Sound Transit planners continue to forecast a shortage of trains to provide the level of Link service promised to voters in the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) plans. Consequently, the agency won’t be able to provide six-minute frequencies and four-car trains on all lines. On Thursday, agency planners offered an update to board members on the Rider Experience and Operations Committee on some strategies that the agency is contemplating to partially or fully mitigate this problem.

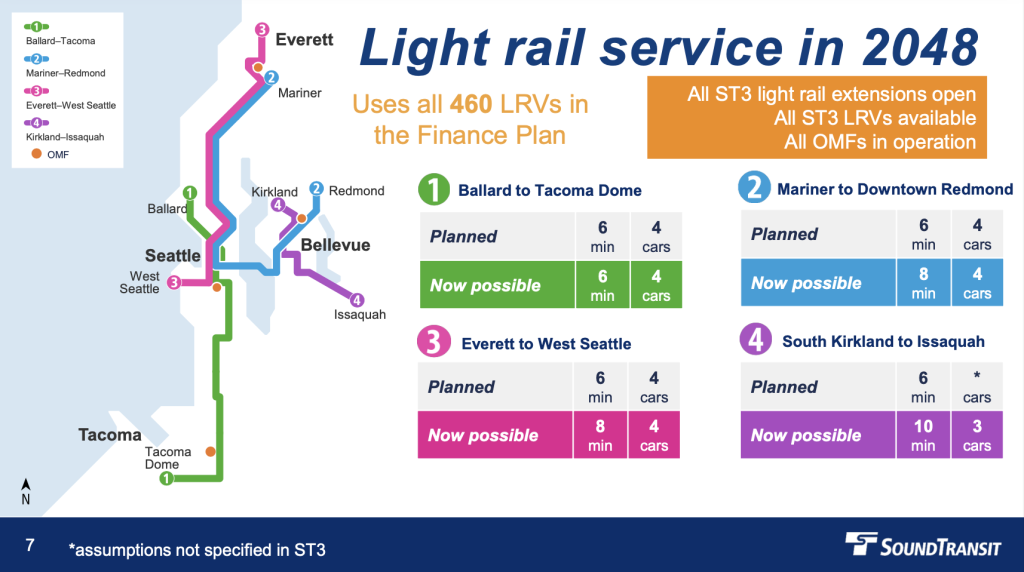

Planners are still projecting a need for an extra 550 light rail vehicles (LRVs) — 90 more than the 460 LRVs budgeted for and assumed in the agency’s financial plan — to provide promised service levels.

Assuming no extra LRVs are delivered, planners believe that only the 1 Line could reach six-minute frequencies with four-car trains. All other lines would see lower peak-hour frequencies (every eight minutes on the 2 and 3 Lines, and every ten minutes on the 4 Line) and the 4 Line would be forced to be limited to three-car trains by 2048 — several years after ST3 light rail expansions are completed and when service levels are expected to settle out.

