Nearly two years after launching its latest safety project focused on Aurora Avenue N, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is just getting into presenting the real tradeoffs inherent in reallocating space along the city’s most dangerous state highway. The need for urgency couldn’t be higher: in 2023 alone, two people were killed in traffic crashes on Aurora, and at least another 160 people were injured, with at least 15 of them suffering serious, long-term injuries. Every month of additional study and analysis leads to more people getting hurt.

Prompting this work was a 2021 state grant that provided funding for initial planning on a corridor study, but things were kicked into high gear with the promise of a $50 million dollar award from the Washington legislature to fund safety improvements in 2022’s Move Ahead Washington transportation package. Initially, the legislature clearly tried to push the City of Seattle to quickly design improvements along one stretch of Aurora to make quick safety gains. The 2022 law stipulated that the new design should be complete by fall of 2023, a likely unrealistic initial deadline but one clearly intended to get the City to move fast.

Then the Seattle Process took over, and the scope for the initial Aurora study was kept broad, looking at the entire corridor from South Lake Union north to the city line, and other agencies including King County Metro and Seattle Public Utilities were brought on board. The timeline for the full $50 million award became opaque. Meanwhile, people are still getting hurt and killed along Aurora.

In the meantime, SDOT has completed a “top to bottom” review of its Vision Zero program, with a forthcoming Vision Zero implementation plan set to arrive this spring. While the review appears to have provided positive momentum for some concrete actions — like the broader roll out of no-turn-on-red restrictions on streets like Aurora — the timing of the overall Aurora Avenue project provides an immense opportunity to make safety gains. Plus, it represents an essential test for the entire Vision Zero program in Seattle, which faces its 10-year anniversary next year.

Modeled off successful Vision Zero campaigns that started in Sweden and spread across Europe and then the world, Seattle’s 2015 pledge, aimed to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injury crashes by 2030, but they have remained stubbornly high.

