One Seattle… *Some exceptions and conditions apply.

Today, the City of Seattle finally revealed its draft One Seattle comprehensive plan, which in some ways invited more questions than answers. The draft plan does not set zoning or firm boundaries between neighborhoods. Those details will need to come with the final plan due by the end of the year, which is in danger of coming in late because of delays to the planning schedule.

City officials said the Draft Environmental Impact Statement to accompany the plan will come out on Thursday, which will start the clock on the official comment period.

Whether the proposal plans for enough housing growth is an open question up for debate. Seattle’s growth strategy anticipates adding about 200,000 residents and at least 100,000 homes over the next 20 years. This would put Seattle’s population on the cusp of one million. It sounds impressive — though neighboring Bellevue’s plan adds enough capacity for 152,000 homes in its proposed growth strategy even working less than half as much land — through Bellevue’s 20-year growth target is officially 35,000 homes.

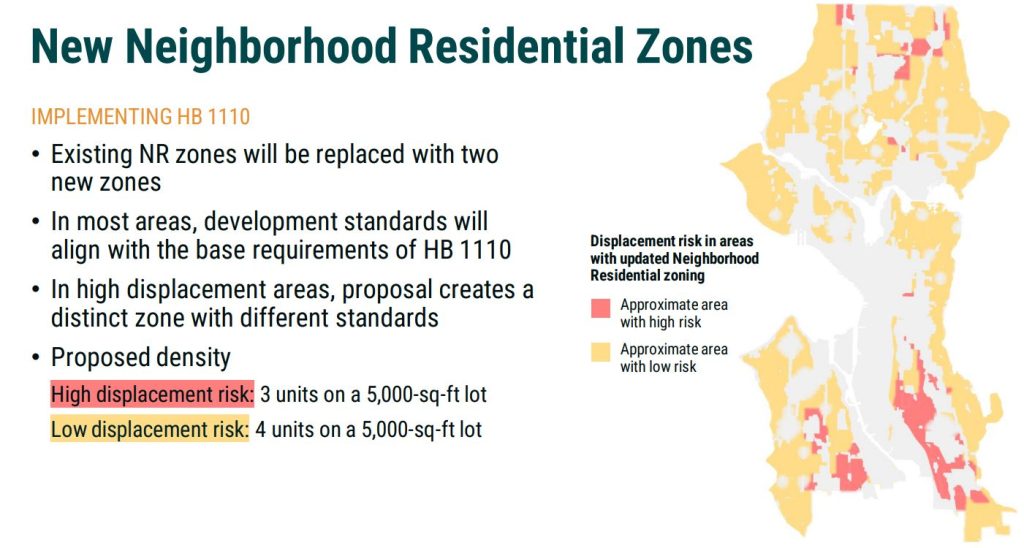

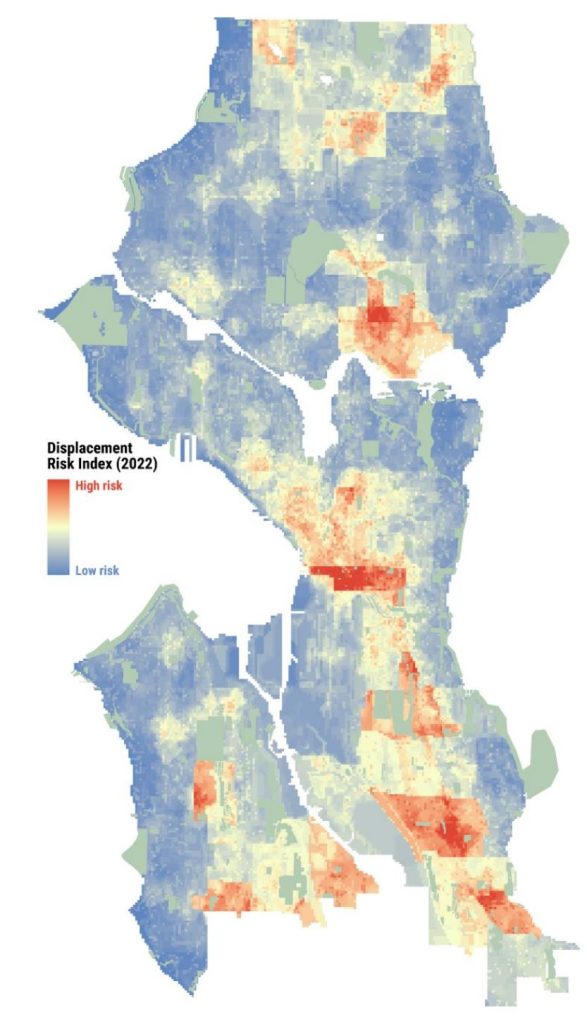

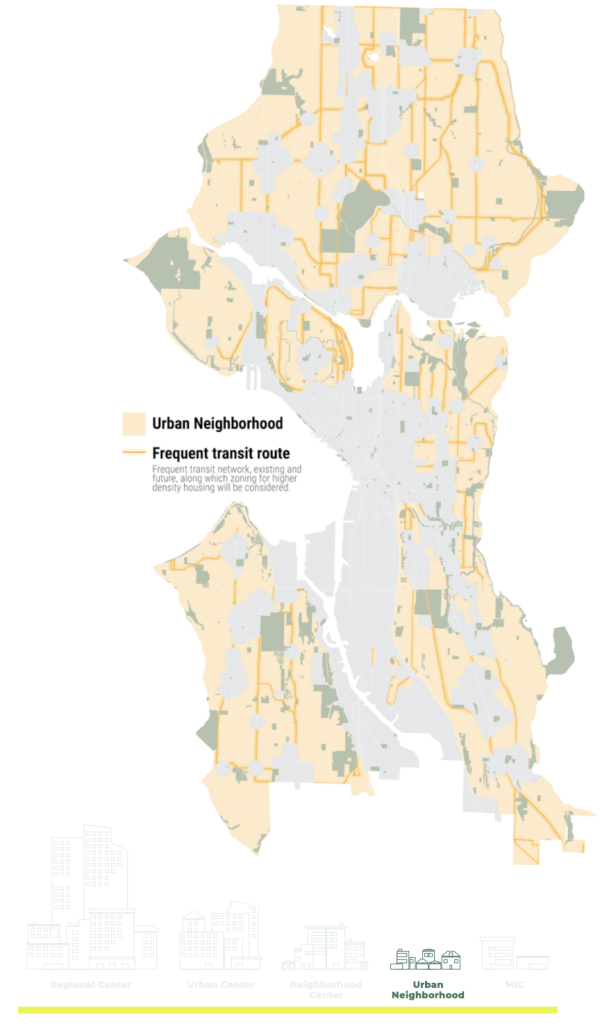

In a Monday rollout presentation and press briefing, staff from the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) revealed that the Harrell administration would be pursuing an exemption to the new state middle housing mandate (via House Bill 1110) for large cities to replace single-family zoning with fourplex zoning and sixplexes near frequent transit. In areas OPCD has identified as high displacement risk, the City intends to apply triplex zoning instead of what would otherwise be required.

The exact boundaries of this exemption area have yet to be set, but OPCD’s long-range planner Michael Hubner said it would be significantly less that the 25% of single-family zones that is the maximum adjustment state law allows. Perhaps 10% to 15% of Seattle’s remaining single-family zones could be included, which currently cover roughly two-thirds of residentially zoned land in Seattle. The areas set to be shielded from the new minimum density requirements include areas around Delridge Way in West Seattle, South Beacon Hill, a few areas of the Rainier Valley, and portions of North Seattle.

“Having grown up in the historically redlined Central District, I’ve seen firsthand how our city and the neighborhoods that make it special have changed as we’ve experienced rapid growth and increased housing costs, with longstanding neighbors, families, and small businesses too often finding affordability out of reach,” Mayor Bruce Harrell said in a statement. “This experience has informed my belief that we need more housing, and we need to be intentional about how and where we grow, addressing the historic harms of exclusionary zoning and embedding concrete anti-displacement strategies every step of the way.”