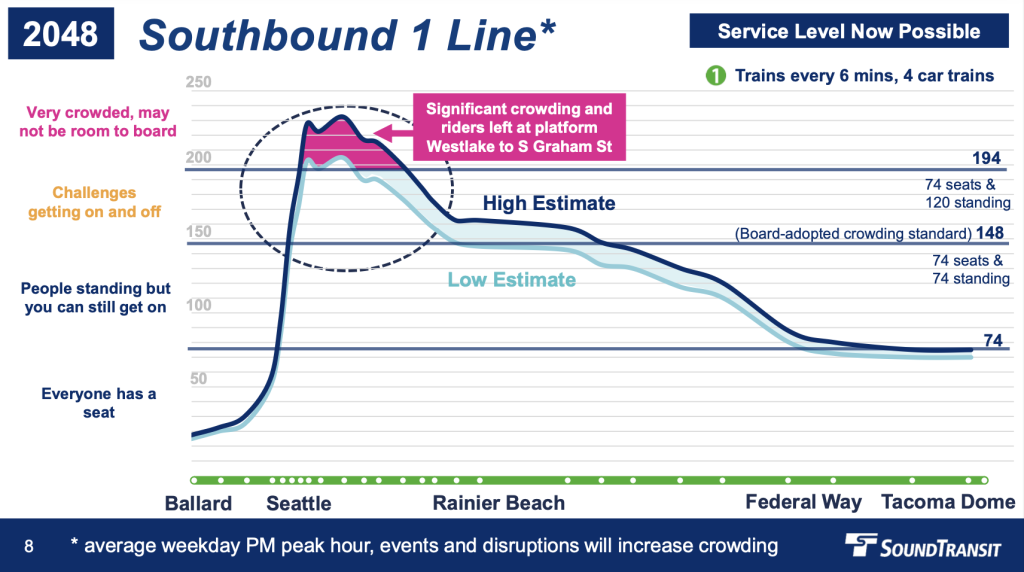

Even with the 1 Line reaching the highest peak frequencies at every six minutes with full-length trains, Sound Transit planners are projecting capacity challenges. Riders throughout Seattle could be left at platforms between Westlake Station and Graham Street Station, and elsewhere in the city getting on and off trains would be a common problem.

After nearly a year of hemming and hawing, Sound Transit planners are finally showing work on how they might mitigate some of the problems. Matt Shelden, an agency planner, outlined two potential approaches and strategies common to both.

In terms of common strategies, Shelden pointed out some ways that the agency could reduce runtimes and fleet spare ratios as well as speed up delivery of LRV purchases and increase LRV onboard capacity. These include the following:

- Reducing run times by adding crossing gates, upgrading singaling systems, enhancing operator training, and studying future grade-separation of at-grade segments. Reduced runtimes for each trip has the benefit of requiring fewer trains to operate service.

- Reducing the fleet spare ratio by expanding overnight maintenance windows, increasing staffing, and completing warranty work on trains (already underway). Reduced spare ratios allows more trains to provide normal service rather than sitting in storage and maintenance facilities.

- Speeding up future delivery of LRVs by increasing order size or options in the Series 3 procurement or starting future procurements earlier, delivering vehicles to match operations and maintenance facility (OMF) availability, and procuring 10 extra Series 2 LRVs (already underway).

- Increasing LRV onboard capacity by removing some seats, restricting bikes and luggage, asking riders to spread out, relaxing crowding standards, and configuring future LRVs for more capacity (already underway).

These strategies are by no means exhaustive of efficiencies Sound Transit could implement to buy back capacity and improve potential service levels, but they would be starting points. (The Urbanist has suggested numerous potential strategies.)

As far as the primary approaches — what Shelden called “bookend approaches” — go, they would be focused on tailoring service to demand and capital investments.

The service-focused approach would restructure service levels based upon peak demand that planners believe will exist in the future. Consequently, service levels would shake out as follows by line:

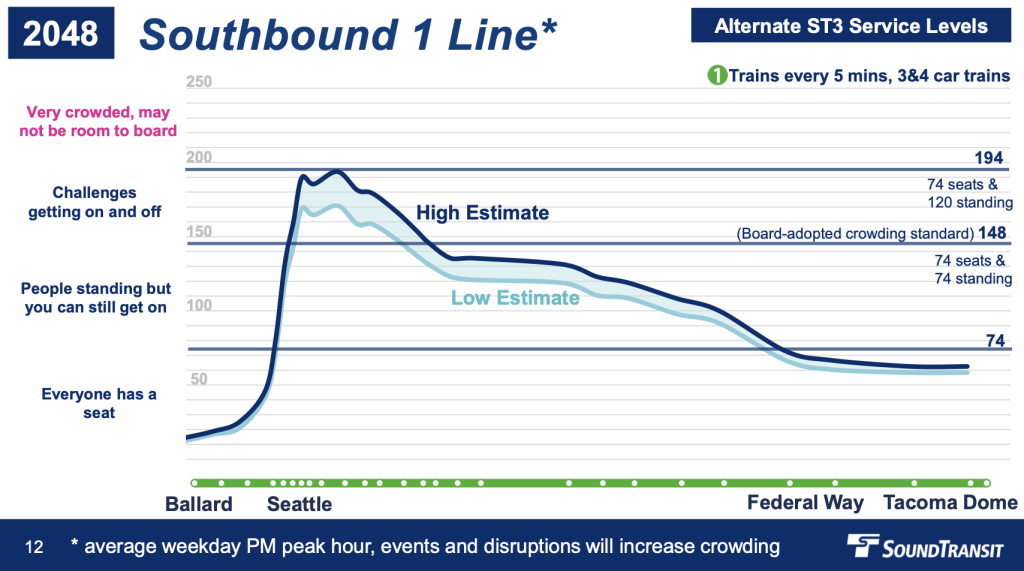

- For the 1 Line, five-minute peak frequencies with four-car trains;

- For the 2 and 3 Lines, eight-minute peak frequencies with four-car trains and allowing for combined four-minute peak frequencies between International District/Chinatown and Mariner stations; and

- For the 4 Line, 16 minute peak frequencies with two-car trains, though if another 12 or so LRVs were purchased (at an assumed cost of $90 million to $110 million), frequency could be improved to every eight minutes.

