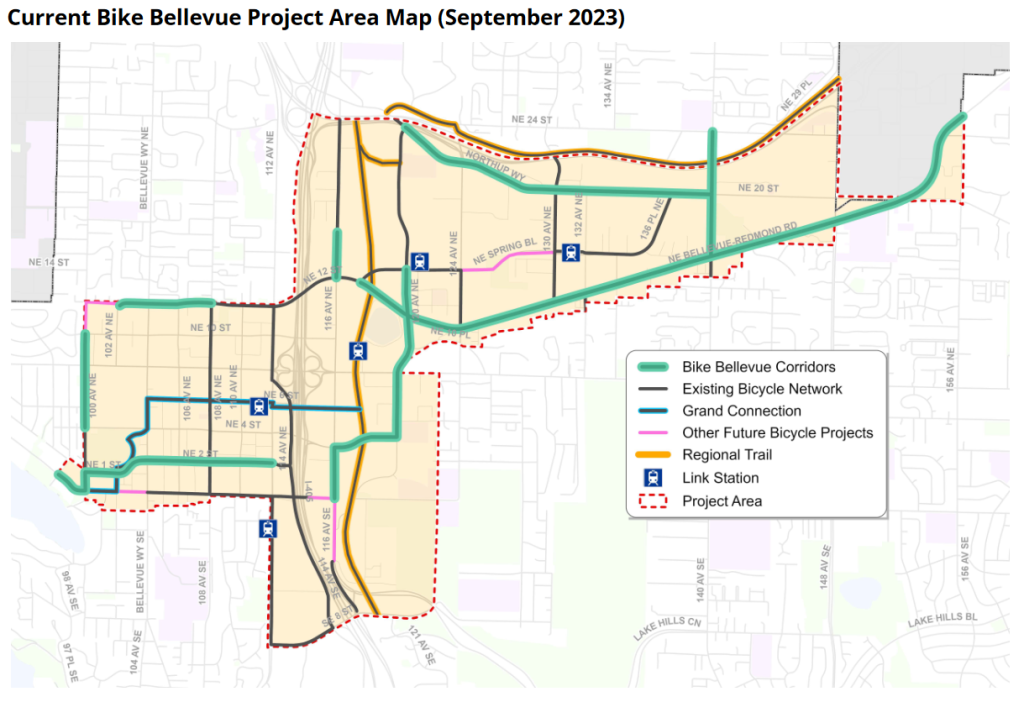

On Monday night, the Bellevue City Council dealt a significant blow to efforts to complete a fully connected on-street bicycle network in central Bellevue, with most councilmembers vocally distancing themselves from the recommended network of 11 corridors in the Downtown, Wilburton, and BelRed neighborhoods that the city’s transportation department put forward last year. That network, called Bike Bellevue, was intended to improve safety on some of Bellevue’s most dangerous streets while at the same time providing a full network that doesn’t strand riders on unconnected facilities.

But after hearing significant opposition from business interest groups and residents who didn’t want to see general purpose travel lanes reallocated to make room for bicycle facilities, the Council failed to stand by the overall proposed network. Multiple members raised significant concerns of their own about reallocating street space from drivers.

While the body stopped short of taking vehicle lane reallocation for Bike Bellevue off the table entirely, they voted, nearly unanimously, to only consider it as a “last resort” and approved a framework that will allow Bellevue’s transportation commission to de-prioritize — or even discard entirely — routes that take space away from cars. It will fall to the transportation commission (an unelected body composed of seven members appointed by the mayor) to do the work to pick apart the Bike Bellevue network, finishing the job for the city council.

Monday’s meeting was the first presentation on Bike Bellevue that the city council had received without Franz Loewenherz, the city’s Mobility Planning and Solutions Manager who had been shepherding the project forward until late last year. Loewenherz was removed from the project in December after an ethics complaint was filed against him for sharing public information on Bike Bellevue with a group of journalists and advocates, a complaint that was tossed out within a matter of weeks.

But city officials including City Manager Diane Carlson and Transportation Director Andrew Singelakis declined to reinstate him as head of the project, and on Monday, Singelakis and Deputy Transportation Director Paula Stevens spent virtually no time defending the full Bike Bellevue corridor network and the work staff did to get to this point.

“When the draft concept guide came out, it was pretty apparent that many of the 11 corridors involve the removal of vehicular travel lane for bike lanes,” Singelakis said. “And this really generated quite a bit of significant public interest: many people in support, many people in opposition. And given the interest, we really felt the need to bring this back to council for an update and further direction.”

There was near unanimity Monday that Bellevue should not reallocate street space for bike lanes along busy Bel-Red Road, despite it being one of the most dangerous streets in the city and three of the 11 corridors including some portion of it. Mayor Lynne Robinson, who touted her status as a 10-year bike commuter, suggested that the City should instead ask developers to utilize their properties to create separated bike lanes as they construct projects along the corridor, a process that would likely take decades to produce contiguous segments, if at all.

Bellevue has $4.5 million currently allocated for bike network upgrades, only around a quarter of the $18.5 million currently estimated to be needed to implement all 11 of the planned corridors. But following Monday night’s meeting, direction from the city council was pretty clear that the most important corridors to implement are the ones that won’t require taking any travel lanes, regardless of what best practices and crash data actually suggests about which routes will be most impactful or produce the biggest reduction in serious or fatal injuries.