The Central District does not not appear included in the triplex exception zone. The displacement risk there does not spike as high as one might expect in City maps — perhaps because much of that displacement was past tense.

OPCD noted that they were not just seeking delayed House Bill 1110 implementation in the high displacement risk areas, as allowed in the bill, but seeking permanent zoning under the argument that is was complying at a lower density level. It’s not clear that the state will agree with that creative interpretation and may require Seattle fully implement the requirements down the road.

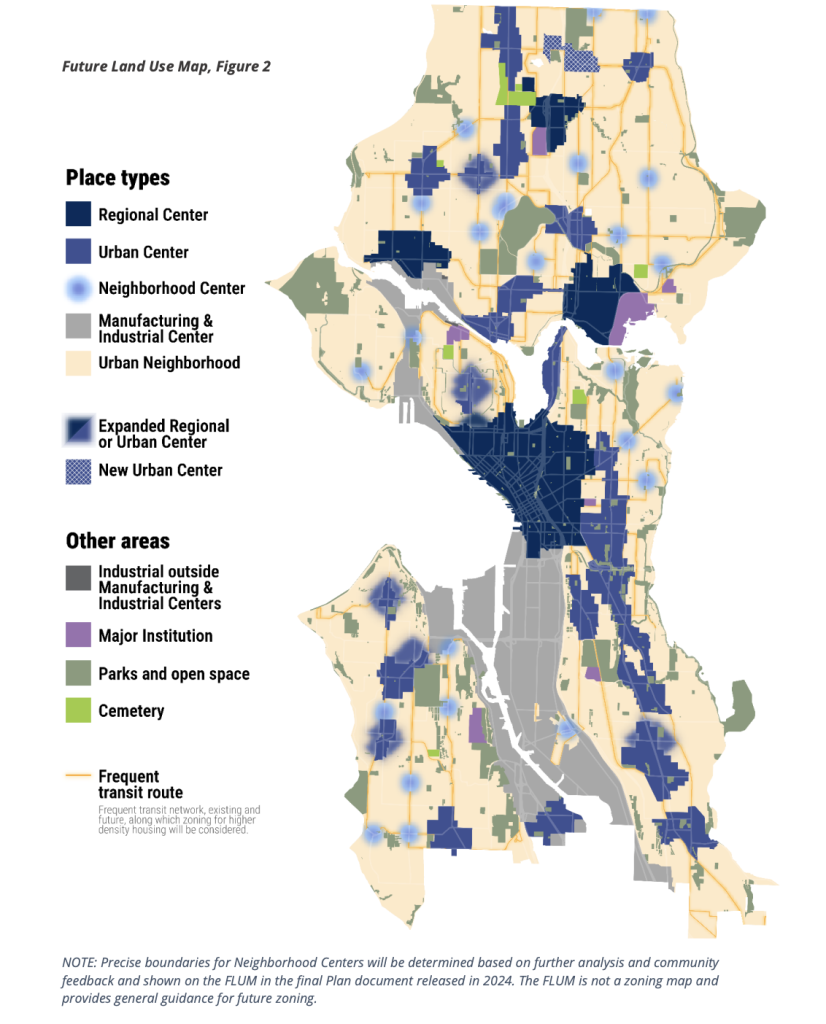

The One Seattle Plan has more of an urban branding, but it’s not yet clear if that will be matched in zoning and development regulations that actually encourage an urban transformation of Seattle’s largely single-family residential neighborhoods. The City plans to reclassify today’s “Urban Villages” to “Urban Centers” and today’s “Urban Centers” would become “Regional Centers.” Neighborhood Residential areas (formerly single-family zoned neighborhoods) would become “Urban Neighborhoods.”