All of this would require no increase in the fleet (beyond perhaps the 4 Line) and OMFs while addressing most crowding, according to Sheldon.

A slide offered during Thursday’s presentation demonstrated how just bumping up frequency on the 1 Line by one minute could mostly avoid the specter of leaving riders at platforms during peak hours by 2048. Crowding could still be an issue at the busiest stations with riders struggling to get on and off, but riders usually wouldn’t risk having to wait for another train to carry out their journeys.

An another approach outlined by Shelden was a capital-intensive one. It would involve the purchase of 90 more LRVs and expanding OMFs with capacity for another 50 to 60 LRVs. Shelden said that the agency will have some extra storage capacity at planned OMFs, so a full 90 storage spaces wouldn’t be necessary. Nevertheless, this approach is unaffordable in the agency’s financial plan, costing well over $2 billion — and likely considerably more given the agency’s poor cost estimating track record.

Shelden ultimately recommended a hybrid approach of the strategies, stressing flexibility as the system expands. By pursuing the most promising efficiencies and tailoring planned peak service to what the agency is projecting demand to be, service could be better rationalized. Adding in potential capital strategies could further expand capacity and improve service, but that will certainly be a matter of serious debate among the board since it has knock-on effects with added costs and delays to the overall ST3 program. Options for larger vehicle procurements and storage capacity at OMFs could keep that door open though.

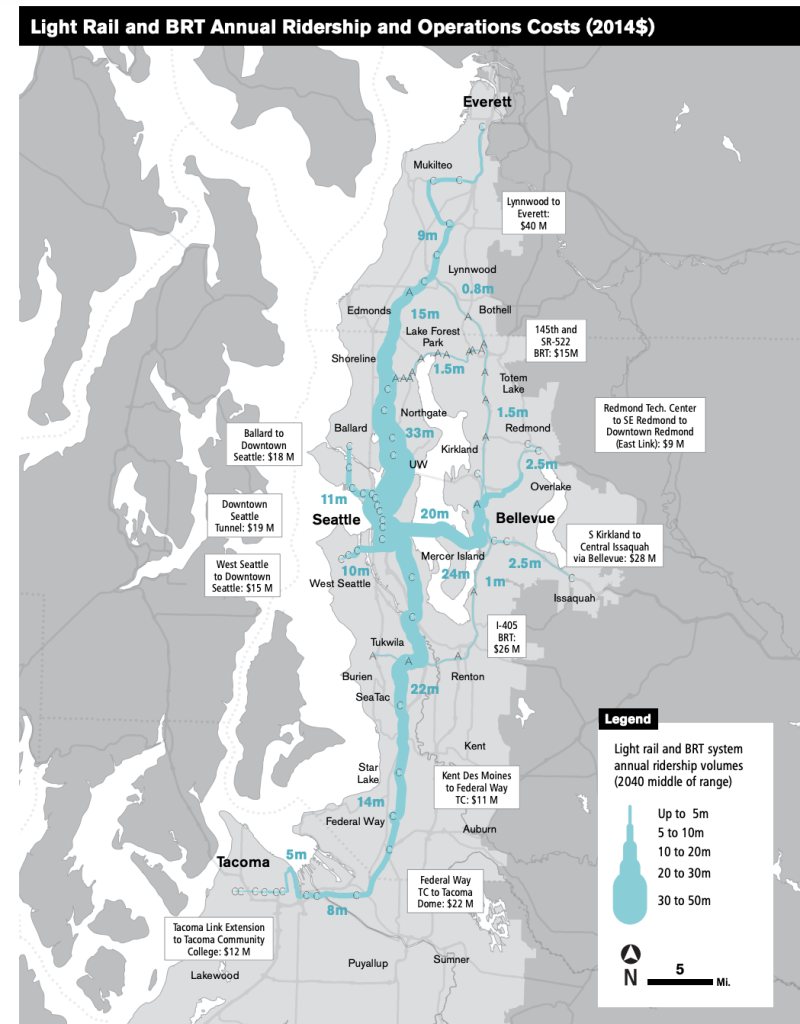

How the agency is forecasting demand is unclear since a specific model hasn’t been shared. But while it’s safe to say that a line like the 4 Line is bound to suffer from poor ridership levels due to freeway-oriented stations, short length, and odd system routings, running service at 16-minute frequencies as agency planners suggested in the Thursday meeting is the kind of frequency that stifles rider demand in the first place. And, if imposed, would almost certainly further crater rider demand.

