The Seattle Planning Commission late last week joined the chorus of voices raising significant questions about Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed One Seattle Comprehensive Plan housing and job growth strategy. The plan has already drawn criticism from housing advocates, state legislators, and the chair of the city council’s land use committee, but the opinions from the planning commission, the official body specifically tasked with providing recommendations around how the city plans for growth, could carry a special significance.

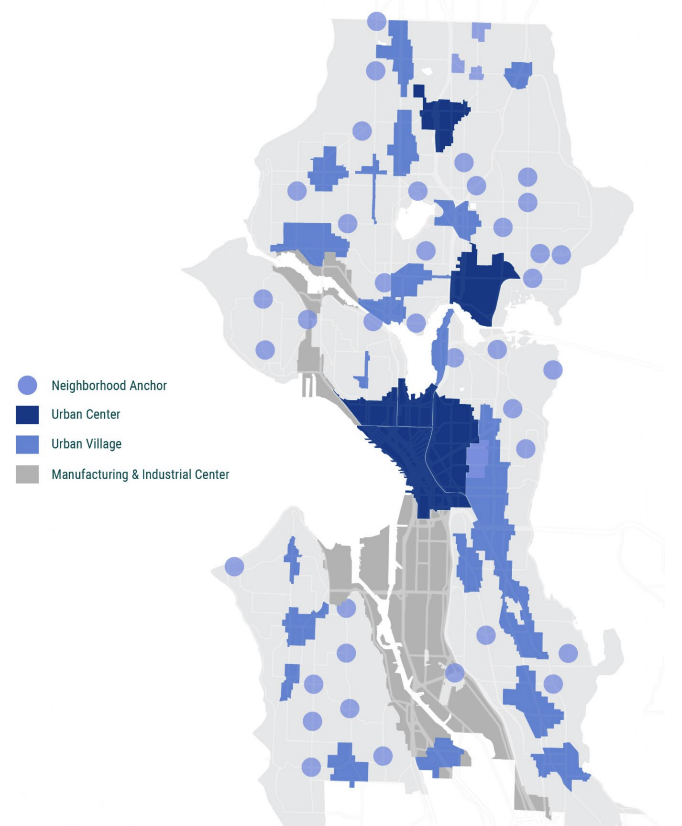

At the first of what will become numerous meetings picking apart the One Seattle plan last Thursday, there was fairly broad agreement from commissioners that as proposed, it falls well short of what will be needed to achieve the goals they laid out in 2022 in advance of work starting in earnest on the proposal. Those goals included steps to make Seattle a full 15-minute city, expansion of the existing urban village system into a “network of complete and connected neighborhoods,” and more robust strategies that actively address displacement of people and business from the city.