Bellevue’s fairly ambitious growth plans, which concentrate a significant amount of planned housing and jobs in the same neighborhoods Bike Bellevue would serve and which anticipate an increase in the city’s population of at least 65% by 2044, clearly call for new approaches to transportation. But the Bike Bellevue plan represents a clash between the faction of city interests who simply can’t imagine reallocating any current space available to drivers given those significant expected population increases and the faction that simply can’t imagine continuing the status quo.

Mostly missing from the conversation Monday night were the experiences of current cyclists who will continue to use the Bike Bellevue corridors to access destinations in Bellevue, or the ancillary benefits that would come from bike infrastructure including improved pedestrian safety and calmer streets.

City councilmembers were apparently not persuaded by data compiled by their city’s transportation department that showed full implementation of the 11 Bike Bellevue corridors would only impact drivers to the tune of 0.2 miles per hour, on average, while at the same time be estimated to prevent between four and eight serious injury or fatal bicycle crashes over the next 20 years. Nor were most ready to point to examples of instances where the City of Bellevue has already reallocated street space to make space for bike infrastructure, like along 108th Avenue NE in the heart of Downtown Bellevue.

“As a lifelong cyclist myself, who deeply wants to see more bike facilities in our community, I don’t think the removal of a lane necessarily meets our goals of providing a safe and comfortable experience for the rider,” Councilmember Jared Nieuwenhuis said. “Paint and post is not protected, and I’ve got grave concerns about some of the safety of cyclists in our community because of it, especially on Bel-Red.”

Without any space created, people biking will likely continue to bike along Bel-Red’s sidewalk, not necessarily a safety improvement.

Nieuwenhuis put forward a motion that would have added language explicitly prohibiting travel lane removal from Bike Bellevue’s principles, but a majority of his colleagues stopped short of supporting that position.

“I think the priority should be: come up with a solution that provides a very safe bike lane that doesn’t need any repurposing [of] travel lanes,” Bellevue’s Deputy Mayor Mo Malakoutian said. “Removing [a] traffic road lane should be our last, last, last approach, especially in BelRed, again, [with] the amount of density that we’re bringing there […] I don’t even know how our current road capacity will manage that density.”

That “last resort” line and the reticence to proactively improve street safety it betrayed did not sit well with King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, a former Bellevue mayor who had hoped to benefit from the safer network. “As I biked in speeding traffic and on sidewalks (the red parts) from home to downtown Bellevue today, I found myself wondering what my new council member meant when he proposed bike lanes be “a last resort” if car lanes are impacted. Maybe that means after I am hit?” Balducci tweeted along with a map of her route.

As I biked in speeding traffic and on sidewalks (the red parts) from home to downtown Bellevue today, I found myself wondering what my new council member meant when he proposed bike lanes be “a last resort” if car lanes are impacted. Maybe that means after I am hit? #VisionZero pic.twitter.com/TH7JlMC9G2

— Claudia Balducci (@KccClaudia) March 26, 2024

Out of the seven councilmembers, it was Janice Zahn who defended the Bike Bellevue plan the most Monday night, expressing reluctance to eliminate any corridors that correspond with segments of the city’s high injury crash network. Data from that network was used to directly inform the Bike Bellevue network in the first place. Zahn also was a lone voice in expressing a willingness to try out pilot projects that do take away existing travel lanes. “We should be willing to pilot these pieces of creating that connected corridor and see how it works, and absolutely collect the data,” she said. “Many cities around the country have already implemented this, they have data themselves. We have some data ourselves on our roads.”

The Bike Bellevue plan was a natural next phase in the evolution of the city’s bicycle network, building on the “vision zero” road safety plan that the city adopted in 2020. But Bellevue’s powerbrokers quickly made the reallocation of existing vehicle lanes a red line after the full Bike Bellevue design concepts were released in November and included 5.9 miles of planned travel lane conversions along with 30 parking stalls that would have to be removed.

“We understand and appreciate the value of a multimodal transportation network that is user-friendly and safe. At the same time, we envision connectivity in Bellevue that is proportionately designed to support existing and projected use, and which does not interfere with vehicular capacity that the vast majority of Bellevue residents and workers depend on for mobility,” read a joint letter sent this week, signed by representatives of real estate groups including Kemper Development, Wallace Properties, and the Vander Hoek Corporation. That group proposed an alternate framework to the city that wouldn’t result in “crippling the arterial road network” in Bellevue, and included eliminating seven of the 11 corridors and redesigning the rest.

City staff Monday night confirmed they’ll be taking a look at that alternative network. “I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that this is some additional information that we want our transportation commission to take a look at,” Stevens said of the alternative map, which would include no other east-west connection between the BelRed neighborhood and the Spring District except for the expensive planned off-street connection that the city is designing along Spring Boulevard: all other bike riders looking for a safe connection would be directed to the hilly 520 trail on the north side of the state highway.

Advocates for Bike Bellevue Monday asked the council to keep Bike Bellevue whole, an ask that was ultimately in vain.

“We are hoping that tonight’s discussion provides clear direction to the [transportation] commission and empowers staff to do what they are trained to do: use engineering best practices to make our streets safer,” Gina Kavesh, Bellevue resident and co-president of Cascade Bicycle Club’s board said in public testimony. “After all, this isn’t theoretical, it’s about people, regardless of how we get around, being able to do so safely.”

In the end, that direction was very clear, but came with some big asterisks when it comes to making Bellevue’s streets safer for everyone.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.