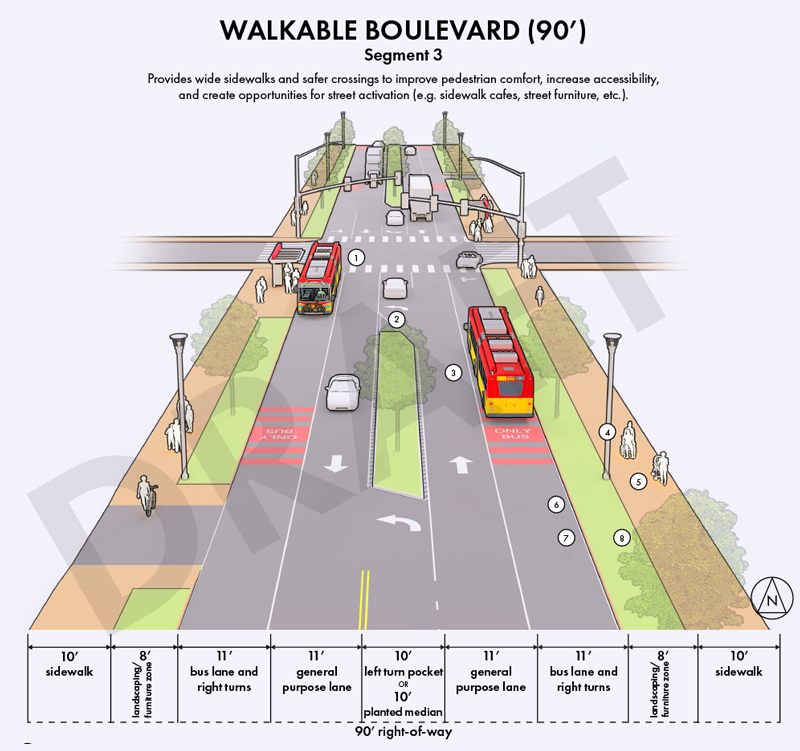

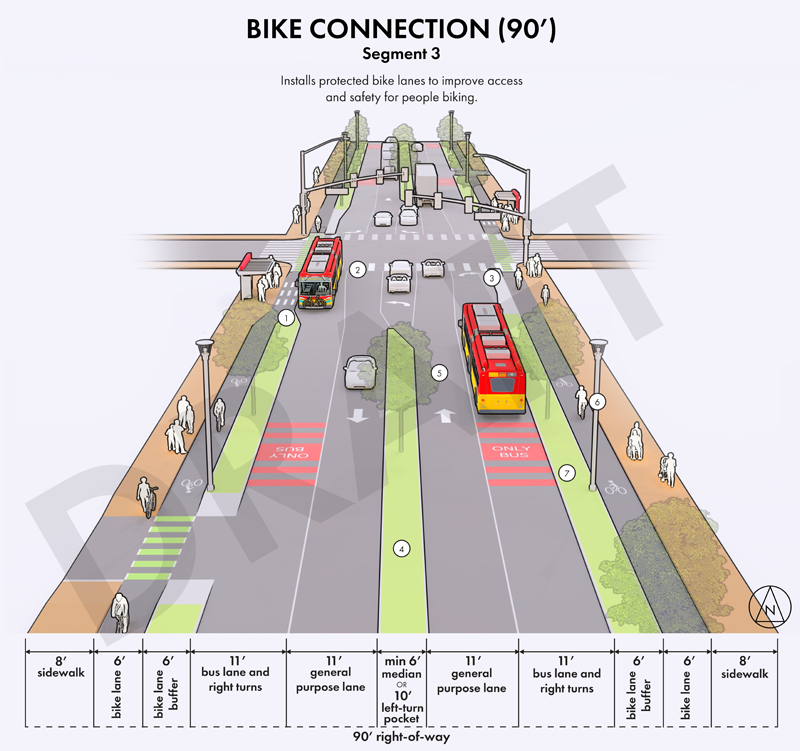

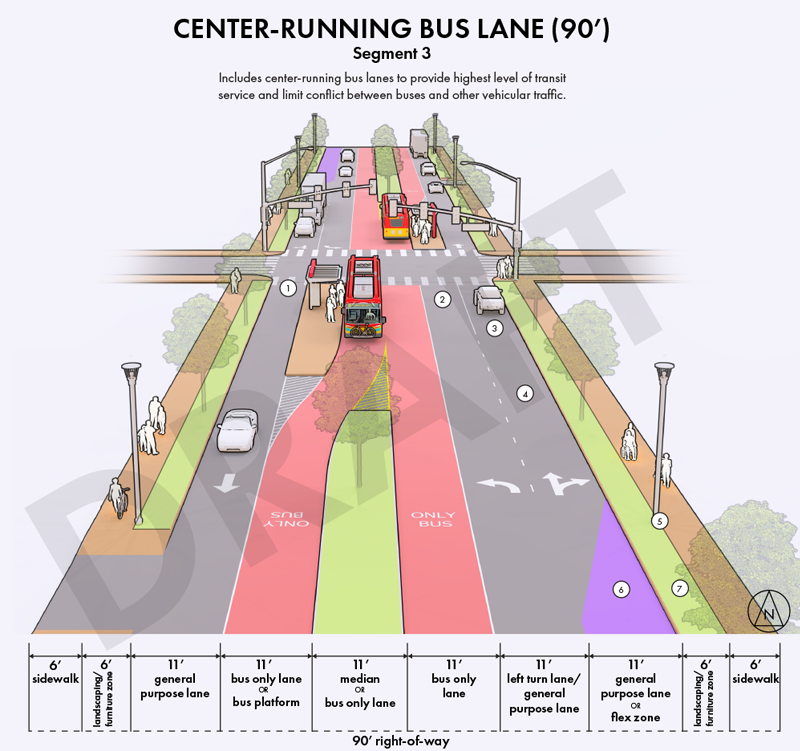

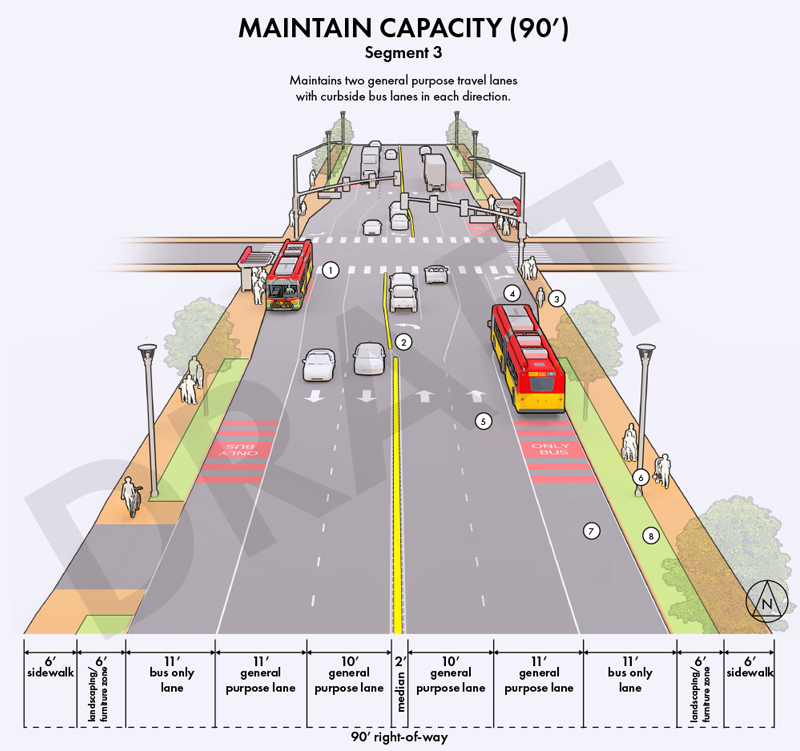

The four concepts that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) released earlier this month illustrate how Aurora might be changed, but they aren’t actually real yet. They haven’t actually been put through the ringer when it comes to feasibility. And as others have pointed out, they pit numerous modes that we’d all like to prioritize on the street — walking, biking, transit, freight — against each other while at the same time providing an option that maintains the status quo, which we know is untenable.

Since the release of the top-to-bottom Vision Zero review, the city has already experienced a significant, high-profile missed opportunity, in its planned repaving of Denny Way between Seattle Center and I-5, a prominent street on Seattle’s high crash corridor network. Against the recommendation of City staff, who correctly identified a “large opportunity” to rethink how that four-lane road through the city’s most dense neighborhoods operates now and in the future, the project will be moving forward with very few substantive modifications to how Denny Way operates. The fast timeline to take advantage of federal dollars is, at least partially, taking the blame here, something that can’t be said about Aurora.

But a bad starting point for creating an Aurora Avenue that truly embraces a Safe Systems approach is deciding which modes the street simply doesn’t have any room for. Even before the technical analysis has been released, voices are calling for safe space for people biking along Aurora to be taken out of the plans, with people on bikes diverted to parallel side streets.

“The greenways, the bicycle greenways have worked really, really well,” Stanley Ryter, the co-chair of Seattle’s freight advisory board said earlier this month after getting a briefing on the plans. “Incorporating bike lanes on Aurora just doesn’t really seem like a good idea.”