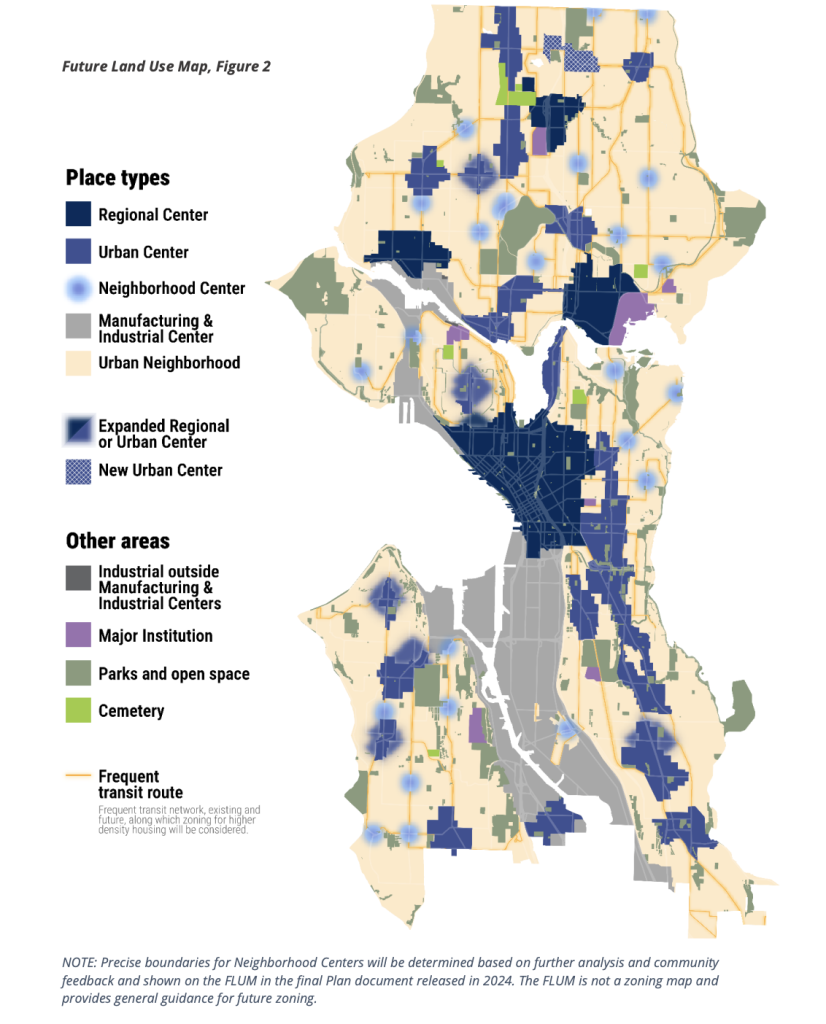

The Harrell administration’s plan largely doubles down on the way the city has grown over the past few decades. It renames, and in some cases slightly expands the existing “urban villages” where the majority of new homes have been built over that time, now calling them urban centers. And targeted upzones would be focused on 24 new “neighborhood centers” where there are existing neighborhood business districts, like in Georgetown, Maple Leaf, or Montlake, but those upzones are not planned to extend more than a block or two in any direction.

The lion’s share of development would continue to happen on a small minority of the land area, despite the proximity of existing low-density neighborhoods to regional job centers like downtown or the University of Washington. Only one new urban center is proposed, around the NE 130th Street light rail station opening in 2026, but one isn’t proposed on Seattle’s side of the city border near Shoreline’s NE 148th Street station.

Proposal is “propagating the status quo”

“This heavily weighted on the centers [plan] just continues to uphold and perpetuate the same patterns of exclusion that we’ve seen for decades, if not over a century in Seattle,” said McCaela Daffern, one of the commission’s co-chairs. “While the plan does acknowledge and say that [it] is approaching its land use patterns in a way that will repair harms from past racially exclusive and discriminatory housing and land use practices, I question whether or not this response is actually meaningfully addressing that because it truly is sort of upholding the same patterns of exclusion that we’ve seen.”

“These zones may change in the future, but currently, it’s kind of propagating the status quo here,” Commissioner Matt Hutchins (who is also an occasional contributor with The Urbanist) said.

Since they released their proposal earlier this month, Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) and Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office have been defending it by pointing to the city’s robust growth rate under current zoning restrictions. The proposal they put forward officially targets 100,000 new homes over the next 20 years, but the administration claims more housing growth is possible citing an estimated buildable capacity for 160,000 homes that it says exists now under existing zoning without any changes.

