Metro is struggling to recruit and train bus drivers and rebound above pre-pandemic service levels.

The nationwide bus operator shortage and service crisis continues to linger at King County Metro. Even to provide service at reduced frequencies, the agency is heavily relying on overtime, which is contributing to an environment where drivers are feeling strained, and, if it persists, it could jeopardize the agency’s ability to expand service moving forward.

Addressing the national shortage means approaching the problem holistically, as there is no single cause of or solution to the problem. While King County Metro has taken the vital step of increasing driver compensation in collaboration with the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 587, issues with safety, support, and scheduling remain.

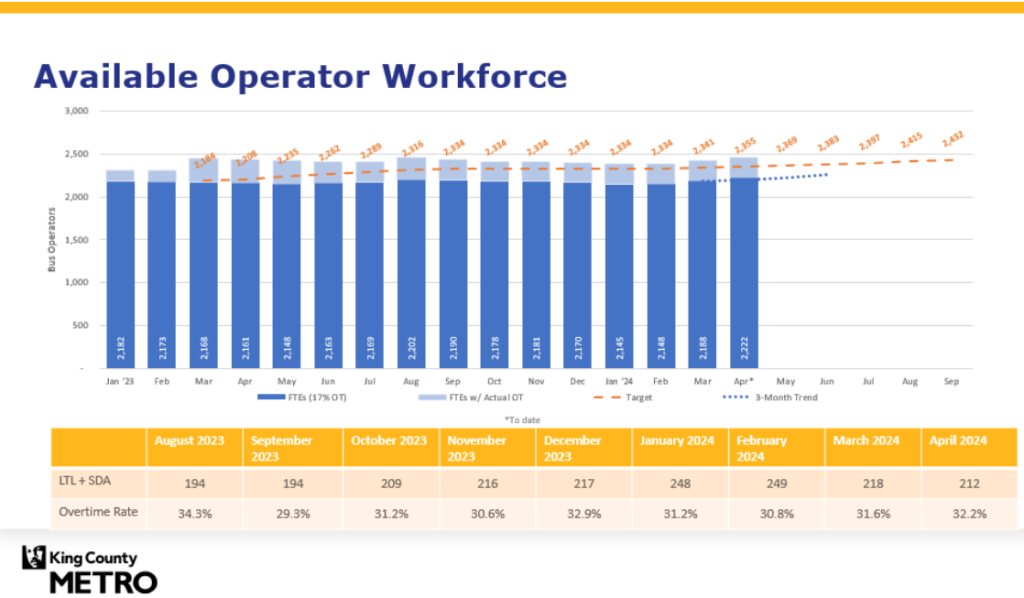

A major consequence of the shortage of transit operators at King County Metro has been an overreliance on overtime. The agency has been using overtime to fill between 30% and 34% of its service hours for the past nine months, nearly double its target of 17%. This issue is compounded by an even more strained training capacity, Metro spokesperson Al Sanders said.

“On any given weekend, when our trainers go out on the road with our trainees, roughly half of the instructors are working overtime and despite this overtime we were short staffed five out of nine weekends,” Sanders said. “This approach is not sustainable in the long term.”

King County Metro has a total bus operator workforce of 2,485. Of those, 1,995 are full-time and 490 are part-time. However, roughly 220 (~8.9%) are on long-term leave or special assignments during any given month. The agency has set an April’s target of a workforce at 2,355 full time equivalents (FTEs) and a fall target of 2,432 FTEs, but due to the leave and special assignments, it’s only achieving those targets through extra overtime and part-time drivers.

It’s not all doom and gloom though: King County Metro has taken the important step of offering higher salaries, retention bonuses, and recruitment incentives of $3,000 to entice people into the profession. This has caused 1,200 people to apply for operator positions since last August, Sanders said. With so many trainers working overtime, the recruiting bottleneck, Sanders said, is at the training phase, rather than with the hiring process.

