Give feedback and ask the City questions to push for a better plan to address the housing crisis.

Seattle released its draft “One Seattle” Comprehensive Plan last week to much disappointment and criticism by urbanists and housing advocates. The plan is both astounding and confounding in its complacency and lack of bold vision.

Headlines such as “Harrell Throws in the Towel,” “Seattle Releases Comprehensive Plan Less Ambitious Than Bellevue,” and “Harrell’s Anemic Growth Plan Is Not ‘Space Needle Thinking’” capture the feeling. And both the Seattle Planning Commission and the head of the City Council Land Use Committee seem to agree.

Despite being a year overdue, the proposal somehow manages to put off a number of hard decisions and push many important details into future planning processes regarding zoning changes and neighborhood plan updates for the city’s seven largest growth centers (as if in an effort to win by exhausting us all with process).

Our city has experienced nearly two decades of extreme rises in rent and housing prices as our city has seen an almost continuous boom in population and jobs fueled by a strong tech sector. Yet the plan suggests that the folks at the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) and the Mayor’s office seem to think that everything is fine — it’s as if they all bought houses in 1989. But we can all see it’s not and this is why the majority of public comments during the scoping phase asked for the maximum housing supply option only to be blatantly ignored by the Harrell administration.

But what would a better version look like? What should we tell the city to change so we salvage the mayor’s small ball plan? Below are six ways to bring the plan closer to what we need — starting with an abridged summary for those chomping at the bit to submit their feedback now.

- Allow bigger buildings in more places to break out of the “Urban Village” strategy and scarcity mindset.

- Add more “Neighborhood Centers” to anchor small neighborhood business districts with housing.

- Zone for fourplexes and sixplexes that will actually get built and support families with three- and four-bedroom homes. The proposed restrictive size limits — particularly the floor area ratio (FAR) set at a measly 0.9 — are effectively erasing the value of the fourplex and sixplex zoning. Follow state model code and allow 1.6 FAR in sixplex areas instead.

- Embrace transit-oriented development and allow larger apartment and condo buildings near all frequent transit corridors. The mayor’s proposal appears to have jettisoned the transit corridor alternative from scoping.

- Remove parking requirements. Parking requirements are a secret tax on housing that render many projects infeasible. We cannot afford this amidst a housing crisis.

- Corner stores should not only be on corners. Allow more flexibility to ensure more neighborhoods can actually get a bodega or cafe.