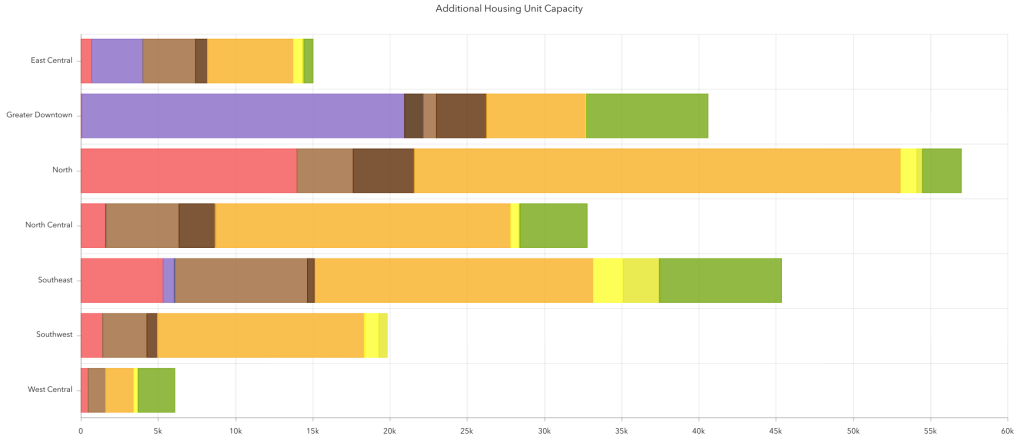

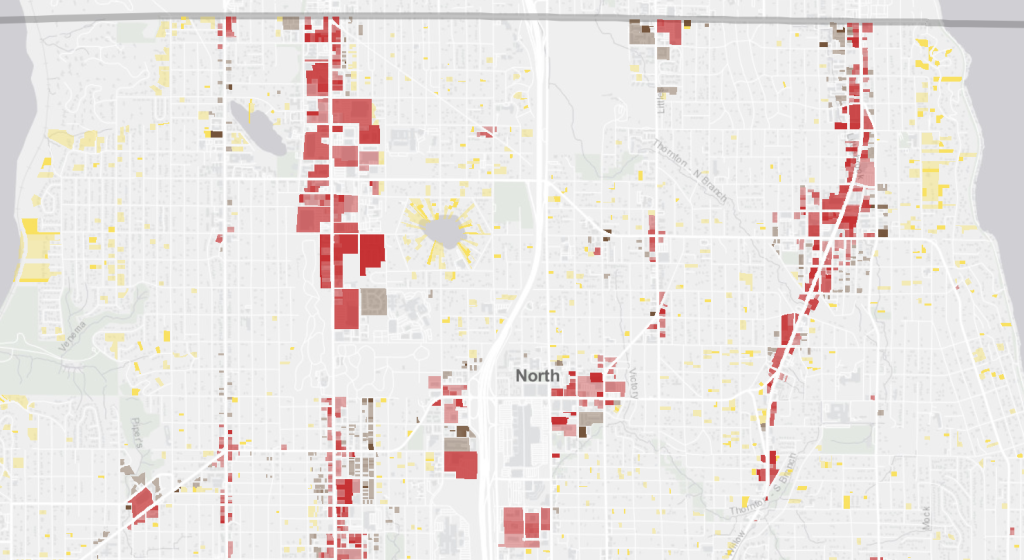

The capacity for those new homes is largely focused in urban centers and villages. Only 3% of that capacity exists in Queen Anne and Magnolia, 8% in Central Seattle outside of the Capitol Hill, with close to one in four (23%) of those potential units located north of 85th Street, and 19% in Southeast Seattle. Most of that development capacity in place today is along busy, dangerous arterial streets like Aurora Avenue, Lake City Way, and Rainier Avenue.

The planning commission wants more details on how the Harrell Administration tossed plans for an additional 19 neighborhood centers after studying a total of 43 in its initial scoping work for the plan in 2022.

“We find that the criteria for neighborhood centers is not clearly articulated, and that more locations should be designated as such,” Commissioner Rick Mohler said. “It’s already been discussed that we’re not providing for enough additional housing to meet future demand. […] In addition, we are not planning for the existing unmet housing needs with our current growth target, and this should be included as well.”

The neighborhood centers that were dropped from the One Seattle plan include one near Seward Park, Mayor Harrell’s neighborhood, along with areas like Alki, Magnolia, and North Capitol Hill.

