Just before Seattle City Council held its first hearing on Mayor Bruce Harrell’s $1.45 billion transportation levy proposal on Tuesday, safe streets advocates met on the steps of City Hall, presenting their larger, safety-focused alternative, and rolled out public poll results indicating voters are likely onboard with going bigger.

Seattle’s transportation levy funds about 30% of Seattle’s transportation budget, with the nine-year, $930 million Move Seattle Levy now in its final year, after voters approved it in 2015 by a 58% to 41% margin.

Northwest Progressive Institute (NPI) bundled and commissioned the poll which was conducted by Change Research, with mobility advocacy organizations chipping in on poll costs. At the press conference, Andrew Villeneuve, founder and executive director of NPI, was on hand and noted that fix-it-first and traffic safety investments were very popular with Seattle voters, based on the results.

“We found that people are most supportive of repairing bridges that are in poor condition, followed by repaving streets that are in poor condition,” Villeneuve said. “And then we had safety improvements on most dangerous streets in the city like Rainier Avenue and Aurora and MLK, building sidewalks where they’re missing and investing in Safe Routes to School. Those are the top five priorities.”

NPI partnered with Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, the Sierra Club, the Transit Riders Union, Transportation Choices Coalition, Disability Rights Washington, Lid I‑5, and Sightline Institute to craft the questions and fund the polling. Representatives from these groups said they were heartened to see voters supported a bigger levy. Unlike in the poll that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) commissioned, the NPI poll found that voter support actually increased when the size of the levy increased.

“And we said there’s two possible paths with the council,” Villeneuve said. “One is to raise $1.7 billion by asking voters to authorize an eight-year levy. And the other option we asked out was raising 1.9 billion. Now the reason we asked about these two is because they’re more than what the city has proposed. We wanted to know if that would resonate with voters. Turns out it does.”

By a 54% to 26% margin, respondents preferred the larger $1.9 billion option after they were briefed on what that extra money would fund.

“And just to give you a summary of the differences between options, A and B: option B, we explained would explained would build 180 blocks of more sidewalks, improve the transit experience on two more often-delayed bus routes, implement safety improvements on five more high-crash corridors and complete thousands of additional safety, mobility and maintenance improvements. So those are the main differences between A and B in terms of what that additional several hundred million would get you. So 26% said they’d prefer option A and just the $1.7 billion option. And 54%, which is the majority, said they would prefer option B, which is again $1.9 billion over eight years. And 21% said they were not sure.”

In contrast, while SDOT’s poll found both options polled well above water with support, the margin of support on a hypothetical $1.2 billion poll was greater than the $1.7 billion option. However, the City’s pollster did not offer a $1.9 billion option and choose to split the sample rather than simply ask voters directly if added investments would increase the propensity to support the levy.

NPI’s poll suggests that when presented with two levy options, Seattle voters prefer the bigger one, as advocates — including The Urbanist and many of the poll sponsors — have been pushing them to do. [Note: The Urbanist’s advocacy staff and volunteers participate in coalitions independently of our editorial team.]