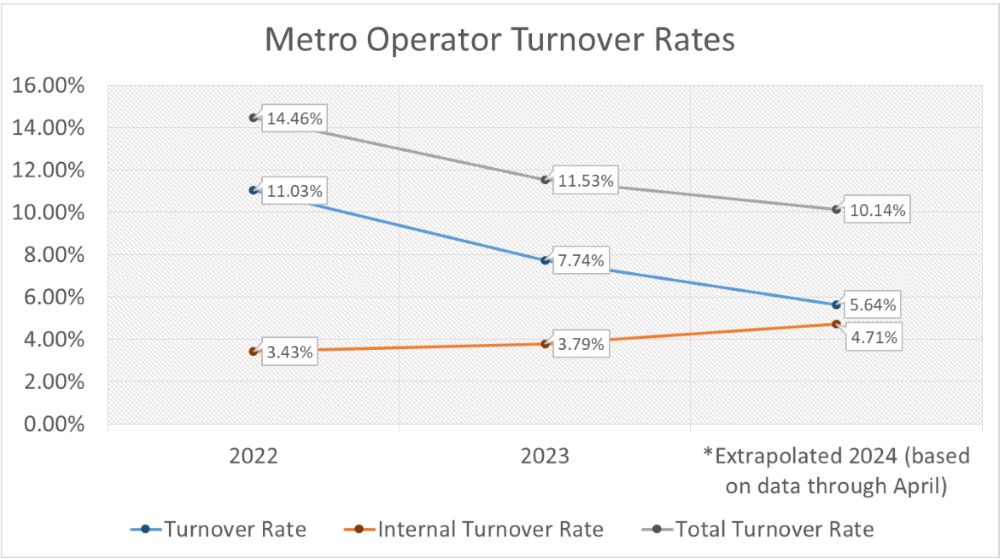

The constructive relationship between King County Metro and the ATU may also be contributing to decreasing labor turnover, as the total turnover rate fell from 14.46% in 2022 to 11.53% in 2023 and continues to trend down in 2024. Lower turnover gives the agency a greater chance to hire enough to increase Metro’s service capacity rather than simply treading water, but the trend would need to hold.

Metro’s inability to find enough qualified trainers to develop expertise in its new hires hints at some of the deeper issues with the bus driving profession which can’t always be addressed by increased pay and benefits, as Transit Center noted in its 2022 report on the national crisis.

Other positive news in the area of Metro operator hiring: 3.5 times more bus operators have graduated operator training this year than had at this point last year. The agency currently has more active operators than any point since December of 2022.

— Ryan Packer (@typewriteralley) April 17, 2024

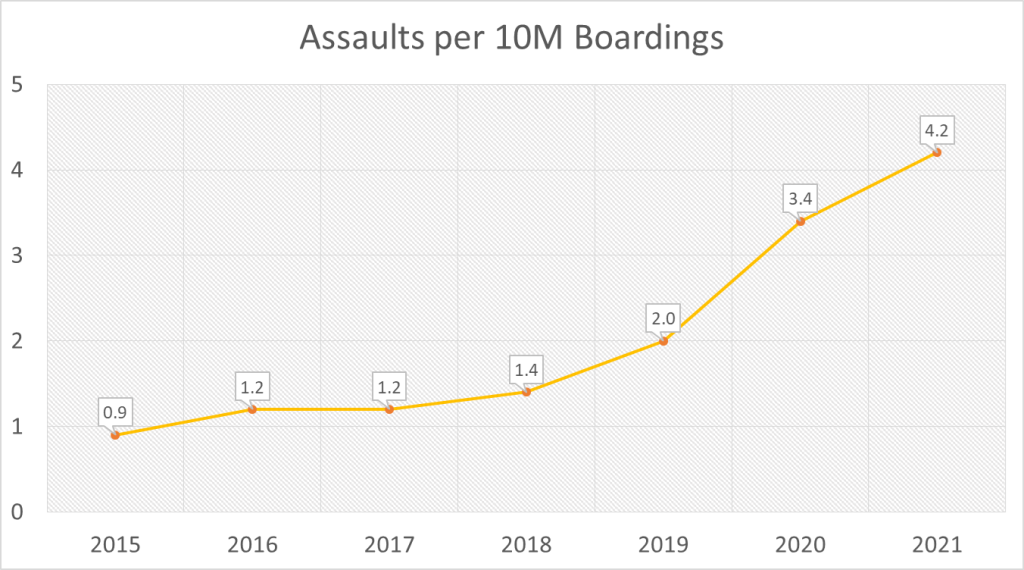

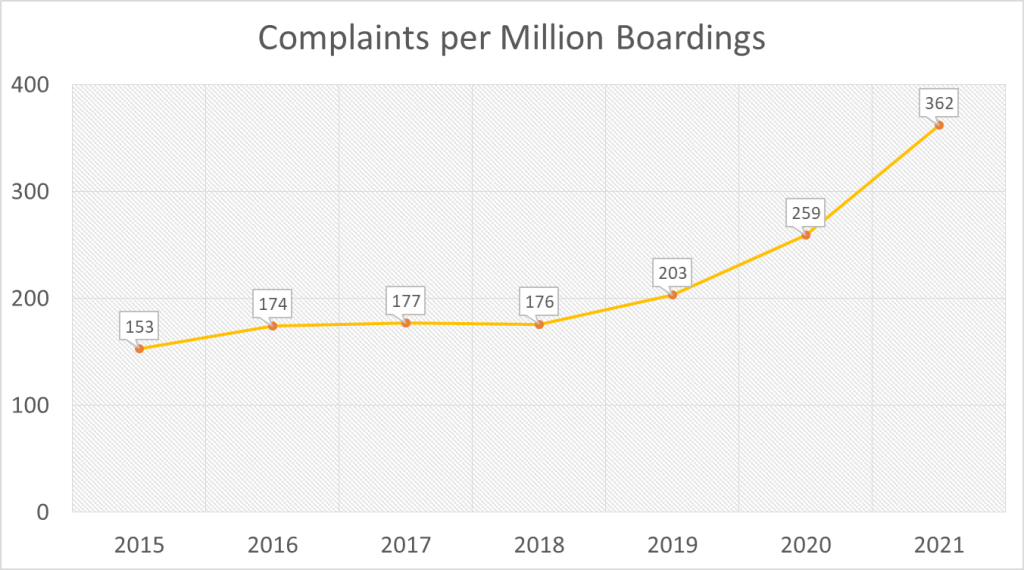

I interviewed six Metro bus drivers, and all expressed similar concerns focused around three main issues: safety, new hires rushed into full-time service, and a job that’s significantly more stressful and dangerous than pre-pandemic driving.

