From e-bike rebates to congestion pricing, policy should incentivize healthy, eco-friendly choices.

This week, the Seattle City Council begins debating the mayor’s proposed transportation levy. Advocates fear the package may fail to invest adequately in transit, bike, and pedestrian improvements, raising questions as to how serious the City is about achieving its own 2030 mode-shift goals, which seek to decrease reliance on cars, as reiterated in last year’s Climate Change Response Framework. Add to that a lackluster Comprehensive Plan proposal that will leave people struggling to find housing they can afford near their jobs and destinations, and we seem headed toward another decade of car-choked streets.

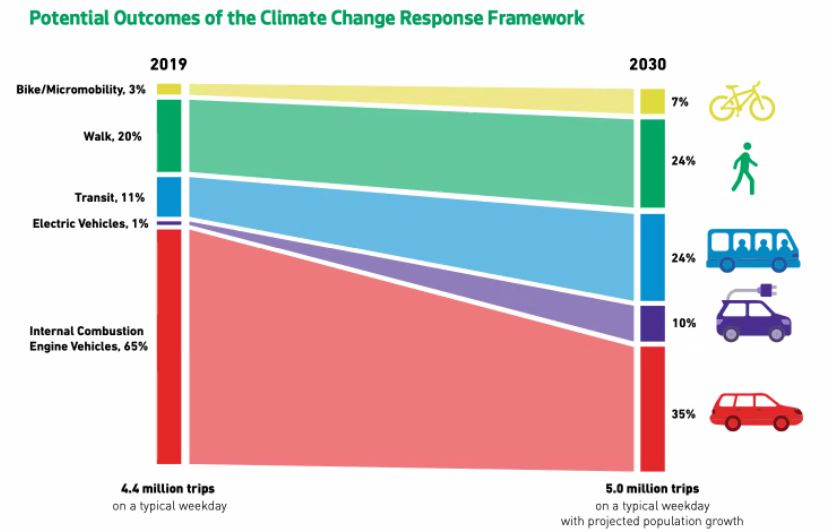

Imagine it’s November 2027 and a progressive slate of district council members just swept the election, joining the progressive mayor and citywide members elected in 2025. (Stay with me! It could happen!) They have only three years left to shrink the portion of weekday trips made by internal combustion engine vehicle to 35%, and there hasn’t been a lot of progress since 2019 when these stood at 65%. What can they do?

Beyond trying to make up for lost time on multimodal infrastructure, right-of-way allocation, and zoning, there’s a whole suite of policies the City could implement to achieve a dramatic mode shift in short order — ones that some cities around the country are busily putting into practice. I’m talking about creating incentives that make it more expensive to drive and less expensive to ride transit, bike, walk, and roll: shifting transportation habits with cold, hard cash. Let’s take a look.

1. Electric bike subsidies

Whenever I converse about e-bikes with someone who owns one, they tell me it totally changed their travel habits. They ride it to work because they don’t arrive sweaty. They haul groceries and pick up their kids. They leave the car at home, or even sell it. I’m almost afraid to try one out myself, for fear of abandoning my well-loved Raleigh. What if I’m born again as an e-biker?

You don’t have to believe my anecdotal evidence. Recent research shows that e-bikes really do reduce car trips and car ownership. But there’s one big barrier, beyond needing safe and connected bike infrastructure that can accommodate e-bikers at scale: they’re expensive. An entry-level model will run you about a grand, but you can easily drop a few thousand dollars or more, especially for cargo and kid-hauling models. And let’s face it, to ditch the car, you need to be able to carry stuff.

Washington state’s new e-bike rebate program, anticipated to start later this year, will subsidize the purchase of some 8,500 e-bikes statewide — a fraction of total demand, so it’s likely to go fast. The rebate will cover $300 at the point of sale, or $1,200 for low-income purchasers. The Legislature approved an additional $2 million for e-bike lending programs.

This is a good start, but there’s no reason Seattle can’t go further. California also has a state e-bike incentive program launching this year for households up to 300% of the federal poverty level, but a number of California cities and counties also offer their own substantial rebates. In Redding, to pick just one example, income-qualified residents who participate in the city’s utility discount program are eligible for $1,150 off an e-bike purchase.

Some of the local California programs appear to have run through their available funds. Instead of allocating a set amount for a pilot or a one-time blitz, Seattle could create an ongoing funding stream for e-bike subsidies. And why not raise this revenue in a way that accomplishes another mode-shift goal? Here’s one idea:

2. Weight-based vehicle taxes and fines

US cars have been getting heavier for decades. Heavier vehicles cause more wear-and-tear on the roads, and they’re more deadly. While changing the design of our streets is the best way to prevent drivers from killing people, reducing the use of SUVs and other large personal vehicles would help, too. One way to do that is to make driving those vehicles more expensive.

Last year, Washington, D.C. approved a steeply graduated vehicle registration fee based on weight. Passenger vehicles weighing less than 3,500 pounds pay $72, while those weighing 6,000 pounds or more pay $500. (Some jurisdictions in other countries have gone much further, but I’m trying to stick to US examples.)

Unlike D.C., which has the powers of both a city and a state, Seattle cannot set its own vehicle registration fees without authority from the Legislature. However, there are other ways the City can raise revenue while disincentivizing the use of heavy cars and trucks.

Seattle could consider scaling parking permits and meter rates to vehicle weight. Currently, restricted parking zone (RPZ) permits top out at a measly $95 for a two-year period. For comparison, a spot at my apartment building on Capitol Hill now costs $160 a month — in a secure garage, but still! Parking meter rates are low, too. The average on-street parking rate is about $2.70 per hour, while private off-street lots average about $5 per hour. In other words, the City has a lot of room to increase parking revenue by charging the drivers of large and heavy vehicles closer to market rates.