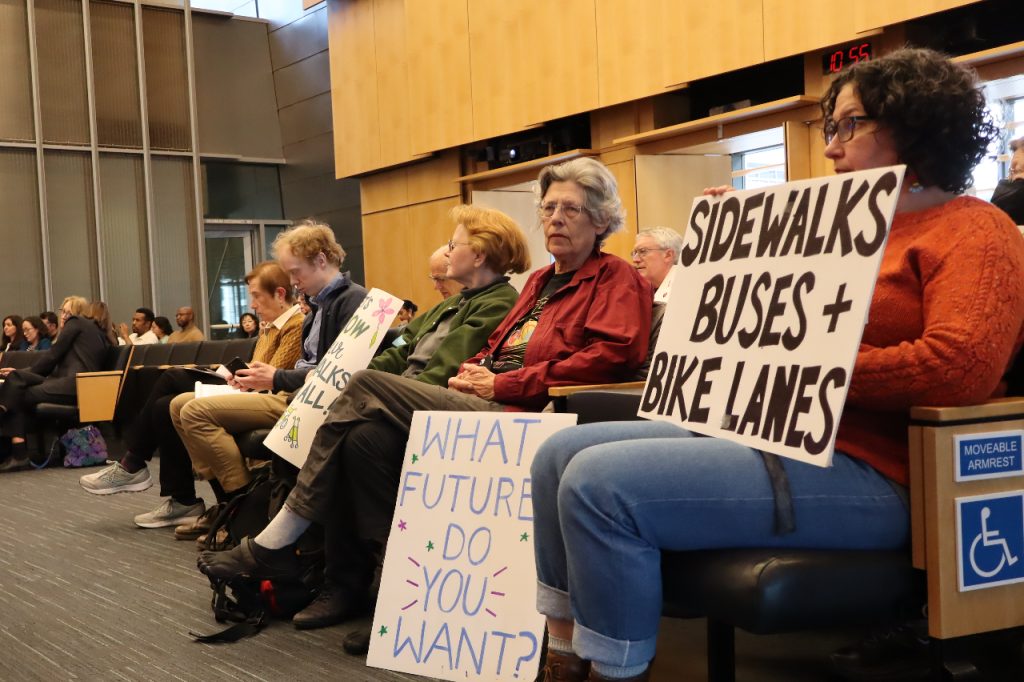

Advocates stress transforming streets for safety

Katie Wilson, general secretary of the Transit Riders Union, spoke at City Hall to urge city council to up the investments in transit. She cited surveys showing the lack of speed and reliability is hindering transit use and jeopardizing the City’s climate goals, which call a mode shift away from driving and toward greener alternatives.

“We are thrilled to see the strong support for public transit investments in this poll. We know that improving our public transit system, making sure that we have fast, affordable, and reliable public transit is one of the best ways to get people to switch from driving, which is absolutely necessary if Seattle is going to reach its mode shift goals by 2030. So we hope that the city council will take the results of this poll to heart and step up public transit investments in this body.”

Clara Cantor, community organizer with Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, urged the council to do the same with sidewalks and safe streets upgrades.

“We are excited to hear that Seattle voters are fully supportive of a significantly larger levy, specifically one that invests above and beyond what the mayor’s proposed in sidewalks and in safe streets, and that they’re willing to pay for that,” Cantor said. “Seattle voters really value a transportation system that keeps everyone safe that balances sustainability and equity and really get us to a future that we can move around our city freely.”

Cecilia Black, an organizer with the Disability Mobility Initiative at Disability Rights Washington, said the lack of sidewalks was a huge issue denying mobility to the disabled community. For wheelchair users like herself, streets without sidewalks become impassable.

“Over 60% of our streets are not accessible because either broken or missing sidewalks,” Black said. “And the city council has said they want a once in a generation investment in sidewalks. So this is an opportunity to do that. And like Andrew said, if they leave money on the table, that is not following through on a once in a lifetime investment in sidewalks.”

Another project that found strong support was pedestrianizing Pike Place, with a question worded as “Limit automobile traffic in Pike Place Market to open up more space for vendors, seating, art, or music while still allowing for business loading and unloading.” The poll found 65% of respondents said they’d be more likely to vote for a levy that included that project versus just 12% who opposed the project and said it decreased their support.

The popularity of Pike Place pedestrianization may be news to D7 Councilmember Bob Kettle, who initially proposed to completely jettison that idea from the next levy, but later softened and instead proposed a full Seattle Process with a wide range of stakeholders before pledging changes to Pike Place in the near future.