1. Allow Bigger Buildings in More Places

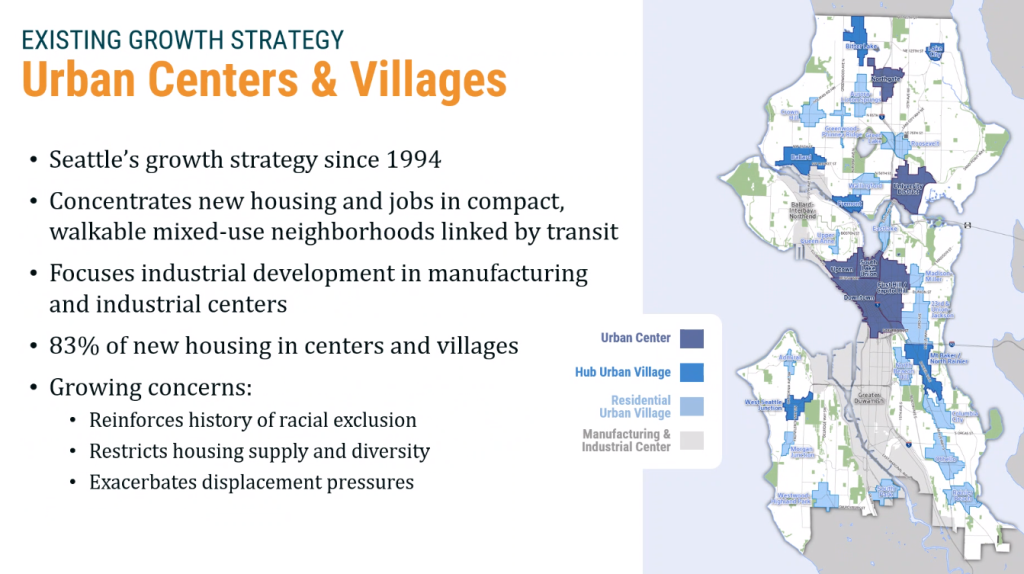

Mayor Bruce Harrell’s draft Comprehensive Plan sticks with the “Urban Village Strategy,” which both has many problems and produced much of Seattle’s new housing. They are doing close to the minimum to expand upon it, despite choosing to take urban villages and rename them “Urban Centers.” The plan has one new “Urban Center” at 130th Street around the new Link light rail station, and they expand several of the most ridiculously shaped ones to encompass something closer to a 15-minute walkshed. As for capacity within Urban Centers, OPCD proposes to upzone Residential Small Lot (RSL) zones to Lowrise 1 (LR1), but otherwise leave them as is.

Urban Centers can and should continue to be anchors within a broadened growth strategy. This means more Centers in places such as Magnolia, Sand Point, and around the soon to open NE 145th Street Link station. Expanding existing centers to incorporate their full walkshed as proposed and that of Link stations (I’m looking at you Montlake) and generally erode the hard boundaries – see below.

There also needs to be talk of greater increases in zoned capacity as part of this process within existing Centers than OPCD proposes. As of today, there are townhouses getting built a block from light rail stations because that is what zoning allows, squandering our region’s multi-billion-dollar investment in transit and wasting capacity for new housing. The city needs to change that.

2. Add more neighborhood centers

The original proposal for neighborhood centers or “anchors” in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) scoping document identified 42 locations. This has been reduced in the draft to 24 (plus the Urban Center at 130th Street replaced two anchors). Architect Dylan Glosecki has done a survey of existing small neighborhood centers and mapped over 80 that already exist throughout the city. If we want a 15-minute city that supports people being able to walk, roll, and bike for their basic needs then there must be goods and services available near people’s homes. Neighborhood centers and corner stores are how we make it happen.

Tell the city to restore the excluded centers in place such as Seward Park, Magnolia, Hillman City, and the multiple centers that disappeared in Northeast Seattle. In addition we need to tell OPCD to make these significantly larger than the proposed three-minute walkshed. Many of the existing centers are already larger than this and should be included. And if we want to make viable centers that can support the services residents want we need to provide the space and the people to make them viable.

3. Make missing middle work for more housing in more places

The most exciting part of the plan is the neighborhood residential zoning and it is only happening because the state is making the city do it and even then the author of the bill is questioning if the city is meeting the law’s minimum requirements. The state law requires cities like Seattle to allow four homes on all lots and six on lots that are near transit or provide two affordable homes on-site. But as always, the devil is in the details.

One interesting byproduct of this process is the city produced a study of missing middle housing types that are being built in Seattle today to show how they would work under the new zoning. Unfortunately, they stopped there and failed to imagine a future that does not look like today. They ignored small apartment buildings (except for affordable projects), rooming houses, stacked flat condos, and any new to Seattle housing form (or in many cases types that existed decades ago but have been outlawed).

The rules the Harrel administration proposed work to preclude these forms by limiting the allowable development capacity to much less than what the state model code would require. The state proposes a floor area ratio of 1.2 for fourplexes and 1.6 for sixplexes, which Seattle at the very least should match. Instead the City is proposing a ratio of 0.9 across the board, which will stunt development and force units with fewer bedrooms. The current disparity means the state is proposing 80% more housing space than Seattle on sixplex lots. Our progressive city fails to be as forward thinking as the Washington Department of Commerce.

Tell the city it needs to match or exceed the state floor area minimums and allow more housing, taller housing, and greater lot coverage. This will allow for more housing diversity in more places, more housing for families, more housing for singles, and what we really need, which is more of everything.

