Mayor Harrell and the new city council are contemplating budget cuts and raiding JumpStart payroll tax revenue to address a $230 million budget deficit.

With six new members and a significantly more centrist majority than in previous years, the Seattle City Council will have to confront a projected $230 million deficit when it grapples with drafting a biennial budget this fall.

How to address the city’s deepening housing crisis will bump up against the new council majority’s stated goal (echoed by Mayor Bruce Harrell) of finding ways to cut the city’s $1.7 billion general fund budget rather than raising taxes.

During a budget briefing in the council’s finance committee in late February, it became clear that one tempting revenue source will be the nearly $300 million generated each year by the JumpStart payroll tax on high-earning employees at large companies. By law, those funds are designated specifically for affordable housing, economic revitalization, equity-promoting programs, and efforts to address climate change. The council could, as it has in the past, pass legislation removing those restrictions and shifting some revenue to the general fund. But advocates for affordable housing worry this would set back critical programs funded since the tax went into effect in 2021.

“It will be totally traumatic and horrible if the portion of JumpStart that goes to affordable housing gets cut,” said Sharon Lee, executive director of the Low Income Housing Institute. “Because we have a humanitarian crisis we’re facing — around rent increases, people not being able to live in their own neighborhoods, historic residents who are getting gentrified out.”

Even so, the incoming majority — led vocally by Council President Sara Nelson — will likely tap into JumpStart to balance the city’s books. Nelson declined to be interviewed by The Urbanist for this article, but in an op-ed for the Seattle Times in January, she took swipes at JumpStart and vowed to “break our reliance on new revenue (taxes) to pay our bills.”

“The council raised over a billion dollars in new taxes in the last three years to fuel spending on new programs,” Nelson wrote. “Instead of ‘jump-starting’ Seattle’s recovery, hundreds of businesses closed or left downtown, taking those jobs elsewhere.”

Mayor Harrell is also on board with cuts rather than new revenue to fix the city’s deficit, noting in his state of the city speech in February that “passing a new or expanded tax will not address the fundamental issues needed to close this gap.” In January, Harrell instituted a hiring freeze across most City departments, exempting police and fire.

Jamie Housen, a spokesman for the mayor’s office, said, “To address the projected deficit, we’re reviewing base budgets across all departments to understand what’s working and what’s not, as well as what level of service we can afford to sustain. We’re also looking into recently created revenue and whether we are maximizing its utility.”

Councilmember Tammy Morales, who was an ardent supporter of the “Tax Amazon” effort and voted for the JumpStart measure in 2020, told The Urbanist, “When we passed JumpStart, we made a promise to our community and a legal commitment to use that funding to create affordable housing, help small businesses, fund the Green New Deal, and spur equitable development. This City of Seattle shouldn’t break that promise by raiding JumpStart.”

Inflation and high interest rates contribute to funding gap

In a presentation to the council’s finance committee in late February, city budget director Julie Dingley laid out how the city got itself into a financial hole — and what will be required to balance its books before the end of the year.

From the Great Recession in 2008 until the pandemic, Dingley noted, the city experienced robust economic growth (and thus, solid tax revenues) as a result of the booming tech industry. When Covid hit in 2020, and tax revenues plummeted, Seattle bucked national trends and chose instead to boost services and increase spending, thanks primarily to JumpStart and an influx of federal relief funds. “We were able to more or less defy fiscal gravity from the time of that recession until today,” Dingley said. “It bought us a lot of time to exist at this higher service level, this higher staffing level.”

Those federal relief dollars are all spent, and now a combination of declining tax revenues, high interest rates, and inflation are contributing to a deficit that will climb to $230 million in 2025 and $452 million in 2026 if left unaddressed, Dingley said.

The discretionary part of the city’s $7.9 total billion budget is currently at $1.7 billion and is expected to climb well beyond $2 billion in the next two years. Dingley noted that inflation is driving up costs — and that labor represents the biggest surge in spending.

On March 6, the mayor’s office announced it had reached a tentative agreement with 16 unions representing about 7,000 city employees (the contract must be approved by the city council before becoming valid). The four-year contract, effective retroactively to 2023, raises wages 9.7% by the end of 2024 and at a level between 2% and 4% annually based on the local consumer price index. A long-delayed contract with the Seattle Police Officers Guild is expected this year.

The biggest slice of the general fund spending pie goes to public safety (at $796 million in the adopted 2024 budget it accounts for 46% of all general fund spending). This includes police, fire, the Office of Emergency Management, and Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE), the mayor’s new department tasked with non-police responses to mental health and other non-violent crises.