The City could also consider weight-scaled fines for various traffic violations: parking infractions, block-the-box, red light and school zone camera tickets, and so on. After all, when the drivers of SUVs and other large and heavy vehicles break the law, they’re more likely to cause death and destruction. The state sets a maximum $250 fine for most traffic infractions, but there’s nothing stopping the City from establishing graduated rates below that ceiling.

How much revenue could be generated in this way? Last year, City staff estimated that an across-the-board parking meter rate increase of 50% would raise $10 to $13 million annually. I’d bet a weight-based approach to parking permits, meter rates, and traffic fines could generate at least that much, maybe more. That could fund one hell of an e-bike rebate program.

3. Mandatory employer transit subsidies

What about incentivizing public transit? Thanks to an ordinance passed back in 2018, Seattle employers with 20 or more employees must allow their employees to make a monthly pre-tax payroll deduction for transit expenses. But the City could go further and actually require employers to subsidize transit passes for their workers.

I’m kind of breaking my own rule here, since I’m not aware of any US city — or any city, for that matter — that straightforwardly mandates employer transit subsidies. But I like to think that Seattle already has a law like this in place in some not-too-distant parallel universe, since this was the campaign I was working on with the Transit Riders Union back in 2020 when COVID-19 shut down business as usual.

Of course, many large employers already fully subsidize employee transit passes. But not all do, and the workers getting short shrift tend to be the lowest paid — and their jobs can’t be done remotely. Think grocery workers, hotel workers, retail workers in the downtown core. If you’re a tech worker at Amazon or Starbucks HQ, you get an unlimited ORCA pass; if you’re a cashier at Amazon-owned Whole Foods or a barista at a Starbucks coffee shop, you’re out of luck. A well-designed mandatory employer transit subsidy could right this inequity while also increasing transit ridership and reducing drive-alone commuting.

4. Mandatory parking cash-out

The City could also act to ensure that employers aren’t creating incentives for their employees to drive to work. In 2020, Washington, D.C. passed a Transportation Benefits Equity Act that went into effect early last year. It’s essentially a parking cash-out law, a concept developed by urban planning guru Donald Shoup. Employers with 20 or more employees that offer free or subsidized parking are required to pay the market value cash equivalent of this benefit to employees who don’t use it.

There are some tricky challenges to designing an effective policy along these lines, and while it’s too early to assess how the D.C. law is working in practice, it seems to get a lot right. For example, unlike California’s long-standing and largely unenforced parking cash-out law, it defines a procedure for determining market value, so it’s clear what employers must pay. (A bill passed in 2022 may improve California’s law, which so far has only been consistently enforced in Santa Monica.)

Parking cash-out is tied to larger questions about how cities govern the development and leasing of commercial real estate. As long as there are parking minimums requiring developers to build garages and as long as extended business leases include vast seas of parking spots, it’s a little perverse to tell employers they have to pay their employees not to use an amenity they’re locked into paying for themselves. A parking cash-out law would probably have to wait, as the D.C. law does, to kick in when an employer’s lease expires or is up for renewal, giving them a chance to renegotiate terms. Ideally it would be coupled with axing parking minimums and unbundling parking from commercial leases altogether.

Mandatory parking cash-out laws have a lot of potential to reduce car commuting, as a recent study for the Federal Highway Administration shows. The most dramatically effective scenario this study analyzed went even further, prohibiting employers from subsidizing parking and mandating a $5 daily bonus for each day an employee doesn’t drive a single-occupancy vehicle to work — inspired, probably, by Seattle Children’s Hospital’s notable transportation program.

5. Congestion Pricing

An article on transportation incentives wouldn’t be complete without at least a mention of two more big policies that, while politically and logistically challenging, could be great if done well. The first is congestion pricing (or decongestion pricing for those who prefer a positive framing), which Seattle studied pricing in a preliminary way in 2019, and which is about to go into effect in New York City (or, more precisely, south Manhattan) this summer.

The new decongestion tolls — generally $15 for cars and more for commercial vehicles — promise to reduce vehicle traffic and raise a pile of badly-needed cash for MTA public transit capital improvements. Notably, there are some discounts and exemptions for low-income drivers and people with disabilities. New York will be the first US city to implement congestion pricing, and it’s been a long and rocky political road to get there, so it will be fascinating to see how it plays out.

6. Free transit

Finally, what better way to incentivize public transit use than to make it free? I wrote about the promise and pitfalls of free transit a few years ago over at Publicola. Since then, Boston and New York City have both piloted fare-free transit on a few specific bus routes.

Most of the US transit agencies that have gone entirely fare-free are much smaller and less reliant on fare revenue than King County Metro and Sound Transit. Our multiple transit systems, operated by different agencies and serving different geographies, pose logistical challenges to any fare-free scheme. But with a robust enough revenue source — like an employer tax to replace the transit benefits that employers would no longer have to supply — it’s well worth exploring how going fare-free in Seattle could work.

Any of these six policies, done well, would accelerate mode-shift in our city. Together they’d be powerful indeed. Of course, these incentives can only work as well as our transportation system. We must also resolutely refashion our public right-of-way to prioritize the zero-emission modes people need to use if we’re going to meet our climate targets, and rezone Seattle’s neighborhoods so that people can get where they need to go using those modes. We may have to wait for new city leadership to pursue forward-looking transportation incentives, but now’s the time to make the Seattle Transportation Levy and Comprehensive Plan as good as we possibly can.

Katie Wilson is General Secretary of the Transit Riders Union, a Seattle-based organization advocating for improving transit quality and making access more equitable.