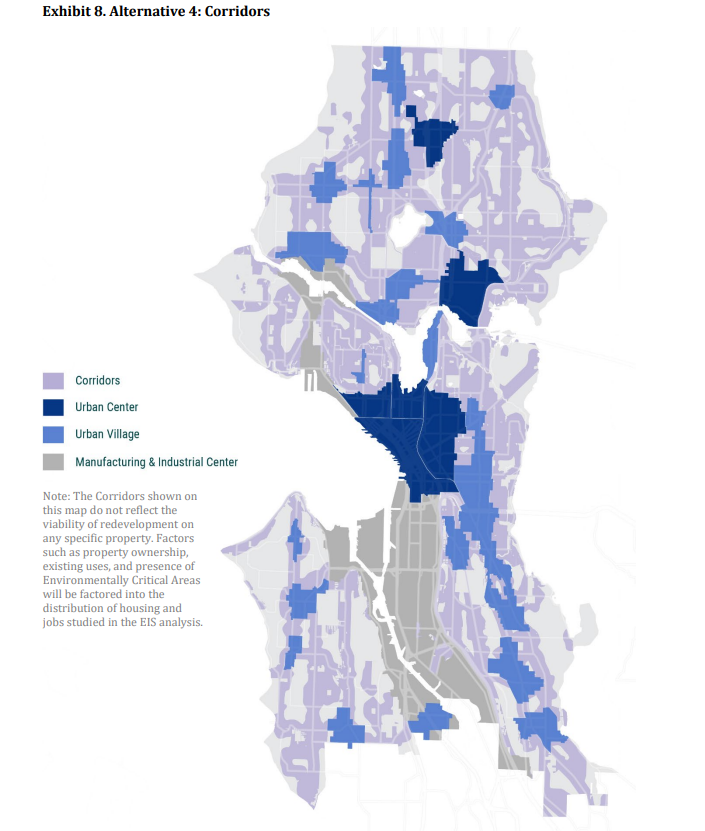

4. Pretend the State had passed the transit-oriented development bill

Seattle planners and politicians like to pretend our city is a visionary leader in urban planning. But it isn’t. On a national scale we lag many other cities, and when looking beyond our national borders we aren’t even in the game. Most of the innovation in this plan and most changes that have made housing easier to build in Seattle have been forced on it by the state. There has been a proposed transit-oriented development (TOD) bill proposed in the legislature the last two sessions that failed. But momentum is building and a TOD bill will pass eventually.

The scoping document included upzones near transit corridors in Alternative 4 and 5 and the growth strategy says they may include them. This again needs to be the baseline for the plan, not a squishy maybe. This could be Seattle’s chance to stop waiting for the state to force us to make the right choice and instead be a leader and show what good transit related zoning looks like.

So tell OPCD to include all the high capacity transit routes that exist and are planned. Include a wide corridor that allows for new housing not just hugging the busy road but for multiple blocks on either side. Make apartments and corner stores viable within the entire zone. Connect urban villages with dense corridors that can provide additional services to adjacent neighborhoods. Pretend for a moment that we believe in a future where transit is the best way to travel and plan for it.

5. Remove parking requirements

Can Seattle, which talks up its climate commitments, progressive policies, and efforts to make housing more affordable do something as basic as removing antiquated parking mandates? It is already an embarrassment that we still have them when such cities as Buffalo, Raleigh, Austin, Minneapolis, and Port Townsend don’t. The closest the One Seattle Plan comes is saying in the Neighborhood Residential Concept document that they *may* consider removing them. If no one objects. Or it doesn’t make the mayor and council too nervous. The visualizations accompanying the proposal all show parking next to multiplexes and corner stores, signaling the drift at city hall.

Let’s tell the mayor that if the city cares about climate change and housing affordability, this should not be an open question, it should be the plan. The city must remove parking requirements city wide.

