Councilmembers also floated the option of lowering police officer standards to hire more cops, faster.

After again failing to recruit faster than it lost officers last year, the Seattle Police Department (SPD) is in the middle of a complete image rehaul and rebrand. Watch a recent recruitment video, and you’ll see diverse officers in uniform shaking people’s hands, petting dogs, and even hugging people. In these videos everyone is smiling, and Seattle is uncharacteristically sunny. Not shown? The mocking tombstone in an SPD breakroom, the laughter of Officer Daniel Auderer, the Vice President of the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG), over the death of Jaahnavi Kandula, or scenes of violence against peaceful protesters in the streets in 2020.

Last Tuesday Seattle City Council’s public safety committee met to discuss SPD’s recruitment and retention. Police Chief Adrian Diaz has been vocal in stating that SPD has lost 725 officers over the last 5 years, amounting to turnover of half of the force. The department is still down 375 officers, employing 913 fully trained and deployable officers at the beginning of this year. Instead of using this staffing issue as an opportunity to rethink the size and role of SPD in the community, Mayor Harrell has stood firm in his goal of needing 1,400 officers.

The Council’s desperation to meet that goal was palpable last Tuesday, with several councilmembers (including one, Councilmember Maritza Rivera, who doesn’t even sit on the committee) repeating one another while falling over themselves to offer SPD any and everything it could need to hire more officers.

Chief Diaz said SPD hopes to hire 125 new officers in 2024; there is space for about 84 rookies in the police training academy for the year, which means to hit his goal, SPD would have to make 41 lateral hires from other police departments. Last year SPD only managed to hire 61 new officers, and as of the end of September 2023, only six of those hires were laterals, meaning its current staffing goals range from deeply optimistic to unrealistic. While staffing trends weren’t as dire as previous years, SPD still experienced a net loss of 36 officers in 2023.

What budget deficit?

The low hiring numbers for 2023 were in spite of hiring bonuses for new officers passed by the Seattle City Council in 2022: $7,500 for new recruits and $30,000 for lateral hires from other departments. A 2019 report conducted by the city found only 20% of officers said the hiring bonus was a factor in their decision to sign on, while also finding hiring bonuses could be demoralizing to existing personnel.

However, at the recent State of Downtown event hosted by the Downtown Seattle Association, Chief Diaz dodged the question about whether these bonuses work, saying, “If other departments are enhancing with incentives and bonuses, we have to be able to do that same stuff for our department.” The Seattle Times cited a recent report analyzing the program that said, “It is impossible to pinpoint the hiring incentive’s specific effect with the available data.”

Among new incentives discussed for officers were take home cars, tuition reimbursement, a Master of Police Officer program, and child care. But perhaps most striking was the repeated discussion of housing subsidies for officers only a week after the Mayor’s Comprehensive Plan proposal was unveiled that fails to deliver solutions to provide sufficient affordable and workforce housing in the city.

In counterpoint to councilmembers’ enthusiasm for housing subsidies, The Stranger reported that “paying for cop housing hasn’t seen success in other jurisdictions,” citing programs in Baltimore and Los Angeles.

To listen to the conversation between councilmembers and SPD staff, you wouldn’t think the city is facing a $230 million budget deficit that needs to be addressed this fall. In spite of a hiring freeze (that omits SPD and the fire department), city departments are being asked to make plans for cuts and bracing themselves for potential layoffs. Most councilmembers have been leery of supporting any new revenue sources in spite of recent admissions that a full audit of the city budget will be impossible this year.

Councilmember Bob Kettle, who chairs the public safety committee, is eyeing the JumpStart tax revenues to plug the budget gap, Crosscut reported; JumpStart currently is the largest funding source for affordable housing in Seattle. Reallocating funds away from its spending plan would result in defunding Seattle’s efforts to build more affordable housing.

And yet, when it comes to SPD, apparently the sky’s the limit when it comes to allocating new funds. In 2024 SPD’s budget consumes about 23% of the city’s general fund, and that percentage is expected to grow after the approval of the new SPOG contract anticipated shortly. The new contract will almost certainly give officers a significant raise as well as back pay for the last few years.

A price tag has not yet been given for all the discussed officer incentives, nor has the Council seemed particularly interested in keeping SPD spending in check in spite of the austerity being felt by many other departments.

Lowering hiring standards, but quietly

Also presenting at the meeting on Tuesday was Andrea Scheele, the executive director of the Public Safety Civil Service Commision (PSCSC), who oversees the testing process undergone by SPD officer candidates. Councilmembers were harsh in their assessment that Scheele needed to come up with a better plan to streamline the testing process to make SPD more competitive, with Councilmember Cathy Moore insisting she return to the committee in 30 days time to share concrete steps taken beyond asking for an additional staff member. This was in spite of the PSCSC recently cutting the time in half that candidates who fail the exam have to wait to retake it, from six months to three.