Council’s initial reaction

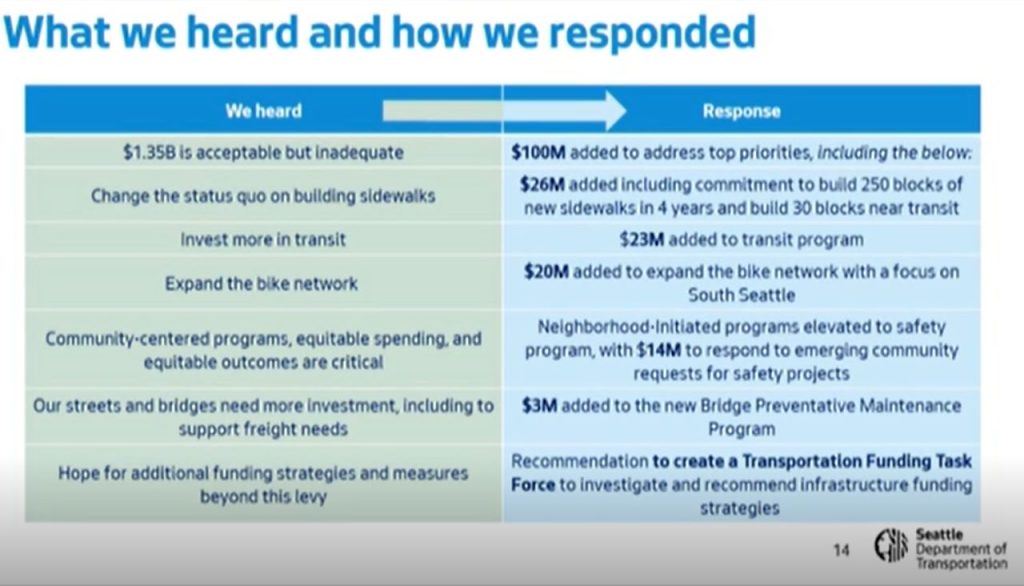

Following the press conference, the Seattle City Council’s Select Committee on 2024 Transportation Levy received their first presentation on Mayor Harrell’s proposal. In the questions and discussion they generated afterward, signals were mixed as to whether councilmembers were ready to up the ante on levy size, with members not really pressing on the issue.

SDOT’s presentation largely focused on how the existing eight-year $1.45 billion proposal is adequate and meeting the challenge. SDOT Director Greg Spotts said co-creating smaller, granular projects with community members was his preference over focusing on broader corridor-wide approaches and large projects.

While several councilmembers stressed the need to improve safety and prevent fatal crashes, bridge maintenance and replacement also was a clear priority, particularly for Kettle and transportation chair Rob Saka. Saka and Kettle stressed the importance of the Magnolia Bridge, which serves a well-to-do enclave of about 20,000 residents on the Magnolia Peninsula, along with two other bridges to the north that also span the BNSF’s Balmer Railyard. Under the levy, the Magnolia Bridge would see some upkeep, but it would not fund a pricey full replacement, which could cost the better part of a billion dollars.

CM Bob Kettle is touting the improvement made under the current levy, citing 2nd Ave's bike lanes and bringing up the death of Sher Kung.

— Ryan Packer (@typewriteralley) May 7, 2024

"If we have what we have today, in August of 2014, I don't think she'd be killed."

Kung's death was a big impetus behind those lanes.

Saka and Kettle also shared their regrets and condolences over the death of Sher Kung, a prominent lawyer who was killed biking on Second Avenue in 2014. Kung’s death galvanized support to finish the protected bike lane on Second Avenue, which the Seattle Times had criticized before and after as too costly. Since the protected bike lanes went in, nobody has been killed in Second Avenue crashes, but similar treatments have been slow to expand to other streets, especially in South Seattle, but have arrived eventually in several other corridors in center city and North Seattle — albeit with some corners cut.

Especially where safety facilities are lacking and speeding remains rampant — places like SoDo, Southeast Seattle, and Aurora Avenue and Lake City Way in North Seattle — traffic deaths and serious injuries have stubbornly persisted. Advocates have specifically called out these corridors and hotspots for investments and redesigns. In 2015, Seattle adopted a “Vision Zero” goal to end traffic deaths and serious injuries by the year 2030. In November, Seattle Greenways placed nearly 230 markers around the city to honor the people who died in collisions since 2015, a grim reminder that Seattle it not on pace to meet its Vision Zero goal and the toll is high.

Will Seattle City Council act proactively to prevent other people from meeting the same tragic fate as Sher Kung? It’s too early to tell. The question of whether Seattle will increase the levy package beyond its current $1.45 billion scope remains an open one.

Council’s committee on the levy now has official public hearings and deliberations scheduled for 4:30pm on May 21 and June 4, as they try and meet their deadline of approving final levy ordinance by early July, sending it to voters in November.

Ryan Packer contributed greatly to this reporting.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.