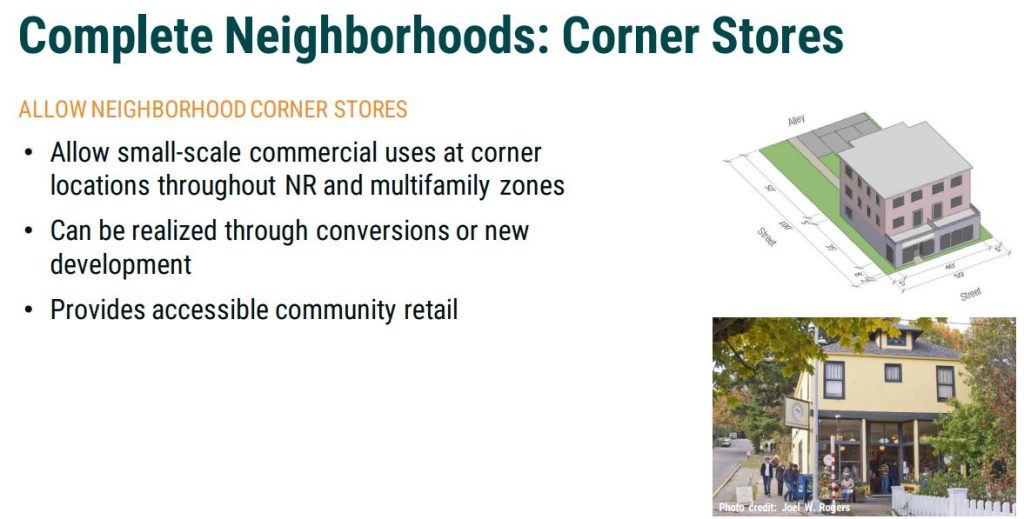

6. Corner stores should not be only on corners.

Another of the more positive aspects of the plan is that it *may* allow corner stores. But only at corners. And only some uses. Home based businesses are a good thing. More neighborhood services are a good thing. And if they are good for our city they are good not just on corners. Many of the poster children for corner stores such as Yonder Cider and Seven Coffee Roaster are not on corners. Limiting this to corners will restrict it to the point where it may end up being mostly theoretical.

So let’s tell OPCD to allow small scale businesses in all zones including small cafes, stores, services, and even small scale production. Let’s let it happen on any part of the block, not just the most expensive corner lots. Let’s create space for people to become entrepreneurs in their own houses (which opens the possibility to lower income folks), to grow the next great company in their garage or front room, for neighborhoods to gain new amenities that benefit residents (who wouldn’t love to be able to get a pupusa or a cup of teas in their neighborhood?), and to unleash the creativity of our residents.

Three questions for OPCD

If the six ways to improve the plan wasn’t enough for you, here are three questions to ask OPCD and the mayor’s office when you talk to them at an open house:

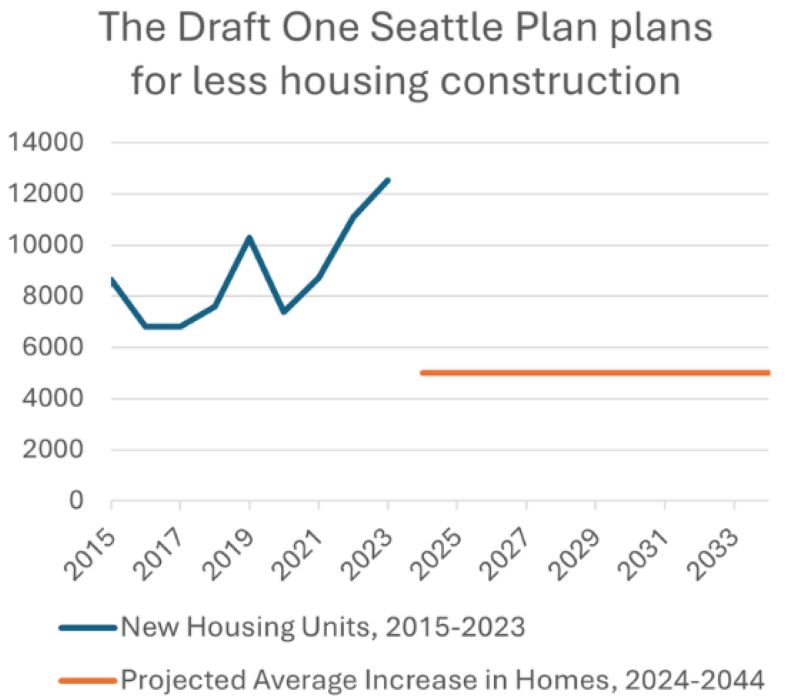

1. Why are your growth targets so low?

After under estimating the amount of growth and where it will occur for years, OPCD again claims that they have it right this time and the city will grow less than trend all the while ignoring the huge housing deficit we have built up over the years. We are in a crisis, let’s act like it.