Meanwhile, candidates who fail the physical agility test are now able to receive additional training and take it multiple times in order to pass.

But councilmembers are interested in potentially changing the main test that candidates take in order to get a higher pass rate. The test used right now from the National Testing Network has a 60-65% pass rate. After being placed under the consent decree, Seattle’s priority was to use a test that was tailored to assess cognitive abilities, judgment, and ethics of a potential police officer. In contrast, the other possible test, the Public Safety Test, has a 90% pass rate according to the Seattle Times.

When pressed, Director Scheele said, “If the City is interested in changing its hiring standards or its testing standards, we should have that conversation.” In response to such direct pushback, Council President Sara Nelson insisted they were talking about processes and bureaucracy, not standards. But the inconvenient truth is that switching tests to one with a higher pass rate might indeed lower standards and lead to less qualified officers or even officers more prone to bias, something that is already a large problem for SPD.

What about female officers?

SPD is touting their participation in the 30×30 initiative, which has a goal of having 30% of officers be women by 2030. However, in 2023, only five new hires were women. Strikingly missing from this conversation on Tuesday was a discussion of the report SPD commissioned last year as part of 30×30, which documented the sexual harassment and discrimination faced by women officers, as well as their difficulty fitting into the “good old boys club” or getting promoted. Tellingly, the report says “most of the participants would not encourage other women in their lives to join the department.” Councilmember Moore was the only person who alluded to this issue.

In the last few months, two female officers have filed discrimination lawsuits against SPD, another data point omitted from the discussion.

A question of morale

Front and center at many of these meetings has been the discussion about officer morale, with Senior Deputy Mayor Tim Burgess saying, “Police officers are very sensitive to what elected officials are saying and doing” and giving the new City Council credit for changing the atmosphere for officers.

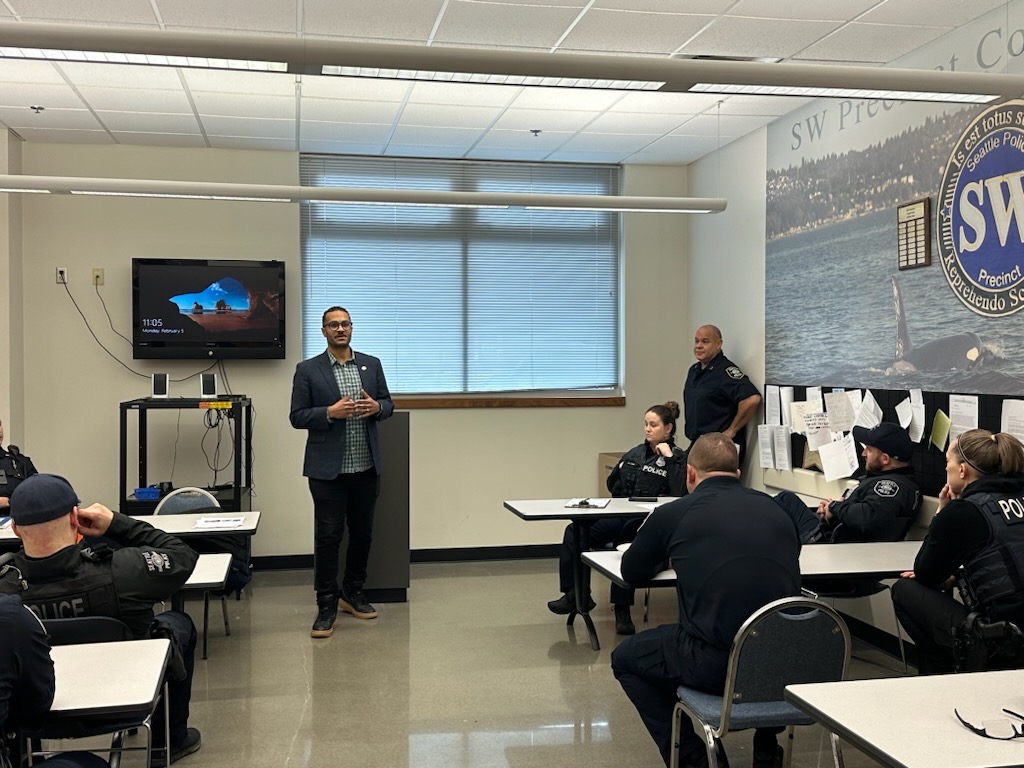

In addition to conversations about many potential officer incentives and higher pay, councilmembers are attending roll calls and sharing their vocal appreciation for Seattle’s police officers, with Councilmember Rob Saka going as far as to ask constituents to fill out a “thank an employee” form on SPD’s website in his weekly newsletter.

