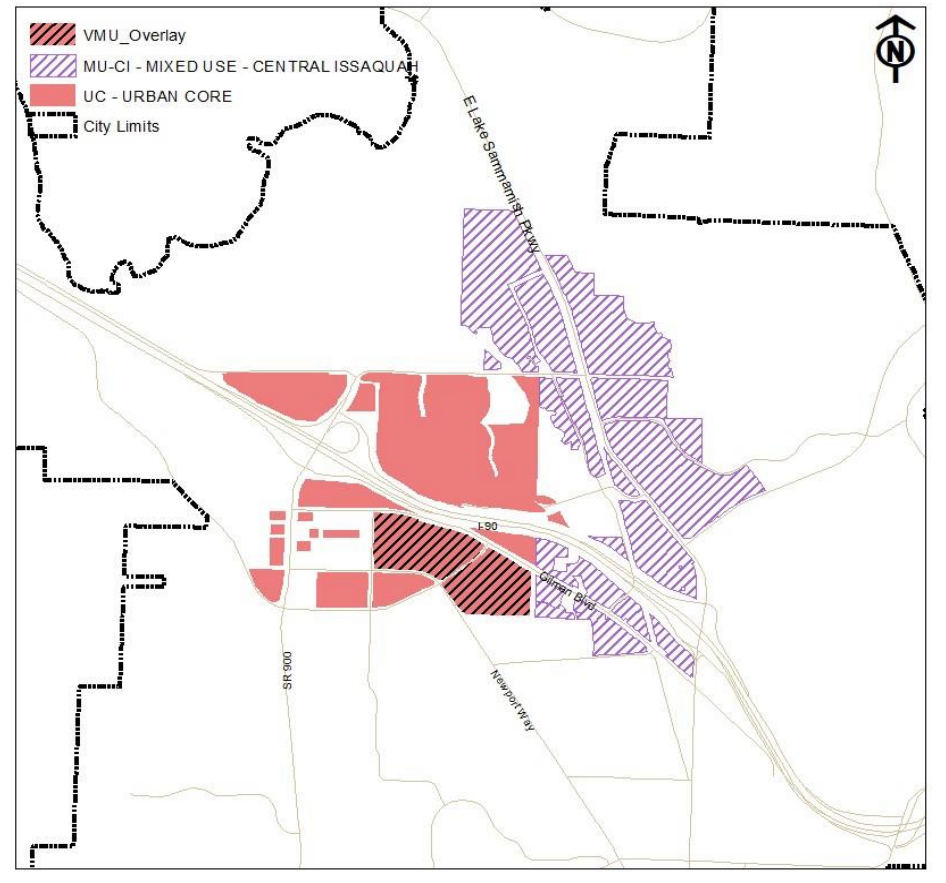

The Issaquah City Council this week voted to approve a tax exemption intended to spur the construction of denser mixed-use housing in its transit-rich central city, where the city’s planned light rail station is set to open sometime in the 2040s. The Central Issaquah Pioneer Program, as its name implies, is intended to get the ball rolling on multifamily housing in the areas around Gilman Village and across I-90 around East Lake Sammamish Parkway and the East Lake Sammamish Trail.

The 5-to-2 vote, with Councilmembers Chris Reh and Tola Marts opposed, reflects two competing visions for the suburban city, and discussions ahead of the vote focused on whether Issaquah should be lowering barriers to housing new residents or whether it should continue to avoid offering the types of incentives that other regional cities have long been offering to spur growth. Last fall, The Urbanist covered comments Marts made as the Pioneer program was moving forward, in which he asserted that Issaquah was “choking” on the amount of development that had occurred in the city.

However, five councilmembers — Council President Lindsey Walsh, Victoria Hunt, Barbara de Michele, Zach Hall, and Russell Joe — held firm Monday night. This majority presented a vision for Issaquah as a city that continues to make way for new residents while using the policy tools available to add new affordable housing. The proposal, which lowers the existing affordability mandates that come with new apartment construction in Issaquah, is set to serve as a pilot for housing incentive programs more broadly. Housing production in Issaquah has been fairly anemic, with no permits issued for any new apartment buildings in the city for all of last year and a sharp decline in overall building permits since the city instituted steep affordability requirements.

The Central Issaquah Plan, intended to lead to a more dense urban core where existing land uses are mostly big box retail and strip malls, actually dates to 2012 but clearly hasn’t had the desired result to date. The incentives approved Monday would apply to a maximum of two developments, but those projects could bring as many as 400 units each, and act as a catalyst for future development in the area.

Councilmember Lindsay Walsh shared takeaways she gleaned from attending the recent grand opening for Sound Transit’s 2 Line, between Redmond and Bellevue, where both cities have been planning for increased density around their planned stations for years.

“It was really amazing to be in communities that have really created transit-oriented development, with affordable housing and things like that that bring a community together,” Walsh said, noting that adding new residents closer to transit will reduce the amount of traffic impacts that come from population growth.

“The current residents of this city are not the only stakeholders in this situation,” Walsh said. “We do not have the ability to gatekeep our community to additional development.”

Councilmember Russell Joe also brought up the need to bring future residents of Issaquah into the conversation. “The difficulty that we sometimes have is that we’re planning for a future, and a future of people who don’t live in our community yet, but would like to live in our community. How do we provide the housing stock and the supply for them to move to our community?” he asked his colleagues ahead of voting yes.

But that pro-growth vision wasn’t able to win over the two councilmembers in the minority on Monday’s vote, with both Marts and Reh adamant that Issaquah not provide what they both described as a giveaway to developers to get them to build housing in Issaquah.

“Issaquah’s a pretty darn desirable place to live, and to build, and to develop, and, quite honestly, I don’t see the need for making this kind of a subsidy to developers to get them to build in Issaquah. I don’t think it’s necessary, fundamentally,” Reh said. “I just can’t go back to the people I live next to and say ‘hey, we’re going to pay developers an extra $8 million dollars to develop in this community.'”

The “subsidy” that Reh references is actually foregone tax revenue for the eight-year lifespan of the multifamily tax exemption across all taxing districts that would receive funding; the actual expected cost in foregone city revenue is only projected to be around $84,000 per year.

“I think it’s a bad deal. I think we could have gotten a better deal,” Marts said. “If we say that transparency is important to us, the voters are telling us time and time and time again that traffic is hugely important and the large, looming cost of deferred infrastructure […] will only get worse with 800 more potential units in the city.”

Marts said he would like to see the city set its affordability mandates at closer to 20%, even as those policies have not led to the creation of significant amounts of affordable housing.

“I think our valley is worth more than this. I think we’re selling it cheaply,” he said, citing Monday’s vote as the hardest vote he’s ever taken in 15 years. In 2012, Marts was on the council when the city adopted the Central Issaquah plan, along with now State Senator and gubernatorial candidate Mark Mullet.

In her comments before the vote, Councilmember Walsh indirectly responded to calls for the affordability mandates to be set higher. “It’s important to recognize that this additional development on the valley floor was always allowed,” she said. “Yes, we were looking to get a 5-to-1 ratio [of affordable units], but nobody built that. You know where they built? They built in Bellevue, and Redmond, and Kirkland.”

Deputy Council President Barbara de Michele said Monday’s vote reaffirms the Issaquah council’s commitment to bringing light rail to Issaquah. Currently, Sound Transit is working to fill a $90 million budget gap in its financial plan for the planned South Kirkland-Issaquah Link line, originally set to open in 2041. If that gap can’t be filled, the timeline for opening would be pushed to 2044.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.