Even after redesigning plans for a brand new Alki Elementary School to accommodate an additional 15 off-street parking spaces that weren’t originally in the plans, Seattle Public Schools (SPS) finds itself mired in another appeal over the project. The school district’s problems getting the project approved are exacerbated by Seattle’s arbitrary minimum parking requirements, which still require every new or modified public school to include a certain number of off-street parking stalls based not on classroom space but on the size of an auditorium or public assembly room, a requirement that doesn’t reflect current best practices around school construction.

The appeal, filed late last week by a group calling itself “Friends for a Safe Alki Community,” seeks to reverse the City of Seattle’s latest approval of a departure letting the district move ahead, but the text makes it clear that the appellants main concern is with the overall plan for a larger Alki Elementary that would increase enrollment capacity to accommodate the city’s future growth. The appeal is led by nearby resident and retired lawyer, Steve Cuddy, who claims around 50 members in his group. It was not Cuddy who originally appealed the project’s approval last year, but both appeals have targeted the proposed deviation from required parking minimums.

“The Seattle Public Schools is seeking approval for deviations from code requirements […] to nearly double the number of children and staff at Alki Elementary school — despite declining enrollment — while removing much needed parking on a site already plagued with parking, traffic, and safety issues due to the logistical realities of the small site served by only one narrow street,” the appeal filed last week states. “A large school at this location is simply not feasible without significant impacts which cannot be mitigated due to unchangeable site constraints.”

Last year, Seattle’s deputy Hearing Examiner, Susan Drummond, sided with the initial appeal of the project, leading to SPS to add back the 15 stalls, but that was not enough, according to the residents filing this latest appeal. A request from the district to take the issue to King County Superior Court last year was denied.

Delays to the project have already cost the district an additional $3 million in direct construction costs, not including legal fees or the costs to create new architectural plans. And the opening of the school, already postponed from fall of 2025 to fall of 2026, could be pushed back even further. “I would just say that the meter’s running, unfortunately, the longer it takes,” Vincent Gonzales, a senior project manager with SPS, told Seattle’s school traffic safety committee in February, when the appeal was expected but not yet filed.

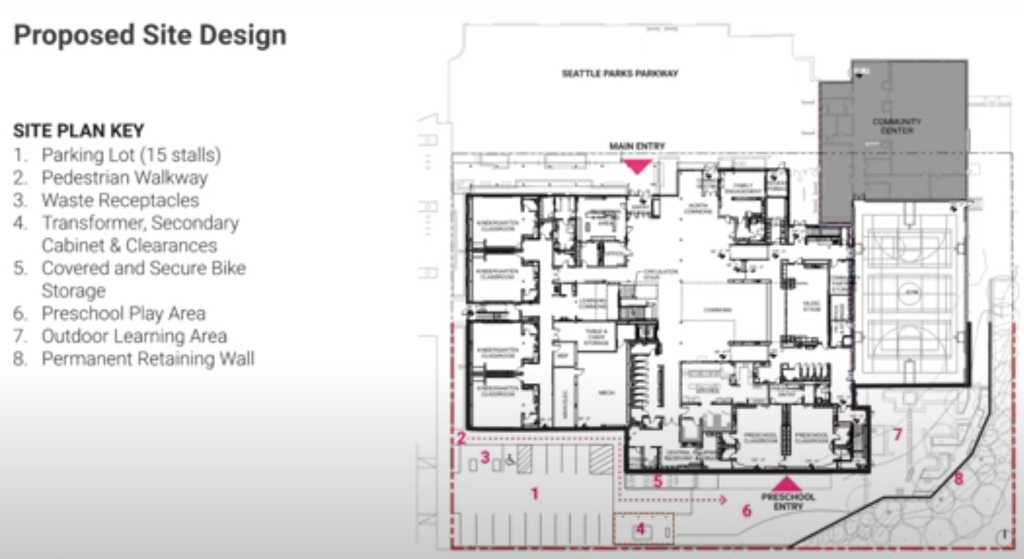

Last fall, it looked like Seattle Public Schools may have to redesign the site plan to remove classroom or outdoor learning space, a fact that Seattle’s Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) considered when approving the variance. “Due to the limited nature of this site, providing on-site vehicular parking would result in sacrificing educational program and outdoor learning opportunities,” that approval from last May noted. Instead, the district was able to squeeze in space for 15 stalls by removing a planned loading dock at the school, relocating utilities (which adds costs), and eliminating a dedicated pathway for preschoolers and their families to access the site.

The loss of the loading dock is likely to be the most impactful change stemming from the new lot, potentially trading health and well-being considerations for SPS staff to assuage neighborhood concerns. “We used to have a loading platform so that the custodians would have a little bit of an elevated stage from which to just dump their garbage,” Becky Hutchinson of Mahlum Architecture, the firm working on the project, said in February. “It was shared to us that that is the greatest source of [Labor and Industry] complaints, which is having to haul the dumpsters — the garbage — overhead. And so we had a platform for them, but that’s gone now.”

To meet code requirements without a departure, an additional 33 stalls, or over twice the amount that the district has already accommodated, would need to be provided on the small 1.4-acre site which has been home to a school since 1913. “The additional studies that the design team did show that you cannot get more than 15 stalls without taking away, for example, the preschool classroom on the first floor and eliminating this whole program from the school site,” Hutchinson said.

When Hearing Examiner Susan Drummond ruled in favor of the appellants last year, directing the district to address how it was accommodating parking, Drummond mentioned that SPS could potentially acquire nearby properties to create new off-street lots, an absurd proposition on its face. But the district did try and consider additional ways parking could be accommodated nearby. “We looked at also if there were any parking lots, churches or anything that we partner with to actually do like a shared parking [situation] but there aren’t any,” Brian Fabella, Alki Elementary’s project manager, said last month.

SDCI is currently engaged in work that would change Seattle’s code requirements to actually meet the standards for new school construction, eliminating the costly and burdensome process that SPS currently goes through to get departures approved for every project, but so far there are no signs that work is wrapping up and heading to the Seattle City Council anytime soon. Elsewhere in the city, SPS has been able to move forward with new school buildings without any off-street parking, including at a new Montlake Elementary, but the process to receive departures adds costs to every single project that the district pursues — costs that all Seattleites ultimately shoulder through higher taxes.

Even if Seattle’s Hearing Examiner ends up deciding that the 15-stall plan is sufficient, the project will likely be delayed another six months. It should be a wake-up call to take a look at Seattle’s land use code and how it treats these essential facilities, but it’s not clear whether anyone will actually heed that call.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.