The $1.35 billion, eight-year transportation levy proposal unveiled by Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell early this month has drawn broad criticism from transportation advocates who note the plan’s lack of concrete goals and targets and a significant tilt of proposed spending toward road and bridge maintenance projects. So far The Urbanist has taken a deeper dive into the details in the proposal, including the citywide repaving projects, bike investments, and promises to expand the sidewalk network that could be advanced with funding from the new levy.

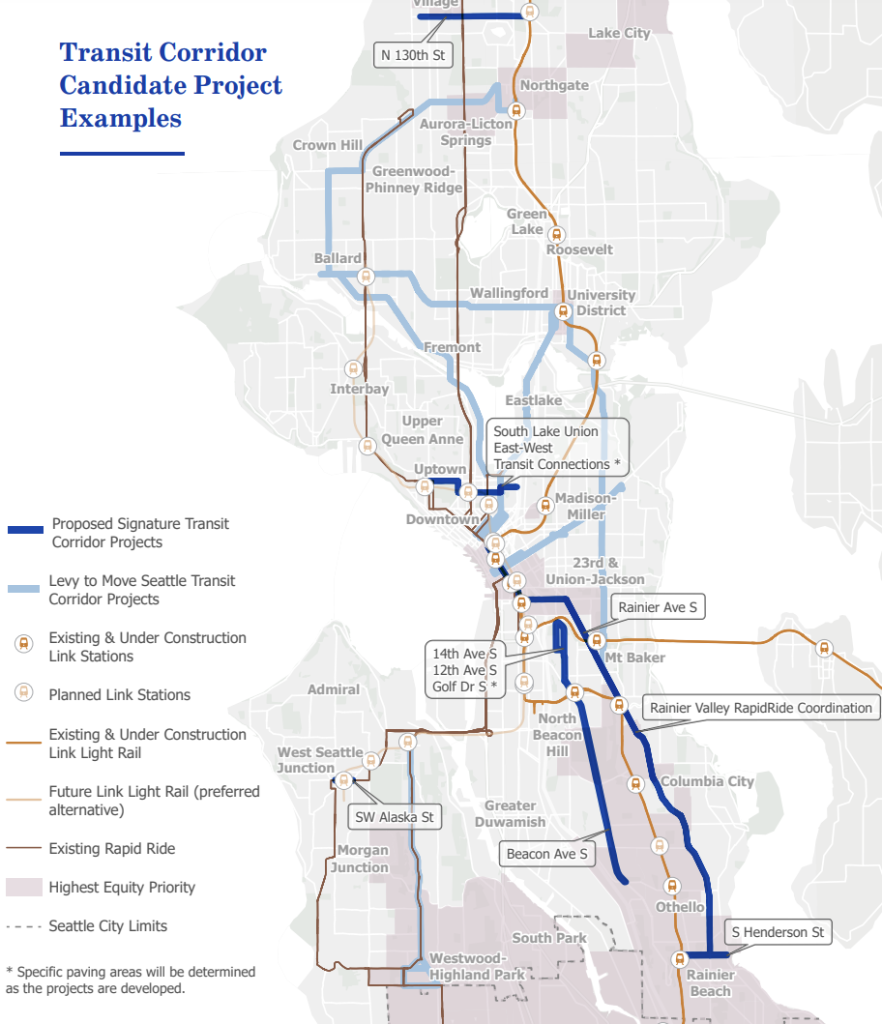

But the proposal’s biggest step back compared to the 2015 Move Seattle Levy is in the area of public transit investments. The proposed $121 million in transit spending represents a direct reduction in total dollars from current spending. Move Seattle allocated around $150 million for transit projects — and earned considerable federal matching funds on top of that. With inflation factored in, the total spending on transit projects would be set to decrease by around 30%. This proposal also represents a back scaling-back of what the city promises to deliver. Where Move Seattle committed to major transit upgrades on seven individual corridors around the city, this proposal includes just two, with partial upgrades on another three stretches of roadway used by frequent buses.

Only one full upgrade to RapidRide, King County Metro’s highest level of transit service, is proposed, for the Route 7 between downtown and Rainier Beach, a corridor promised to voters in Move Seattle but scaled back in response to budget pressures in 2020. Despite the fact that Metro is currently analyzing other routes in the city for RapidRide upgrades, including the 36, 49, and 40, the draft includes no specific commitments beyond making additional improvements to the 36 corridor, a project that Metro has already started work on.

