Seattle Times columnist Danny Westneat has put himself on the case of fixing Downtown Seattle’s Third Avenue bus mall. There’s just one problem: he has absolutely no idea what he is talking about.

In his May 4th column, Westneat argued shunting bus traffic off Third Avenue and letting cars back on would somehow revitalize the street, and inject foot traffic into businesses along it. If the immediate presence of cars was the elixir of urban vitality, then the most vibrant and successful parts of cities would abut freeways and highways, but everyone knows that’s not the case. Those areas are dead zones.

Third Avenue does have issues with retail vacancies, drugs, and crime, but are buses to blame? That’s quite the leap. But Danny went there. In fact, he posited cars are the key ingredient in “complete streets” and buses the sour note, which is surely news to actual professionals in the field of urban design and planning.

“Third Avenue though is the opposite of a ‘complete street.‘ It’s a monoculture — it’s got buses and that’s it,” Westneat wrote. “There are generally few pedestrians, except in the area of The Blade. And there the crowds are often engaged in more of an underground economy.”

Get cars back in the mix and the business will roar back and the criminals and junkies will shrink in fear, goes Westneat’s theory apparently. Unfortunately, Westneat is in tinfoil hat territory as far as what actually promotes high-quality urban commercial streets, and co-opting an urbanist term to push his case is a slippery move. In contrast, The Urbanist editorial board wrote in 2022 that transit was a key part of Third Avenue’s success and efforts to remove bus lanes were misguided:

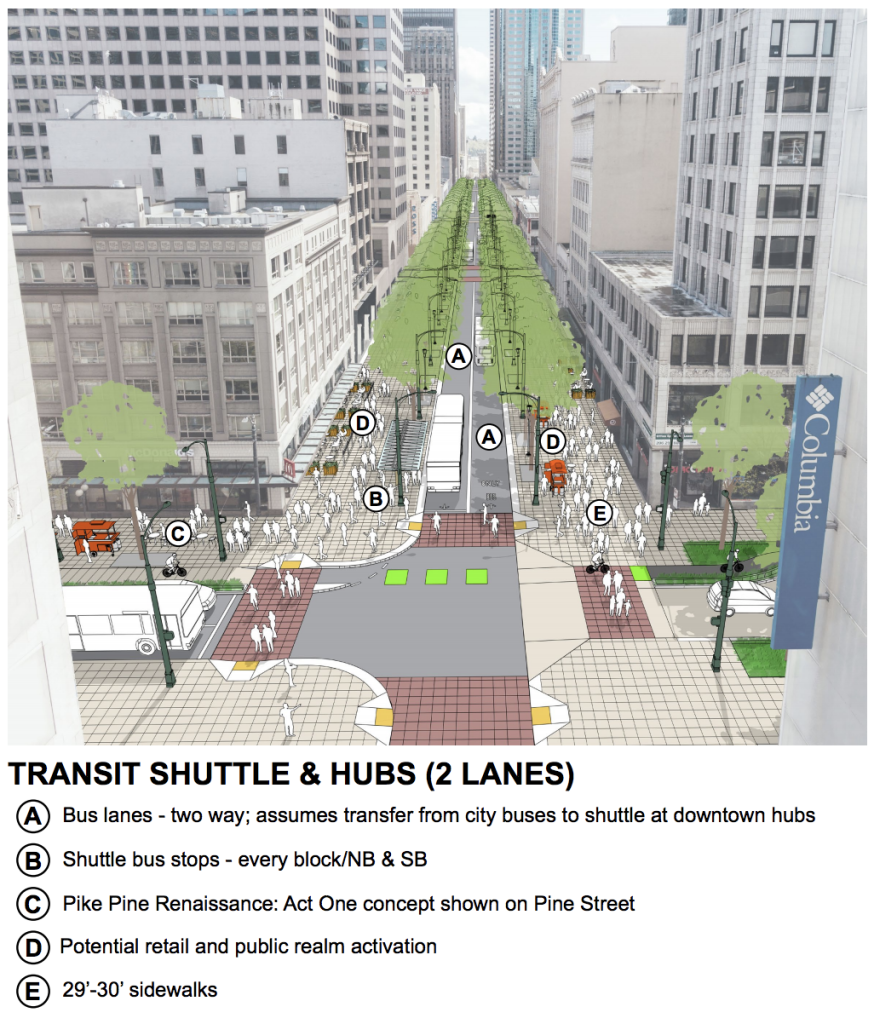

“At The Urbanist, we believe the Third Avenue plan must focus on improving transit service and pedestrian safety. Some sections have great opportunities for street art, pocket parks, and sidewalk cafes. If we make the street more walkable and the bus stops pleasant, safe, and busy, then street life will follow.”

But it’s been like yelling into the void as columnists like Westneat and leading business gurus (and the powerful Downtown Seattle Association, or DSA) lobby for the idea of diluting transit on Third, presenting it as a panacea for everything from attracting high-end retail to curbing crime and disorder.

Never mind that Mayor Bruce Harrell and Seattle’s new crop of city councilmembers were elected promising that they had the solution to crime, homeless encampments, and economic recovery. Campaign pledges to push encampments out of Downtown and tackle crime by fully funding and supporting the Seattle Police Department have not borne fruit. And of course Seattle Times columnists will cover for them. Hence we’re sitting here talking about if buses cause crime rather than a lack of progress on homelessness and crime and poverty downtown.

