$100 million request would fund about 17 upgrades on state highways lacking bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

In the unincorporated community of Skyway, Martin Luther King Jr Way S is also State Route 900, a four-lane state highway with a 50 mph speed limit to rapidly convey motorists between Seattle and Renton. In spite of the fact that the street is home to a fair number of apartment complexes, a mobile home park, and multiple businesses, MLK is missing pedestrian facilities for most of its length and includes infrequent places to cross, even as King County Metro runs frequent buses up and down the corridor. The street includes no bike facilities, and drivers regularly exceed the posted speed limit along the entire stretch.

It’s exactly streets like MLK that the Washington State Legislature had in mind when it passed a “complete streets” mandate in 2022, requiring the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to assess its state highways for missing bike and pedestrian infrastructure and, where it makes sense, to fill in critical gaps along with any maintenance projects that exceed $500,000 in total cost. To date, WSDOT has screened over 800 highway projects and found Complete Streets elements that are just waiting to be implemented on nearly 300 — over a third of all projects the department has in the pipeline.

But the legislature largely left its new mandate unfunded, especially as overall funding for state highway maintenance remains well below the level needed to keep pace with maintenance needs on the ground. All of the projects that had been heading toward design in 2022, when the new mandate took effect, now have additional costs associated with them for new sidewalks and protected bike lanes, with no corresponding funds within WSDOT’s budget to pay for them. That’s prompted the department to get creative about how to move these urgently needed facilities forward.

As part of the brand new Climate Pollution Reduction Grants (CPRG) program, funded through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), WSDOT is partnering with the Washington Department of Commerce and the Department of Ecology to request a fairly unprecedented amount of funding for projects that have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They are seeking just over $100 million to accelerate the Complete Streets program and get shovels in the ground.

Seventeen separate highway projects would be set to receive funding if the award is successful, improvements to state highways in every corner of the state that would increase walking and biking access to approximately 350,000 people living in close proximity. State highways running through large cities like Bellingham and Vancouver are on the list of planned projects, and also highways running through small towns like Wishram, Morton, and Electric City. Also on the list is SR 900 through Skyway, where a corridor study completed last year produced a number of potential projects that could improve safety on the street, including a 10-foot shared use path along the north side of the street that could finally connect the pedestrian network and provide safe biking access.

The grant wouldn’t fully fund highway maintenance, but would instead cover the extra cost associated with the new bike and pedestrian elements, assumed to be around 40% of the total costs across all of them as a whole.

“Electrification of the transportation system is essential, but not sufficient to meet climate goals, and does not address the need to improve access for the Washingtonians who do not drive,” is how Washington’s grant application frames the urgent need to make these investments in its grant application, submitted this spring.

“Studies have found trips under 3 miles to be more than 50% of all daily trips, which is the active transportation standard for an easily bikeable distance,” the application continues. “Complete streets that enable people of all ages and abilities to walk, cycle, roll, and access transit can transform our transportation system to one where people can freely access their destinations with little to no [greenhouse gas] emissions or co-pollutants, enjoy healthy exercise and connection to their communities, and benefit from improved equity, safety, and quality of life.”

Fixing Washington’s incomplete and dangerous highways also has an immense potential to reduce traffic fatalities and serious injuries from traffic crashes. As the Washington Traffic Safety Commission releases new traffic fatality data for 2023 showing the highest number of lives lost statewide to traffic violence since the 1980s, the potential of Complete Streets improvements to transform highways across the state has no parallel. Close to half of the 810 traffic fatalities last year in Washington were on state highways, with many of the surface-running state highways like SR 7 in Pierce Counties seeing fatality rates well above the state average, a clear byproduct of their design.

Along with the $100.2 million for Complete Streets, this grant request includes funding for a whole array of projects that would cumulatively allow the state to avoid releasing 4.7 million metric tons of carbon by 2050, according to the application. Ferry terminal electrification, replacement of medium and heavy duty vehicles with electric counterparts, waste management, and even the decarbonization of refrigeration systems at local grocery stores would be included in the entire package if EPA were to award the funding. In total, the request amounts to just under $470 million in total, grabbing opportunities for carbon reduction that could be happening at the state level if agencies simply had more funding.

“These are projects that we are mobilized to deliver,” said Celeste Gilman, a strategic policy administrator in WSDOT’s Active Transportation division. “The grant is for a specific time period, 2025 to 2030, and projects can be implemented and the greenhouse gas emissions benefits can be realized, starting within that grant period, but then continuing on an ongoing basis.”

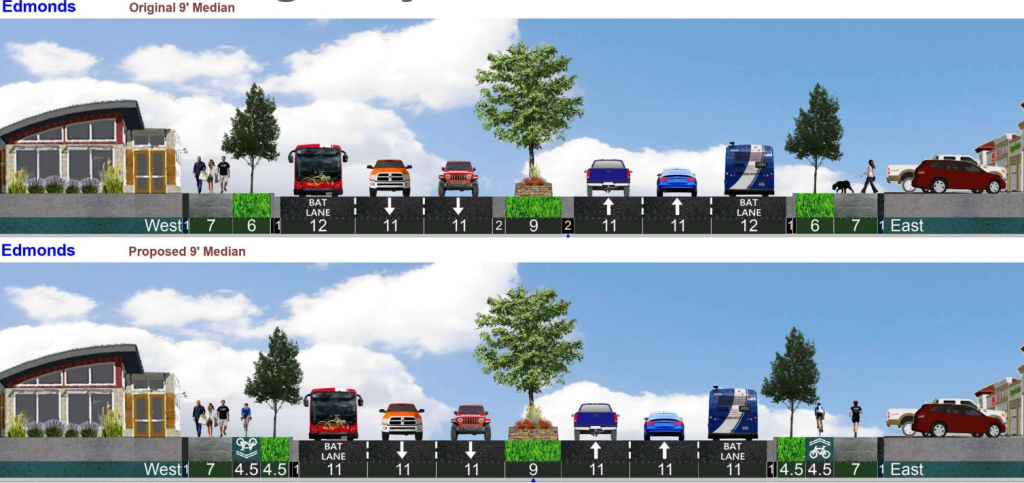

But the Complete Streets funding has the potential to go beyond the urgent need for carbon reduction by moving the needle on safety and improving mobility on a scale that, to date, has been mostly piecemeal and dependent on local jurisdictions taking the lead. By managing Complete Streets at the state level, WSDOT has been able to advance design standards that ensure that if bike facilities move forward, they’ll actually ensure consistent standards across all of the new infrastructure. Those standards are already starting to play out in places like Edmonds, where local funds to improve State Route 99 are meeting the new Complete Streets requirement, prompting changes.

At this stage, WSDOT is not at the point of proposing specific designs for how the highways will get modified.

“We are committed to delivering Complete Streets improvements, we have a lot of incomplete streets across the state,” Gilman said. “We are talking about changes, and what those changes look like needs to be thoughtfully developed with the community. This is their home, this is where they live. And so that takes effort to do that planning work of, what should the future complete street state look like? And there are a variety of solutions: some of them are very low cost, and it’s paint and a few separation elements. And others are more costly, and may involve expanding the right of way.”

Awards as part of the CPRG program are expected this fall. If WSDOT isn’t able to secure funding via this grant, that puts the legislature that much more behind when it comes to fully funding its own Complete Streets mandate. “We deliver Complete Streets improvements when we have projects,” Gilman said. “And if we don’t have a project, because we don’t have funding, we don’t have the opportunity to correct the walking and biking.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.