At least 20 schools are on the chopping block, despite this offering no solution to the district’s budget crisis.

Last week, the Seattle school board voted to proceed with a plan that could close 20 or more public schools across the city. The “well-resourced schools” plan presented by Superintendent Brent Jones would be the largest change to Seattle Public Schools (SPS) in over four decades.

Based on the experience of other cities with mass school closures, SPS’s plan would also worsen the district’s budget woes, worsen student learning outcomes, cause further enrollment decline, and exacerbate inequities. It could also dissuade families from moving to or staying in Seattle, undermining efforts to add missing middle housing and grow Seattle’s population.

The SPS closure plan

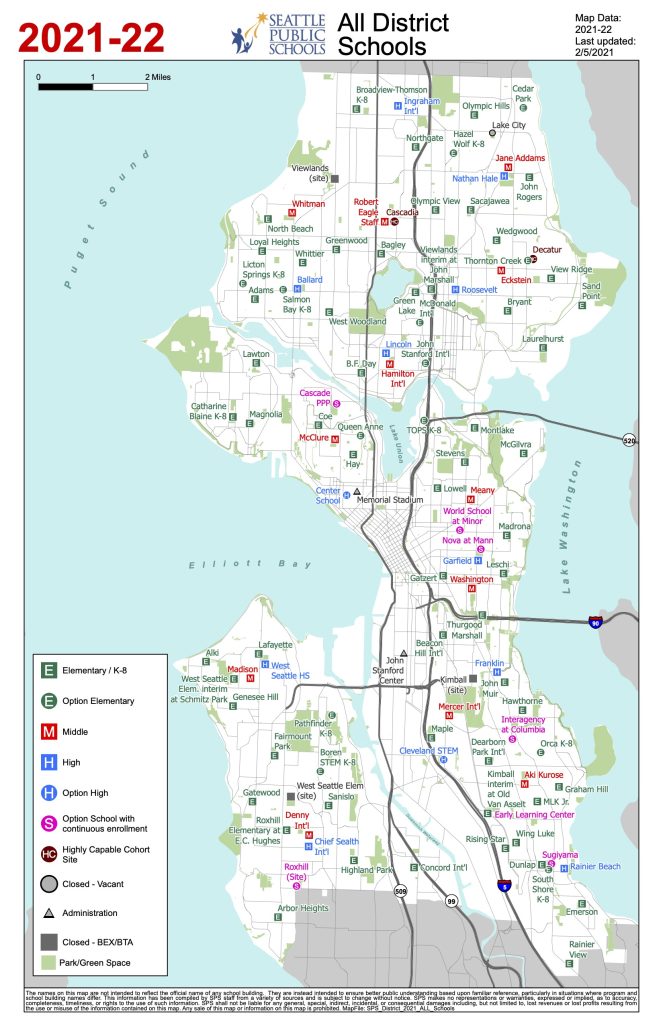

SPS proposes to reduce the number of schools serving kindergarten through fifth grade (K-5) students from more than 70 to about 50. These schools would be evenly distributed, with about 10 per region. (SPS divides itself into five “regions” – Northwest, Northeast, Central, Southwest, and Southeast.) The district would close not only K-5 neighborhood elementary schools, they could also close K-8 option schools as well.

Notably, this is not a plan to simply close the smallest schools with the lowest enrollment. SPS leaders have consistently said that the schools which close may not be the smallest ones. The district has yet to share any objective criteria by which they will determine which schools they wish to close, and have not given any indication they plan to involve the public in the process of identifying which schools to close.

Nor is this a plan driven primarily by a desire to save money. SPS leaders have also consistently said they would want to close schools even in the absence of a budget deficit. Superintendent Jones also said in 2023 that closing schools would not provide immediate budget savings and that savings may not materialize for two to five years. In a recent podcast interview with KUOW, school board president Liza Rankin also acknowledged that their closure plan might not save money. Since the majority of SPS’s spending is on staff, savings would only come through mass teacher layoffs.

