The draft $1.35 billion transportation levy proposal put forward early this month by Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell includes a broad array of goals for the city’s transportation system over the next eight years: repair 20% of the “major truck streets,” fix 34,000 segments of broken sidewalks, and implement safety projects on at least 12 corridors. But one high-profile target is completely missing from the draft: by how much will the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) expand the city’s network of protected bike lanes?

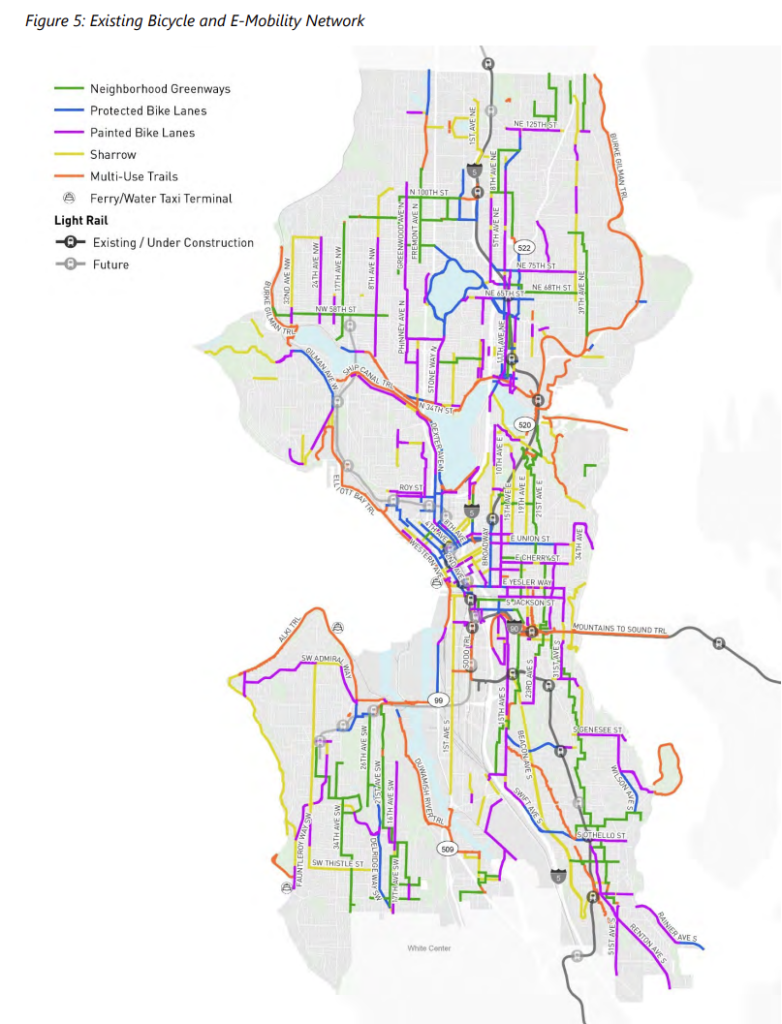

The expiring Move Seattle Levy committed to a bold target representing a dramatic expansion of the city’s bike network, with voters signing up to add 50 miles of protected bike lanes and 60 miles of neighborhood greenways across the city by this year. That target ended up being one of just three programs across 27 that the city isn’t on track to fully deliver by the end of this year, with the final tally likely somewhere between 90 and 107 miles. Getting to that final number required a considerable amount of heavy political lifting, and funding from multiple sources that were not the property tax levy itself.

This new “transportation levy proposal” — which is open for public feedback until April 26 — would allocate $94 million over eight years for upgraded bike facilities, an increase over Move Seattle even after accounting for inflation of around $10 million dollars. But it doesn’t set a baseline expectation for how much the network will grow.

“We don’t have a rough number,” Meghan Shepard, a deputy director with SDOT overseeing the development of the levy, said at a briefing on the proposal early this month.”We’re proposing to spend this month in broader community conversation. The [Seattle Transportation Plan] does lay the foundation for where expansions would occur, and we’ve already been hearing a lot from people who are excited about the bike network that we filled during the Move Seattle Levy and they see other places in the city, particularly in the south parts of the city, where we have the opportunity and they’d like to see additional investment.”