The drivers declined to be identified for fear of repercussions.

One driver, a veteran of more than a decade, said they’d used to invite their partner to ride along during their shifts, but now warns them against using the bus altogether given the current safety situation, especially for women.

Another even more senior veteran said they would not drive any route after 7:00 at night, while acknowledging this means new hires are forced into the least desirable positions immediately, due to seniority rules in route choices.

“We’re not allowed to do drugs, but [passengers] can blow fent in my face.” Another decade-plus veteran driver said in reference to a perceived double standard in the agency’s strict drug testing that prevents drivers from using marijuana off the clock, but its failure to do enough to combat the crisis around fentanyl [fent] and other opioids.

Metro has pointed to a University of Washington study conducted in 2023 (which it helped fund) on fentanyl and methamphetamine exposure on public transportation that found no direct health risk from secondhand exposure on buses. Researchers did find trace amounts of fentanyl in 20% of air samples on buses and methamphetamine in 100%. Only 1 out of 78 samples exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s guideline for occupational fentanyl exposure. However, the authors noted the long-term health risk of daily low-level exposure are not well studied and recommended physical upgrades to filtration infrastructure on buses, which Metro is working to implement, and mental health support to operators.

“The potential for long-term physical or mental health effects related to low-level, daily secondhand exposure to fentanyl and methamphetamine should also be considered for transit operators, who spend 40+ hours each week on the bus or train,” the report noted. “Long-term health effects related to daily secondhand exposure to these substances are not established. In the absence of data relating the amount of these substances found in the air or on surfaces to human health outcomes, protective measures are prudent to keep operators safe. UW researchers recommend using protective measures to reduce exposure to these substances to the lowest level that is reasonably achievable.”

Beyond exposure to drugs, all the drivers who spoke to me expressed feelings of helplessness when witnessing theft, harassment, or even violence occur on their vehicles. They said they thought that more transit security officers would alleviate the majority of the issues, and most voiced frustration over the time it takes for transit police to respond.

Speaking to my own experience, the only time I’ve been the victim of a crime on public transportation was when someone stole my glasses off my face while taking the Rapid Ride H in West Seattle. Fortunately, the assailant threw the glasses to the ground when I sprinted off the bus to chase them down, but these types of incidents do not encourage transit use.

Beyond occasional chaos on the bus contributing to the stress of driving, the operators I’d interviewed emphasized the importance of training, as did Metro’s spokesperson. One difference that emerged was that the six drivers interviewed do not believe faster promotions to full-time is a solution to the shortage. Every driver who spoke to me said in this working climate — more erratic motorists on the road and more anti-social behavior on the bus — new hires need time to ease into the position.

According to the experienced drivers, the norm used to be two to five years of part-time driving before advancing to full-time, permitting operators to gain and solidify skills gradually before being thrown into full-time shifts. Now they say the norm is about six months, sometimes going as low as three.

While advancing drivers from part-time to full-time is inevitable and not necessarily an issue with proper training and mentorship, a shortage of training staff can jeopardize instruction. Staffing up in Metro’s training team could help ease that pinch point while ensuring new hires get the support they need. Metro plans to shift 220 current part-time drivers to full-time in the coming months, Sanders said, which has the veterans I spoke to a bit worried.

At the same time most veterans acknowledged new hires need to make a living, and most lamented the cost of living making the restriction to part-time work for new employees difficult to swallow. The prospect of a good-paying full-time job is what attracts many to the profession and helps retain them in spite of occasionally stressful conditions.

The drivers I interviewed agreed that an increased presence of transit safety officers would go a long way in alleviating the stress of the job and improving the atmosphere of safety on the bus. Metro’s current contingent is composed of 160 transit security officers and the agency plans to hire an additional 10 members, according to Metro spokesperson Al Sanders. Drivers said a proactive security presence would best improve the situation, as it’s best to avoid a situation where police need to be called altogether: “Just have somebody who makes you think twice before deciding to do something you shouldn’t” as one driver put it.

Based on the bottlenecks in training and hiring, King County residents shouldn’t necessarily expect an expansion of bus service anytime soon unless there are improvements in training capacity and the workplace environment for drivers, which means addressing safety issues and working to establish a sense of security rather than a climate of fear in a space meant to be open and accessible to all. Failing to address those spheres could mean the labor shortage and associated service cuts linger.

This article was updated on May 20 with labor turnover data.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.