The state is poised to allow more enforcement of bus lanes via camera, and drop strict requirements on who can review camera footage.

In an attempt to improve roadway safety and transit mobility, the Washington State Legislature has approved fairly sweeping changes to existing state law permitting the use of automatic cameras as traffic enforcement tool. The framework leaves the ultimate decision to implement cameras up to local jurisdictions, but the changes represent a clear attempt to make traffic cameras easier and more attractive for cities and counties to implement.

House Bill 2384, sponsored by Representative Brandy Donaghy (D-44, Snohomish), builds on reforms passed as part of the 2022 Move Ahead Washington transportation package that dramatically expanded where cities were allowed to use automatic cameras to enforce traffic laws. And it tweaks some of the financial incentives that may prompt cities to decide to use cameras — and the incentives that might prompt cities to keep cameras in place as opposed to investing in infrastructure that stops the underlying behavior. The bill awaits signature of Governor Jay Inslee, whose office testified in support of the measure.

2022’s legislation gave the go-ahead for cities to put automatic speed cameras in places where they couldn’t before: outside hospitals, parks, along routes where kids walk to and from school, and at intersections that have a higher-than-average history of crashes. Prior to that, they were only allowed to enforce red light running and within school zones. HB 2384 keeps the new authorization in place, but removes a requirement that 50% of the net revenue from those new camera types is required to be handed back to the state, to be deposited in the Cooper Jones active transportation safety account.

The dollars generated by drivers who violate traffic laws will instead stay at the local level, where they are required to be spent on physical infrastructure that improves safety. However, if a city has a camera in a specific place for more than three years, 25% of the fines generated after paying for administration will have to be remitted to the Cooper Jones account, creating an incentive for cities to not let their cameras remain in spots where they generate a lot of tickets but rather continue to evaluate where cameras can have the most benefit.

HB 2384 also adds a cap to the total amount an automatic camera ticket can be for an individual citation: $145, with the amount allowed to double to $290 for speeding in a school zone. These amounts are roughly in line with ticket amounts in Washington’s major cities: Seattle’s red light camera tickets cost drivers $139, and school zone camera infractions are $237.

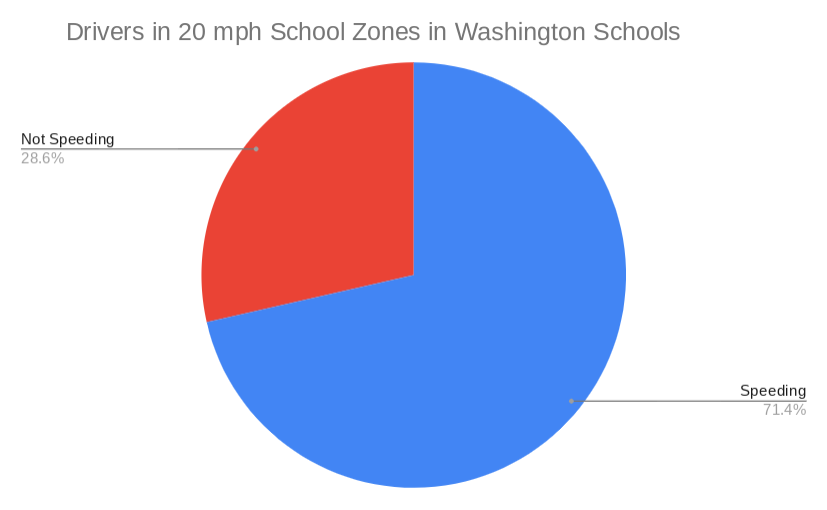

With speeding cited by the Washington Traffic Safety Commission as one of the “fatal four” behaviors most seen in traffic crashes, lawmakers hope deployment of cameras can reduce the rate of drivers exceeding the speed limit in the face of excessive speeds seen across the board statewide. A survey the commission completed of nearly 20,000 drivers outside active school zones found that over 70% of drivers were speeding, but the lowest rates of active speeding were observed at schools with automated camera enforcement.

“Addressing excessive speed, especially in zones where we have vulnerable users, or school zones, or park zones, or hospital zones is critically important,” Senator Marko Liias (D-21, Edmonds), chair of the Senate’s transportation committee, said ahead of the bill’s final vote in that chamber. “Research shows that the use of automated cameras works. In our jurisdictions here in Washington, the repeat infraction rate is less than 10%. Most people get a ticket once and they never speed in that zone again and the folks who walk to that school or that park or that hospital are safer for it.”