The draft levy does include some concrete targets — literally. One pledge is to upgrade 30% of the city’s existing bike lane network with more substantive barriers. This is the type of change that is being vividly illustrated downtown, on Fourth Avenue, as SDOT is in the middle of replacing the pant-and-post bike lane installed in 2021 with a concrete barrier. Upgrading existing bike lanes is popular with people who bike, and it also doesn’t require a conversation about reallocating any street space. While the previous levy was focused on mileage, this draft promises that all new facilities will come with concrete protection from day one, a promise that will likely increase average project costs.

Via its Complete Streets ordinance, the City has also set the expectation that a number of the planned major repaving projects, of which SDOT is pledging 15 using a record $423 million in street maintenance dollars, will include bike facilities. But in rolling out the draft levy without specific targets like number of miles of bike lanes, city officials argued that events like the emergency closure of the West Seattle Bridge and the Covid-19 pandemic pointed to a need to allow flexibility in spending.

“I think we do want to have more flexibility to make these investments in the places that are most needed as the city grows,” SDOT Director Greg Spotts said at the time the draft was announced. “If you wire them all in right now, then you may not be poised to adapt to places that become more dense and have more multifamily housing there.”

“Flexibility is important, but accountability is important, too,” Vicky Clarke, policy director of Cascade Bicycle Club told The Urbanist. “I’ve heard SDOT folks say that because there was those deliverables lined out, the Move Seattle Levy pushed the department to deliver. But if you run that to its logical conclusion, what does it mean, if we don’t have deliverables this time around?”

The draft also includes a target for five new neighborhood greenways, a modest goal that reflects a reality that most neighborhoods have already had their greenways established by this point, 12 years after Seattle’s first one was rolled out in Wallingford. What the next levy could fund is greater investments in those neighborhood greenways, including traffic diverters, and extensions to community amenities. But when it comes to on-street bike facilities directly connecting Seattle residents with business districts and routes to downtown, the consensus is that the next levy needs to heavily lean on making improvements in the South End.

“The big opportunity that we see with this levy is righting this his inequitably developed bike network,” Clark said. “The last levy, it was really heavy on North [Seattle] and Downtown bike infrastructure projects, which — some of them got shelved, a lot of them got done, and they’ve fundamentally changed, certainly how I get around the north end, and Downtown, right? And so how can we make sure that this levy does the same for the rest of the city?”

“One of the things that we think about is the miles of contiguous bike lane throughout Seattle,” Cascade’s Seattle policy manager Tyler Vasquez said, highlighting the value of filling in gaps. Vasquez pointed to the city’s high injury network map, the streets that see the highest numbers of fatalities and serious injuries. “We look at the injury network, and we look at where those streets lie, and we’re seeing that there needs to be an investment in Southeast Seattle or South Seattle.”

Cascade is pushing for the final levy to include an additional $20 million for bike infrastructure, and is specifically urging investments in the South End.

“We can’t have a levy without a target,” Clarke said. “If we’re asking voters to approve something, then it needs to be clear what exactly they’re approving.”

But Clarke wants the city to start thinking differently about how it measures the expansion of the city’s bike network network. “I think the miles target is nice in a lot of different ways. Does it meet the needs of where we’re at now? Does it get to what we ultimately want, which is a bike network that connects communities, connects neighborhoods all across the city — just miles alone doesn’t get to the geographic aspect.”

This transportation levy represents the first major opportunity that the Harrell Administration has to actually put forward its concrete vision for the future of the city’s transportation system, as it has mostly spent its first few years delivering projects that were started under previous administrations and focusing on finishing Move Seattle’s era strong. As the proposal heads toward voters, it’s clear that more details need to be fleshed out to actually be able to hold the administration — and future ones — accountable for its own commitments.

Take Action

At 2pm Saturday April 20, a coalition of advocacy groups (which includes The Urbanist) are hosting a “Transportation and Housing Rally for a Healthy Future” at Jimi Hendrix Park. [Note: The Urbanist’s advocacy staff and volunteers participate in coalitions independently of our editorial team.] In honor of Earth Day, organizers want to push for more housing and better transportation in the levy and the Seattle Comprehensive Plan. Bike groups are also organizing two group rides to the event from West Seattle and Ballard, respectively. Details here.

Weigh in via SDOT’s online engagement hub until April 26.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.