People currently bike on Aurora: in the bus lanes, on the sidewalks where they exist, on the shoulders where they don’t. The question isn’t the cost of including them, but the cost of not including them. And a street that is 90 feet wide, space is definitely available for all modes, especially if the priority is ensuring safety and not maximizing throughput.

Aurora Avenue is one segment of State Route 99, which exists as a barrier and a public health issue in communities north into Snohomish County and south into South King County. WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar has recently begun highlighting the significant problems posed by surface highways that run through population centers. “That’s where people are getting killed,” Millar said early this year at a regional policy meeting. “That’s where people are getting seriously injured…what are we doing about that as a safety initiative?”

Washington has around 1,100 miles of such highways, which see a fatal crash rate that is twice as high and a serious injury crash rate that is three times as high as other types of roadways across the state. A complete streets mandate approved by the legislature in 2022 is set to make improvements to these types of streets as individual maintenance projects move forward, but Seattle has a chance to go further and set the standard for what a surface-running state highway through multiple population centers can look like. But to do that, it will need to overcome significant voices of opposition, many of which haven’t even begun to speak up yet.

The proposals for Aurora Avenue that get advanced after this point need to center safety in a substantial and meaningful way, and if they do not, Seattle will likely have to relinquish any claims to being a Vision Zero city.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.