Also worrying is that agency planners continue to only think in terms of peak-hour service levels. Six-minute or worse frequencies at peak and considerably less off-peak on what’s supposed to be a metro system is a very concerning target. Vancouver, British Columbia runs its SkyTrain network at much higher frequencies throughout the day.

SkyTrain’s Expo Line operates on weekdays every two to three minutes at peak hours, every three minutes at midday, and every every three to five minutes in the evening and at night. Weekend service on the line is about every three minutes, except early in the morning and late at night when it is every four minutes. Only the short branches see lower service. Even the Millennium Line, which has the worst effective service levels, are better across all time periods than what Sound Transit is striving for.

In terms of what Sound Transit planners are proposing, the main drawbacks of their first approach around service is that it still heavily misallocates capacity (number of vehicles) in parts of the system that don’t need full-length trains while generally underserving riders throughout the system with very poor frequencies. This all stems from planners remaining committed to the four-line, spine service strategy, which is the crux of problem.

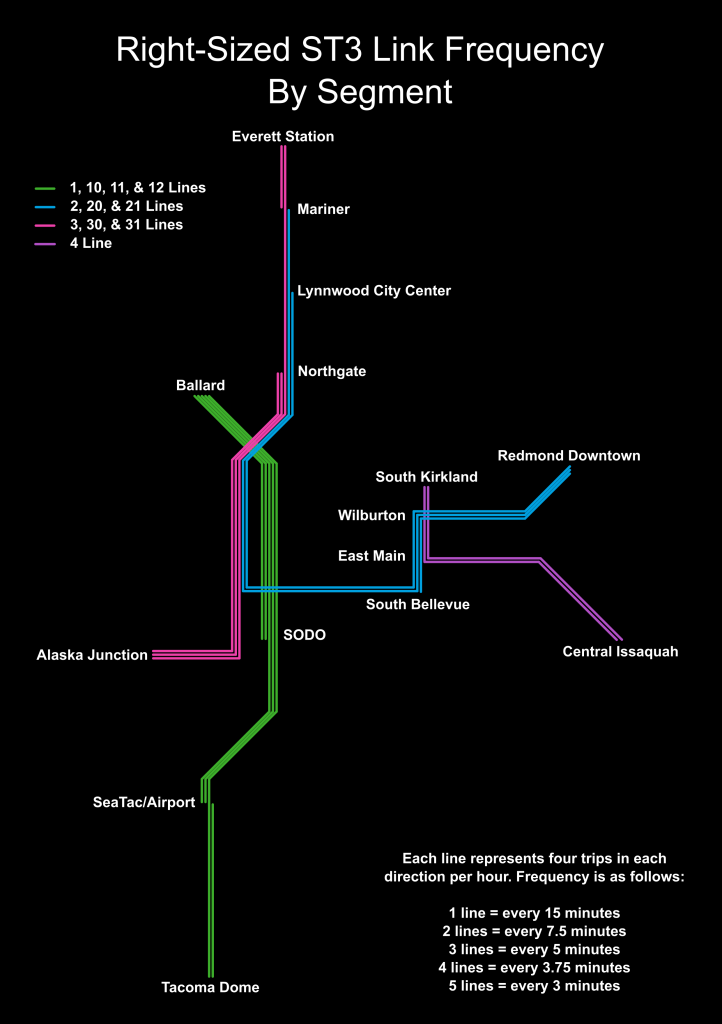

Rethinking the operating plan completely, as outlined here on The Urbanist in December, could eliminate the problems planners are facing with no extra vehicles and at rounding error cost increases while giving all portions of the system very good frequencies and appropriate capacity all day long.

Promising though is that the recommended hybrid approach Shelden highlighted leaves open the possibility that Sound Transit could further explore alternative service patterns to reduce vehicle needs. Whether or not that means a true rethink of the operating plan remains to be seen, but it increasingly seems that the agency is going to need to in order to avoid further ST3 delays.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.