soon, Tacoma will have a maritime-focused high school in in the port. As long as I-705 stands, these sites and places will remain a world apart.

Though much of Ruston Way is for cars, on warm, bright days Ruston Way is filled with people: pedestrians, joggers, dog-walkers, cyclists, and people sitting about. What recommends this part of the city to people is the succession of true public spaces lining the right of way: parks, public art, a pier, and shaded areas with seating.

When we remove I-705 we could extend the success of Ruston Way to Dock Street. Then, this entire waterfront road could be remade into something like an avenida or paseo. Avenidas like those found in Mexican cities such as Mexico City and Guadalajara reference avenidas in Spain and Portugal, and the grand boulevards in France. Our version would allow for low volumes of slow moving traffic (or only transit), but otherwise dedicate a wide median and wide sidewalks to pedestrians, public spaces, and public art.

In Mexico and Europe, these avenidas teem with public life at all times of day. This level and quality of public life is possible in Tacoma too, if Ruston Way is any indication.

Tacoma has a unique opportunity to remake its waterfront into a world-class collection of public spaces that people want to be in. We are making progress on this front — but it is not enough to simply add more parks; we must also connect these parks to each other and to the rest of the city.

Melanie’s Park arrives to remind us that what is standing in the way of this vision is a highway.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.