While low officer morale is most commonly blamed on the defund pledge most councilmembers made in 2020 in the wake of nightly illustrations of police brutality by SPD, Chief Diaz has another theory that interactions with the Office of Police Accountability (OPA) are causing his officers’ low morale. At Tuesday’s meeting, he said, “One of the things that becomes sometimes a morale issue is… that we have such a huge robust level of accountability that it becomes as soon as they see an OPA confidential it’s like… even though they feel like they haven’t done anything wrong, it becomes an emotional drain on them.”

In other words, Chief Diaz believes Seattle’s robust accountability system, which has never been implemented as designed because of the latest SPOG contract that hasn’t allowed the 2017 accountability ordinance to go into full effect, decreases officer morale. He would like lower level complaints to go back through sergeants instead of through the Office of Police Accountability (OPA), and he would like to streamline use of force reports to prioritize getting officers back out on the streets more quickly.

Councilmember Kettle also referenced the King County Jail as a morale issue, presumably referring to the jail’s current booking restrictions.

Not raised in these discussions is the possibility that SPD’s low morale might be in large part caused by the department’s actions in 2020, which led to a widespread lack of community trust in the department that has not been adequately addressed.

‘Rising to the Moment’

Mayor Harrell spoke to some of these issues at a public safety forum held last week, the first of several. The rest are planned to be precinct-based in April.

“I hope we’ve impressed upon you our ability to rise to the moment in our commitment to you,” Mayor Harrell said at the end of the forum, calling out the pre-K upstream investment he said was suggested by Burgess many years ago. “We’ll continue to go as upstream as possible, we’ll continue to arrest when we have to make arrests, we’ll continue to treat people who are unhealthy and sick, and we’re going to do it with you.”

During the forum Harrell suggested a ballot initiative that would allow the city to regulate firearms and establish its own gun control laws. He also said the city is making progress hiring police officers.

He spoke in favor of acoustic gunshot location systems, saying he wants accurate data of where guns are being fired in the city. His only rebuttal to critiques of this surveillance technology was to insist Black and brown neighborhoods wouldn’t be surveilled as long as he is Mayor, even though his administration is trying to push through three different surveillance technologies that have documented negative impacts on communities of color and it is physically impossible for him to be Mayor forever.

Later in the forum, he said, “I’m telling you, 10,15 years from now, you heard it first…you’re going to see the use of technology that’s all around the city… you’re going to see it in the neighborhoods.” He added, “People don’t trust the government, they certainly don’t trust surveillance tools. Hell, I don’t.”

And yet he envisions a future in which our city is blanketed with the very surveillance tools he claims not to trust.

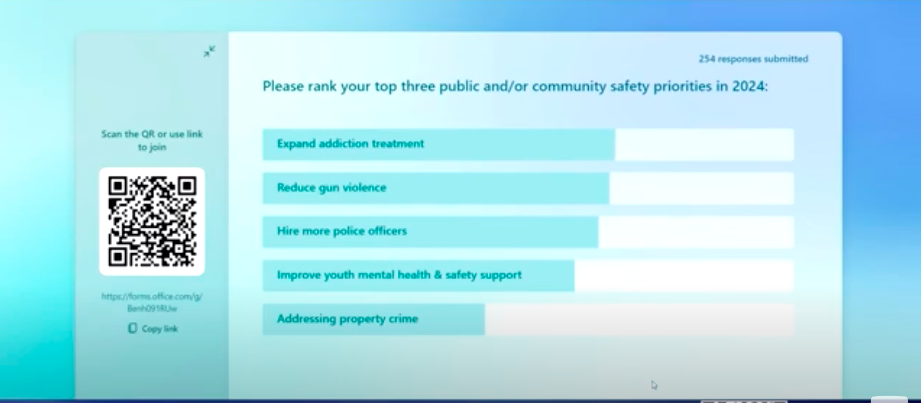

While the public safety forum on Thursday was not publicly promoted until two days prior, the city sent out invitations to certain chosen people and at least one group the weekend before, which might have affected who was able to reserve a spot in the limited library space. Even so, the last polling question of the night, which asked participants to rank their top three public safety priorities in 2024 ended with “Expand addiction treatment” in the top slot, followed by “Reduce gun violence.” The priority “Hire more police officers,” which has been getting so much emphasis, vacillated between the third and fourth spots along with “Improve youth mental health and safety support.”

When even a “friendly” audience doesn’t share elected officials’ top priority for public safety, it is only common sense to wonder why more importance isn’t being placed on other problems, whether that be investing in programs that actually prevent gun violence, addressing the fentanyl crisis, or suggesting innovative solutions to the affordable housing crisis and looming budget deficit.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.