The lion’s share of transit funding appears set to be spent on a commitment to 160 “spot improvements” that can range from an improved bus stop, an upgrade to a signal to provide transit priority, or a stretch of transit lane. Currently, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) funds spot improvements from the city’s other dedicated source of transit funding, the Seattle Transit Measure, which voters approved in 2020. They can have an incredible value on a per-project basis, but a switch to primarily implementing spot improvements means less accountability for what projects actually get accomplished during the levy’s lifespan — and whether they actually add up to significantly better service for riders.

“This proposal’s lack of specificity for transit, mak[es] it appear as if it could be a slush fund for car-oriented projects,” Ben Broesamle, treasurer and operations director for Seattle Subway, told The Urbanist. “And that’s entirely unacceptable to us, as transit advocates who lived through the Move Seattle Levy and were promised a lot of great things for transit and didn’t receive them.”

The Move Seattle Levy is set to deliver three RapidRide lines, including the H Line along Delridge Way SW into Burien, which opened last year, the G Line along Madison Street, set to open late this summer, and the J Line through Eastlake to the University District, starting construction this year and opening for service in 2027.

But four other routes only received spot upgrades that ranged in their ambition: upgrades to the Route 40 getting underway later this year include transit-only lanes along Westlake Avenue and through the heart of Fremont and Ballard at some of the most problematic spots along that route. On the other end of the spectrum, upgrades to the Route 48 between the University District and Mount Baker only include a short stretch of transit lanes, with signal priority the only corridor-wide improvement.

Upgrades to the Route 7 included sidewalk repair, some small safety upgrades, and a small southbound stretch of bus lane. Confusingly, a larger stretch of northbound bus lane was advanced separately from the corridor upgrade project, illustrating the chaotic, piecemeal nature of the city’s current transit improvement plans. Key bus lane segments identified by Metro were left out of either upgrade.

Without the more ambitious goals of Move Seattle, it’s unclear if City leaders would have persevered through three years of sustained pushback on the idea of giving transit priority to the Route 40 if it hadn’t clearly been articulated to voters who approved the measure by a 17-point margin. And this levy proposal is also likely leaving federal dollars on the table for transit projects: large grant awards like the $64.2 million provided to RapidRide J and the $59.9 million for the RapidRide G wouldn’t have been available without a sizable local match set aside to move large capital projects forward. Seattle is already set to leave a significant amount of federal dollars on the table by not having any significant projects in the pipeline during the tenure of 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

This levy represents the biggest opportunity the Harrell Administration has had to present its vision around transportation, and that vision seems to be a restrained one that rhetorically emphasizes the importance of transit riders without putting forward a comprehensive plan for how the city can achieve its goals around increasing transit ridership, a move that the entire county’s climate goals are dependent on.

Ashwin Bhumbla, a member of Seattle’s transit advisory board and liaison to the official Move Seattle Levy oversight committee, told SDOT representatives early this month that the proposed transit investments were positive, but didn’t seem to match up with the scale of the proposed levy and its lifespan, which will extend until 2032, and the needs riders have identified.

“When we’re talking about mode shift, the two main things […] that make people ditch their cars and go into transit and create a safer and more climate resilient city, are the frequency and the reliability of the system,” Bhumbla said. “And so I think it’s great that you’re identifying two routes for that. But it’s concerning that this is our big push, the biggest transportation levy in Seattle history, and it’s like, really those two large projects that we can commit to over the next eight years.”

A coalition of transportation advocacy organizations and community groups, which includes Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, Puget Sound Sage, Seattle Subway, and The Urbanist, are pushing for an additional $52 million to be added to the levy to reverse cuts to overall funding for transit. The group is also pushing for the levy’s overall expenditures to be at least 50% focused on walking, biking, and transit investments, a move that would require a shift of at least $139 million. [Note: The Urbanist’s advocacy staff and volunteers participate in coalitions independently of our editorial team.]

Broesamle cited specific bus corridors that could utilize speed and reliability improvements that could be provided by that funding. “We need to work on more of our east-west bus routes that already exist, specifically routes 8 and 44, 45, 60, and 50, need help. Traveling east-west in the city, regardless of trying to go downtown, is really challenging.” He also cited a need to continue expanding the city’s trolleybus network, and to create a plan to connect Seattle’s two streetcar lines, two things that are completely missing from this draft proposal.

“We still demand action for real transit improvements, and time savings for transit riders in this city. If they are serious about equity, they will get serious about those riding public transit,” Broesamle said. “It’s really frustrating to be a transit advocate in this city. We are clearly setting ourselves up to repeat the mistakes of Move Seattle.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.