Planners seem to have core principle to plan for exactly as much housing as they forecast and not a single home more. This is wrong. This has resulted in housing scarcity and price increases, a run up in multifamily land value, and intense development in the limited areas where it is allowed. Creating a large buffer of zoned capacity can result in lower land cost, which means it’s cheaper to build new homes, and more gradual change throughout the city. Tell OPCD to plan for housing abundance and growth, not for exclusion and displacement as they are now.

2. Is equitable development served by providing less housing in areas of high displacement?

Displacement has been happening for decades in communities of color, such as the Central District and Rainier Valley and many other parts of the city. The city’s plan to minimize displacement is to provide less development capacity in these areas. This is a continuation of the same strategy that has led to $800,000 townhouses a block from Link stations in the name of anti-displacement, which seems like an outcome where almost everyone loses.

The problem with this strategy is that the bulk of evidence shows that new housing reduces the pressure on existing residents by absorbing the demand. So less housing could lead to more displacement as housing values rise and flipping existing houses becomes more profitable. The mayor’s plan does not pair pulling back on housing capacity in displacement-risk areas with significantly increasing capacity in low-displacement-risk areas. Thus, the fundamental shortage of homes remains.

But the most concerning aspect is that the strategy essentially restricts Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) landowner access to increased land value in the form of the greater development capacity that the city is providing to whiter neighborhoods. It is denying BIPOC communities an opportunity to gain wealth from their property while also limiting opportunities for people who have already been pushed out of the neighborhood to return. This paternal response by the city continues the pattern that stripped land value in Black and brown neighborhoods in the first place through redlining and other discriminatory processes. Many white families have been able to use the value of their home as a piggy bank for capital to start a business or to pay for improvements or to retire. Homeowners of color should at least have equal opportunities.

3. What’s the point of public engagement if you ignore it?

The city already asked what we thought during the EIS scoping process and got a resounding answer to go big! Share the Cities analyzed the comments received during the scoping phase and found that over 60% wanted Alternative 5 (all of the above) or a bolder growth strategy, such as the grassroots Alternative 6. But instead of five or bolder we got five lite. It’s as if OPCD and mayor’s office have their own idea of what the public wants and it is not the same as what the public has told them repeatedly. So be sure to ask OPCD this questions while reiterating what we told them before – more types of houses in more places affordable to more people. Or as Share the Cities has put it, four floors and a corner store everywhere.

Let them know what you think

And there are plenty of opportunities to tell them how to improve the plan and ask questions both via the online Engagement Hub, by emailing OPCD, or by attending upcoming public meetings:

- Wednesday, April 3 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Chief Sealth International High School, 2601 SW Thistle St, Seattle, WA 98106 - Tuesday, April 16 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Garfield Community Center, 2323 E Cherry St, Seattle, WA 98122 - Thursday, April 25 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm

Eckstein Middle School, 3003 NE 75th St, Seattle, WA 98115 - Tuesday, April 30 – 6:00pm – 7:30pm –

McClure Middle School, 1915 1st Avenue W, Seattle, WA 98119 - Thursday, May 2 – 6:00 p.m. – 7:30 p.m.

Virtual Online Meeting, link to be provided at a future date

Ultimately when all is said and done, the fate of the plan rests with our electeds who must approve it, so it is also important that you call or email the Mayor, and City Council and share your thoughts. Many of them seem like they have a strong status quo bias, but they also have a strong get re-elected bias. If enough people reach out we may just be able to save the city from its governments own worst instincts.

Patrick grew up across the Puget Sound from Seattle and used to skip school to come hang out in the city. He is an designer at a small architecture firm with a strong focus on urban infill housing. He is passionate about design, housing affordability, biking, and what makes cities so magical. He works to advocate for abundant and diverse housing options and for a city that is a joy for people on bikes and foot. He and his family live in the Othello neighborhood.