As a result, we do not know precisely why district leaders want to close 20 or more schools. But they are determined to proceed.

The district has also not explained what it would do with the closed buildings. Under state law, if a public school district closes a school, and they put it up for lease or sale, charter schools have the right of first refusal to rent or buy that building. Unless SPS plans to leave 20 school buildings closed and gathering dust, this plan could initiate the privatization of nearly two dozen public schools.

At no point has SPS asked the public whether it wants to close schools. In fact, district leaders appear to be deliberately avoiding it. A series of community meetings held in summer 2023 asked participants to share what they considered important and valuable about their schools – but specifically avoided asking whether those schools should close.

The “well-resourced school” plan was then railroaded through at last week’s board meeting. It was presented to the board as an “introduction and action” item, meaning that it was shown to the board and then the board was asked to approve it at the same meeting.

This would be like the City of Seattle presenting a new transportation plan to the City Council, and then asking them to approve the plan at the same meeting, but without any financial analysis or details like bike routes, sidewalk construction, or which transit services would receive upgrades.

Unfortunately, after asking only a few cursory questions, the school board rubber stamped the closure plan despite vocal public opposition. This vote does not commit SPS to closing specific schools. District leaders have said they will share a list of schools they wish to close in June, and the board would take a final vote to close them in fall 2024.

Missing details

Research on mass school closures in other cities has clearly demonstrated that such closures hurt student learning, exacerbate budget deficits, worsen enrollment declines, and increase inequities.

Despite these facts, SPS has not shared any details to bolster their case for closing schools. Nor have they shared any analysis that would show how Seattle could avoid the poor outcomes school closures have caused in other cities.

SPS has not shared any financial details showing the costs of closing 20 or more schools, the savings that closures could generate, or when those savings would materialize. As a result, the public is unable to determine whether the closure plan is financially sound.

Nor has SPS properly analyzed why its enrollment has declined. The state legislature ordered the district to conduct a study on why families have left the district, and appropriated $100,000 to fund it. SPS is proceeding with its plans without having received the results of that study.

Research has shown that students learn better in schools with smaller enrollment. SPS has not shown any analysis on how sending students to schools with larger enrollment would impact their learning or their well-being.

Missing alignment

The district’s school closure plan does not appear to be aligned in any way with Seattle’s upcoming comprehensive plan update. The comprehensive plan expects a city with a population of 1 million by 2050, and plans for at least 100,000 new homes to be built over the next 20 years. Many critics believe that target is too low and that the comprehensive plan should facilitate the construction of more homes more quickly.

The new comprehensive plan, in concert with recent state legislation designed to facilitate the construction of more homes affordable to and capable of housing working-class and middle-class families – often described as the “missing middle” – should bring more families with school-age children into Seattle beginning in this decade.

SPS’s plan, and its enrollment projections, do not appear to include or anticipate any of these changes. The district simply assumes enrollment will continue to trend downward, despite the likelihood of significant new housing supply being added to Seattle in the near future. If the district closes 20 schools, they may quickly find themselves in the same situation they did 15 years ago when they had to reopen schools they had just closed, at great cost to their budget and to student well-being.

Worse, the district could wind up discouraging that new housing from being built, and turning away prospective families who might want to live in Seattle, through a mass closure of public schools. Closing schools, especially without the consent of the public, will show a lack of trust and faith in the public on the part of the district. It will indicate to families that they should look elsewhere to get their kids educated – and that will cause them to move to the suburbs, which will also be building missing middle housing to welcome these families. This suburban exodus has happened before in Seattle, and is a common feature of life in other metropolitan areas in the U.S.

The district’s closure plan also does not appear to align with the specific locations where new housing will be built. Under the current draft of the comprehensive plan, urban villages may become school deserts and not be served by a neighborhood public school. For example, if the district were to close Adams Elementary School, whose enrollment has declined since the onset of the pandemic, there would not be a public elementary school within a mile of the center of Ballard, even as the “Ballard Hub Urban Village” is upgraded to a “Regional Center” in the plan, which will encourage even more growth.