Westneat notes the latest iteration of this brilliant kill-the-bus-mall idea came from a former Microsoft executive named Steve Sinofsky who lives downtown and obviously knows best since he took to Twitter to bravely broadcast his ideas. “Bus stops killed that area,” Sinofsky claimed. Sinofsky ran Microsoft’s Windows division for three years so surely he’s an expert, right? Little known fact: top software whizes are also great at open-heart surgery, rocket science, and Freudian psychoanalysis. Let’s just let them run the world and not ask too many questions!

Unfortunately, writing for The Urbanist for a decade has left me with a compulsion to ask questions, so I cannot help myself.

Unlike Sinofsky, Westneat sort of admits the relationship between buses and crime is not causally linked — one can imagine he did several minutes of Googling just in case there was a study out there… But even admitting the lack of casual relationship, Westneat said there’s “synergy” between buses and crime and therefore proceeded to spend the rest of the piece riffing on their linkage and pretending the City can control crime by reducing transit access.

“I doubt there’s much causal relationship between a bus-only corridor and drug markets. But there is some synergy,” Westneat wrote. “The police say drug markets can and do piggyback on the shifting crowds at bus stops, even as it obviously isn’t the case that bus stops prompt urban disorder all on their own.”

Sinofsky actually made exactly that claim: “Every single day for a decade I watched the busstops grow and grow until McDonalds closed the dining room. Until the food court next door closed. Until the convenience store turned into a head shop. Please tell me how loitering and open air drug use at the sheltered bus stop is not causal to all those?”

One of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s first moves upon taking office was to close one of Third Avenue’s most heavily used bus stops as a way to deter crime, a move that clearly hasn’t led to those stops becoming less problematic.

Westneat seems to talk himself into a full circle as he declares buses and crime Third Avenue’s brand and that one of those two things has to go to save the street.

“It would surely be nicer to stroll along the avenue, though, or to run a business there, if it were more of a complete street,” Westneat concluded. “Some city boosters have also branded Third Avenue as ‘Seattle’s front door.’ So think of it this way: If we were starting from scratch, would anybody ever agree that our city’s front door ought to be a giant bus mall?”

Yes they would! It’s bizarre to argue bus malls don’t belong or make a great front door for a city, and it’s a car-brain take to argue otherwise. If downtowns want to be well-connected to the rest of the region, they should want bus malls. But the Third Avenue bus mall can certainly use improvements.

Westneat’s piece acknowledged another planning effort underway: “This past week, the Urban Land Institute released a report with ideas on how to fix Third Avenue. It scarcely mentions buses. The group was chaired by attorney John Hempelmann, who lives downtown,” Westneat wrote. “Hempelmann said planners worry the adjacent avenues might not be able to handle many of Third Avenue’s buses.” This builds on numerous pushes from the DSA to redesign the street, the most recent in 2022 and 2019.

“Hempelmann’s group instead recommended a series of immediate cosmetic fixes to Third Avenue. Such as: daily cleaning of streets and curbs, brighter lighting, new bus shelters, more street events and a formal city program to appoint block watch captains,” Westneat wrote. “The report suggests the city ‘invite joy through banners, art, and branding,’ intended to spread the avenue’s ‘unique identity.’

The DSA and Urban Land Institute Third Avenue upgrade plan looks like it may secure some funding through $15 million earmarked in Mayor Harrell’s transportation levy package, set to go to voters in November. It’s enough for some nicer lighting and bus shelters, but it will not move mountains.

Some of the obstacles to a vibrant Third Avenue relate to growing pains and stalled construction projects on the corridor. The Civic Square block has been a vacant pit for more than a decade due to a series of blunders and missteps between City Hall and a carousel of developers trying to realize a luxury residential skyscraper at the site. Work on a 36-story office tower to be called “The Net” at Third and Columbia Street has been abandoned in reaction to the precipitous drop in office demand during the pandemic and the work-from-home trend that ensued.

Elsewhere, construction soldiers along, such as the 47-story apartment tower at Third and Virginia, but until projects are complete, they will break up the streetscape rather than enhance it. But, once done, projects like this one should bring welcome improvements, with street-level retail and housing for new residents, filling out a street with too many parking garages and blank walls, rather than active uses and attractions.

Many of Third Avenue’s ills are symptoms of larger problems. We need to get people living in encampments the care they need, including permanent supportive housing. If we want theft to decrease and black markets to disappear, we need to provide real economic opportunity for the poverty-stricken. If we do not want to be around people having mental health episodes, we need to rebuild our social safety net and repair our ailing mental healthcare system.

Most of these problems do not have quick fixes. And simply shunting buses away shouldn’t even be on the radar as a serious quick fix.

As silly as these ideas are, we shouldn’t be surprised. It’s been a long tradition among Seattle pundits and bigshots to look at transit as a nuisance easily jettisoned rather than a key ingredient in the city’s economic success and achieving long-term goals for livability and sustainability. But eventually bad ideas have to be put to bed and we have to embrace transit — not just shiny trains but also unsexy workhorse buses — as an integral part of the identity of this city.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.