More public employees can review traffic tickets, but there’s a catch

Perhaps the biggest change HB 2384 will prompt doesn’t involve where cameras can go, but who is allowed to ensure citations actually get issued. Under current state law, only sworn police officers can review footage and sign off on sending a ticket to a specific driver, a framework that creates problems given staffing shortages at police departments across the state. Last year, the City of Seattle lost millions of dollars in revenue that otherwise would have been available, except the Seattle Police Department didn’t have anyone assigned to review those tickets.

Thanks in part due to advocacy from the Seattle School Traffic Safety Committee, the City of Seattle advocated for the state to change the law to allow non-sworn officers to review tickets. Their wish was granted: HB 2384 allows either a civilian employee of a law enforcement agency or a public employee of a city transportation or public works department to review tickets.

“The element of this legislation that’s particularly important to the City of Seattle is the section that gives us the ability to use well-trained public employees that are non-commissioned police officers,” Tim Burgess, Seattle’s deputy mayor for public safety, told the House transportation committee this January. “Like cities around the country, and across the state, we’re having trouble recruiting police officers, and we would rather take those officers who are sitting in a room looking at video all day, and send them out to the street for patrol.”

But advocates for this change have another big hurdle: local police contracts. Even if the change in state law allows civilian review of infraction footage, allowing that may be subject to bargaining with police unions, groups that have traditionally been reluctant to give up tasks that only sworn officers are able to perform. This provision could be a sea change in the long-term, but may not pay dividends for several years due to that bargaining element.

More transit lane camera enforcement allowed in King County and statewide

The only jurisdiction in the state that had been able to issue tickets to drivers violating restrictions on bus lanes was Seattle. A pilot program approved by the legislature allows bus only lanes, along with cameras to enforce crosswalk and intersection blocking, on a fairly restrictive set of streets focused around downtown. Thanks to an amendment introduced by Senator Javier Valdez (D-46, Seattle), those restrictions will stay in place, but the bill also includes new authority that will allow transit agencies to enforce bus-only lanes elsewhere.

In King County only, transit agencies will be able to enforce bus only lanes directly on transit vehicles. King County Metro and Sound Transit should both theoretically be able to take advantage of this authority, though a lot of questions remain about how the agencies would decide which vehicles get cameras and which routes they’d be deployed on. Washington, D.C. has been utilizing onboard cameras to enforce bus lanes since last year, joining the ranks of jurisdictions around the world using the same technology.

Statewide, transit cameras are authorized under HB 2384 only on “bus rapid transit” routes — though no definition of bus rapid transit exists in current state law, a fact that came to light during the debate over a transit-oriented development bill during the 2023 and 2024 sessions. Generally, bus routes with dedicated right-of-way, fewer stops, and off-board payment have been the ones billed as bus rapid transit, but the definition is squishy. Would a Sound Transit express bus operating in Pierce County qualify as bus rapid transit? It remains to be seen.

Cities still in the driver seat

Ultimately, it will still be up to local governments to deploy cameras in the locations where they can be the most effective. That means it will fall on every individual city and county to ensure they’re deploying cameras in an equitable way.

“We’ve done what we can to ensure that this is a fairly equitable bill surrounding traffic cameras, because historically they have been placed in certain locations, and not placed in other locations for various reasons,” Rep. Dongaghy said at the bill’s first hearing. HB 2384 requires that before localities add new cameras, they conduct an equity analysis that includes “the impact of the camera placement on livability, accessibility, economics, education, and environmental health.” That analysis also must show a “demonstrated need” for cameras based on tangible data like current rates of driver speeds.

In Seattle, a debate over the equity impact of cameras this year is likely as the city continues to plan an expansion of the automatic camera program, including a potential doubling of school zone speed cameras.

Another thing that HB 2384 does is make it explicit that local cities are able to add speed cameras to state highways that are also city streets, like Aurora Avenue N in Seattle or Pacific Highway in Everett. State highways through population centers have a fatal crash rate twice the statewide average and a serious injury crash rate three times the state average, and likely represent the spots where the biggest gains could be gained from camera enforcement. But adding cameras to the busiest streets in the state could impact traffic flow, providing a potential source of political conflict.

While other potential measures that the legislature could implement to make traffic safety gains, such as requiring cities to eliminate free right-on-red or regulating larger vehicle sizes, remain elusive, the Democratic caucus seemed to be in agreement that traffic cameras are a tool that needs to be expanded. Their colleagues across the aisle didn’t agree, with HB 2384 passing on sharply party-line votes in both the House and the Senate. Now it will fall on local governments to prove that the expanded authority was not in vain.

HB 2384 takes effect 90 day after the end of the legislative session, in early June.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.