Those hoping the mayor or city council will look for budget savings in the realm of public safety will likely be disappointed — Councilmember Nelson has indicated on many occasions she believes Seattle Police Department officers should get substantial pay raises. New Councilmember Bob Kettle, who chairs the public safety committee, has asked police officers thinking of quitting or retiring to consider staying one more year, hinting they’ll be rewarded with a better contract by the new council.

In her presentation, Dingley noted that many sources of revenue for the city have remained flat or have not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Though housing prices have consistently climbed, property taxes (which account for 24% of general fund revenue) have lagged behind the rate of inflation because state law caps their increase at 1%. Though the local consumer price index rose by 19.5% between 2021 and 2024, city property tax revenue only increased by 8.9% in the same period.

“That’s a huge chunk of the revenue that is not going to keep up when you’re talking about the high inflation level,” Dingley said.

Dingley also noted that revenue from the city’s real estate excise tax (REET), which covers residential and commercial property transactions, has dropped precipitously ever since the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to combat inflation. REET tax revenues, which support the city’s maintenance and capital costs, dropped 55% in 2023 from the previous year, a decline not seen since the Great Recession of 2008, when it fell 58%.

“The overall health of REET is a canary in the coal mine for the rest of the city’s revenues,” Dingley said, “because the presence of real estate transactions is an indicator of the health of the economy, consumer confidence . . . and access to capital.” She observed that fewer home sales, in addition to lowering REET revenue, can have a cascading effect on construction and thus impact sales tax and business and occupation tax (B&O) revenue as well.

The $230 million projected deficit accounts for about 15% of the entire general fund, Dingley said — making the problem on a scale Seattle hasn’t encountered in decades. During past budget crunches, the city has asked each department for, say, 3% proposed reductions to their budgets. The mayor’s office believes this approach won’t be sufficient.

“For the first time, we’re asking departments to build their budgets from the ground up,” Dingley said. “This isn’t quite zero-based budgeting — we don’t have the technology in place to be able to support that — but this is as close as we can get with our current tools.”

Will the council jump at the chance to raid JumpStart?

First enacted in 2021, the JumpStart tax (officially known as the “payroll expense tax” or PET), applies only to companies with payrolls over $8.5 million and is applied to salaries higher than $182,000. The tax rate (which is paid by the employer) ranges from around .75% to 2.5%.

Dingley, in her presentation, noted that this payroll tax is a particularly volatile source — she said that 75% of JumpStart’s revenue comes from just 10 high-paying large employers. “So if any one of those big players were to make different choices, that would have huge impacts to the revenue,” she said.

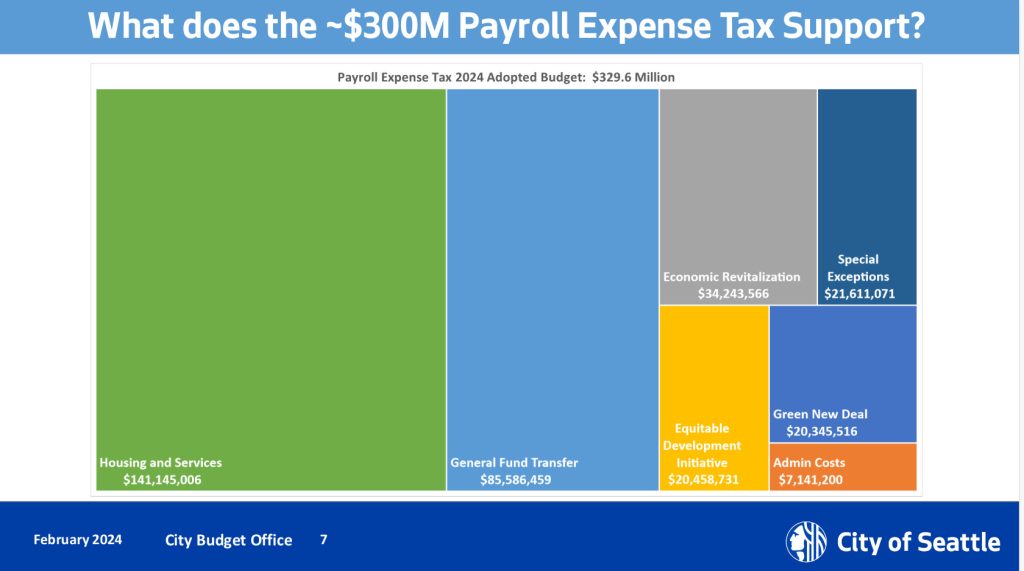

Revenues from the program — originally sponsored by Teresa Mosqueda, who left city council this year after being elected to the King County Council — have generally outpaced projections. In 2021, JumpStart brought in $214 million and this year is expected to net about $330 million. In its first year, all of the revenue was diverted to the general fund to cope with the ongoing Covid-19 crisis.