Similarly, the district does not appear to have taken into consideration the city’s transportation plan. Closing neighborhood schools that are walkable for families and making students go to a school that is further away ensures more kids will be driven to school, especially if the state legislature continues to refuse to fully fund school bus service.

Research also suggests that a longer school commute hurts student well-being. It certainly would take Seattle farther from its 15-minute city aspirations, in which residents can meet their basic needs in a 15-minute walk from home.

More housing won’t solve this by itself

Since the announcement of SPS’s school closure plan, many urbanists have responded by pointing out that this is a predictable result of limiting the supply of new housing, and that building more housing will increase enrollment and prevent school closures.

In a general sense this is true. But it may not work out that way here in Seattle. SPS’s crisis may in fact be an early warning sign that state laws and practices are beginning to seriously undermine the ability of cities to provide and maintain basic services and infrastructure, even as its population rises – and that this failure may pose an existential threat to Seattle’s ability to grow.

Seattle’s population soared in the 2010s, going from 610,000 in 2010 to 753,000 in 2019. Seattle did lose some population at the beginning of the pandemic. But it quickly recovered, and with the most recent state estimate from 2023, Seattle has 779,200 residents – still well above its 2010 population.

Despite this growth, and despite a booming Biden-era economy, Seattle’s local governments still face a financial crisis. In addition to the $100 million deficit facing the schools, the City of Seattle faces a deficit of more than $240 million. It’s not just Seattle. Public school districts across Washington State face ongoing deficits, regardless of whether their student populations are rising or falling.

The underlying problem is that the state legislature has limited the ability of local government to raise the revenues needed to provide basic services, and inflation is exacerbating the crisis. In 2007 the state legislature, with Democratic supermajorities, enacted a 1% property tax cap that had previously been approved by voters in a low turnout election in 2001 but was later on thrown out by the courts.

Then, in response to the McCleary decision that required the state to amply fund its public schools as the state constitution requires, the legislature adopted a new education funding plan in 2017 that many school districts, including Seattle, predicted would actually leave them with less money than before. These predictions have come true, particularly as the legislature added an additional property tax limitation, capping the amount of money school districts can raise for their operations through a local levy. The state legislature has since exacerbated this problem by failing to maintain its funding levels to keep pace with inflation. When adjusted for inflation, state funding for public schools in Washington has actually fallen by about $1 billion in recent years.

The result is that Seattle is struggling to provide public schools, libraries, park programs, transit service, and other basic services even as its population grows. We must make it easier to build housing in Seattle. But we cannot expect that doing so will solve local government’s financial woes unless we also remove state limits on the ability of those local governments to raise revenue.

Without those changes at the state level, and without new leadership at the school district that is committed to public education as a universal good that is available to everyone, Seattle may well become a two-tier city. It would be a city in which public education is simply a safety net program for those who are the worst off, and where everyone else is expected to educate their kids by paying out of their own pockets.

The first step to avoiding this outcome is for the public to tell the school board that they do not accept their mass closure plan. Instead, the district must collaborate with the public to develop a range of alternative plans to address the deficit, just as Sound Transit presents alternatives for analyzing a light rail alignment, just as the City of Seattle presented alternatives for the comprehensive plan. These plans must be accompanied by a renewed commitment to bringing every child into the public schools and meeting their needs, rather than pushing them toward private options or the suburbs. Only through that community effort can we save our public schools – and with it, save Seattle’s future ability to grow and thrive.

Robert Cruickshank serves on the board of directors at Paramount Duty, a “non-partisan, grassroots group of parents and allies advocating for Washington to amply fund basic education and fulfill its paramount duty.”

Robert Cruickshank

Robert is the Director of Digital Strategy at California YIMBY and Chair of Sierra Club Seattle. A long time communications and political strategist, he was Senior Communications Advisor to Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn from 2011-2013.