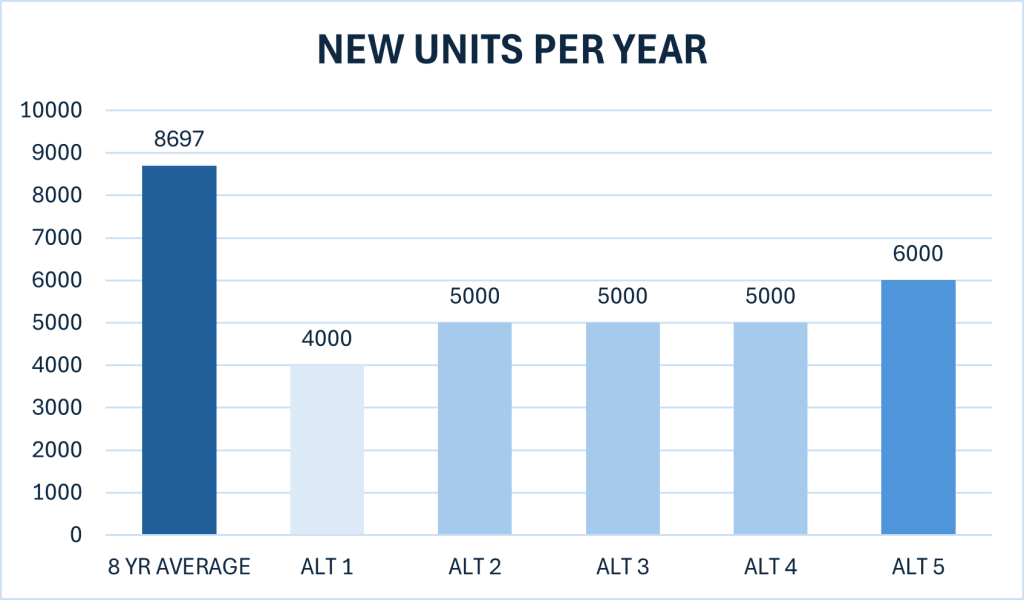

In noting how unambitious any of the proposed growth alternatives that the Harrell administration chose to study were, including the most aggressive one (Alternative 5), which the current One Seattle plan fall short of still, the commission noted that Seattle has produced on average nearly 8,700 new homes over the past 8 years. Yet even Alternative 5 targets just 6,000 homes per year over the full life of the plan.

Restrictions on redeveloping formerly single-family lots

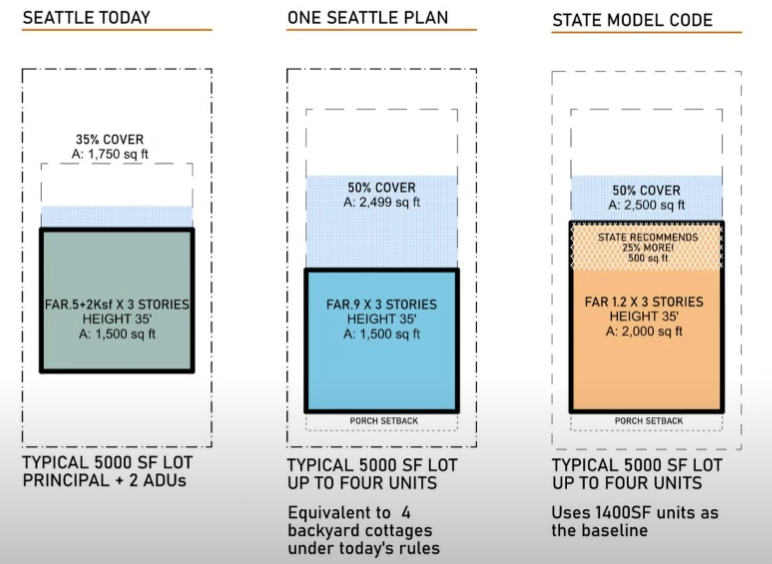

The one element of the plan that the commission noticed on their first initial review was building restrictions on how much of a lot developers would be able to utilize if wanting to develop four units, the new minimum standard in Washington’s large cities thanks to House Bill 1110 passed in 2023. The commissioners noted that even though the number of homes per lot is allowed to increase, the City still wants to heavily restrict the floor area ratio (FAR), which caps the total building space allowed. This forces smaller homes.

“Under the One Seattle plan, that hasn’t changed: we’re essentially still at a 0.9 [FAR], same height [limit]. We changed setbacks a little bit, but we’ve just kind of cut the pie into four slices instead of three,” Hutchins said. “So you can see that what we’re expecting in most of the urban neighborhoods is that they’re the exact same size building as what we can produce today.”

Hutchins pointed out that the state’s newly developed model code ordinance, which would take effect in any city that doesn’t adopt its own regulations to comply with HB 1110 by next summer, would allow much bigger homes than what the Harrell administration is proposing. This is likely going to have a big impact on how much “missing middle” the city actually sees developed, if it’s adopted.

These proposed requirements are drawing the attention of state lawmakers, including Rep. Jessica Bateman (D-22, Olympia), the architect of HB 1110, who has suggested it’s not clear whether Seattle would actually be complying with state law by moving forward with this.

Ultimately, the commission questioned whether the city’s goals and proposed policies are actually carried into the way that the plan would actually be implemented. “The city’s done on a great job of acknowledging at a high level, summarizing in their [housing] element, past harms and racial discrimination,” Daffern said. “And yet, we’re not sure if the plan does follow through to identify adequate strategies to repair those harms.”

While a full backpedal from the Harrell administration isn’t likely, it will fall on groups like the Seattle Planning Commission to work with the Seattle City Council to amend the plan and bring it more in line with their vision over the coming months. Given the significant shortcomings they identified, they have their work cut out for them.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.