In subsequent years, portions of JumpStart have been diverted from the program’s four core areas to the broader budget. In the adopted 2024 budget, about $85 million was transferred to the general fund.

Of the remainder, $141 million was allocated to affordable housing and services, $34 million to economic revitalization projects, $20 million to equitable development (including support for South End organizations such as the African Women Business Alliance and the Duwamish Longhouse), $21 million to hire mental health counselors in Seattle Public Schools, and $20 million toward climate change projects such as decarbonizing libraries and helping low income households convert from oil to electric heat.

According to Nona Raybern, communications manager for the Office of Housing, JumpStart accounts for about 40% of the Office of Housing’s current budget, with a total contribution of $383 million from 2021 through 2024. According to Raybern, through 2022, the Office of Housing used $141 million in JumpStart funds for the “acquisition, preservation, and production of over 2,000 rental homes.”

In addition, Raybern said that “Through the lifetime of PET [Payroll Excise Tax], we also created 110 homeownership opportunities with $12 million in PET funding and invested $69 million into operating, maintenance, and services for our permanent supportive housing providers.”

Morales said that JumpStart accounts for nearly 70% of the Office of Economic Development’s funding.

Sharon Lee says that the payroll tax has allowed Seattle’s Office of Housing to leverage more state and federal grants. “If you don’t have local funds matching funds,” she said, “then you can’t compete, and the federal and state funds would go to other other jurisdictions.”

Lee points to the Dockside Apartments project near Green Lake as an example of JumpStart funds being put to their intended use. The 93-unit complex, which, with funds from the city’s Rapid Acquisition Program, Low Income Housing Institute was able to purchase an existing building and convert it to 70 units of permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless people and 22 units for restaurant or service industry workers making minimum wage.

“In order to buy the building, we had to leverage state funds,” Lee said. “If we didn’t have the local sources, we couldn’t get the state to match.”

If raising other taxes or fees is off the table, and revenues from existing sources remain flat (a more detailed estimate of predicted revenue is expected from the city budget office in April) then there aren’t many options other than cuts and raiding the payroll tax.

Councilmember Dan Strauss, who chairs the finance committee and who did not respond to requests for an interview from The Urbanist, said during February’s budget briefing that he’s open to finding efficiencies throughout city government. “We could have made some of these choices during the pandemic under duress,” he said. “We have a better opportunity with a longer runway today to make these long term structural changes to our budgeting. This is an opportunity to have a comprehensive review and examination both from the top down and the bottom up — which is in contrast to most years where it’s been incremental change.”

Morales, though, said she favors looking for new sources of revenue rather than cuts, which she calls “austerity — balancing the budget on the backs of working-class people by cutting funding for things like affordable housing, homelessness services, and other essential programs.”

Acknowledging she’s now in the minority, however, Morales concedes she’d be open to shifting some revenue from JumpStart. “I would be willing to continue the past practice of allowing the first $80 million to go to our General Fund. Also, if the intent of the executive is to use the payroll expense tax to fix our structural budget issue, that presumes the tax is permanent.”

The Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, which enthusiastically backed many of the centrist candidates now in the council majority and opposed and legally challenged JumpStart, urged the council to consider cuts before raising any new revenue. Spokesperson Lars Erickson said in an email that the council should eliminate or reduce spending on programs that aren’t achieving desired outcomes.

The Chamber also asks for a hard look at JumpStart. “The city should review all General Fund revenue — including restricted revenue — against all spending, and against city and community priorities, every budget cycle,” Erickson said. “Simply earmarking taxes is not a measure of success — making progress on things like housing and public safety is.”

Lee says she’s open to a rigorous review of city budgets, but is firm that funds for services and housing need to take priority. “There are cost effective solutions that can shelter people humanely,” she said. “That could be more non-congregate shelters. It could be purchasing some hotels. It could be expanding more tiny house villages. These are all options to save lives. It’s possible. I mean, we’re a wealthy community.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.