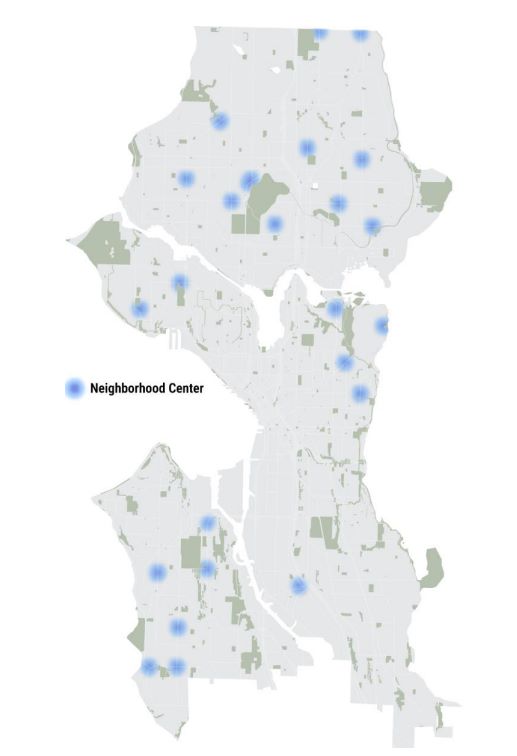

“Neighborhood Center” zoning treatment for 24 areas

OPCD intends to add a new designation called “Neighborhood Center” and apply it in 24 places, typically where an existing small commercial district provides an anchor for an urban neighborhood — in fact, they were called “Neighborhood Anchors” in an earlier scoping report, when OPCD proposed 40 anchors.

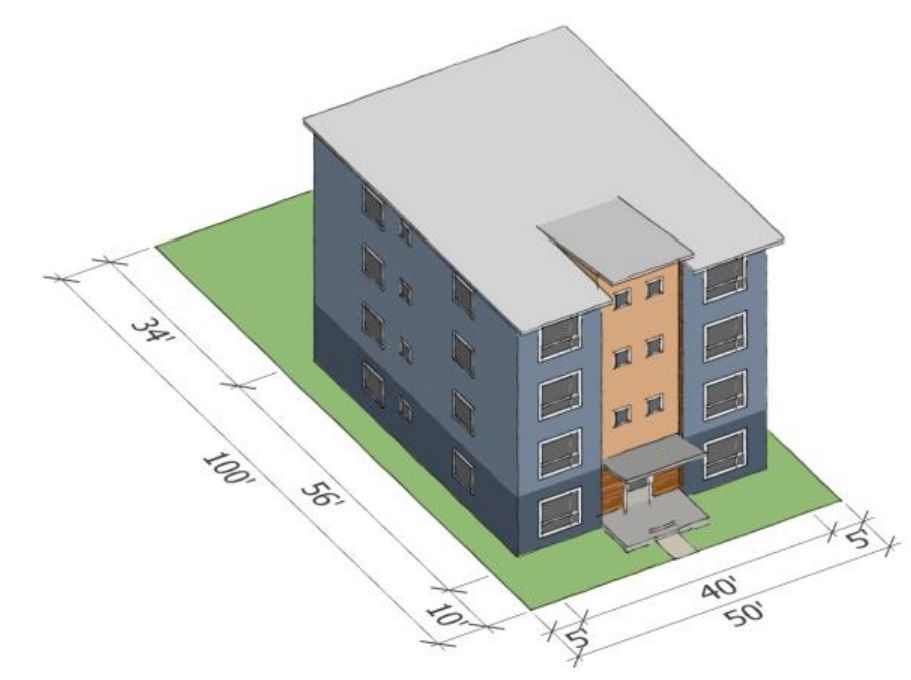

The “Neighborhood Center” designation (and ensuing zoning changes) would apply about 800 feet, or one to three blocks, from a commercial core, OPCD said. The City envisions some midrise zoning in these new Neighborhood Centers. “Zoning in these areas should generally allow residential and mixed-use buildings up to 6 stories in the core and 4- and 5-story residential buildings toward the edges,” OPCD’s growth strategy summary noted.

Proposed Neighborhood Center examples include Tangletown, Ravenna, Bryant, Wedgwood, Maple Leaf, Loyal Heights, Phinney Ridge, Southeast Magnolia, Fauntleroy, Madison Park, Madison Valley, Madrona, Montlake, Georgetown, Kenwood, and the area just east of Jackson Park Golf Course.

Among the 16 neighborhood anchors on the cutting room floor from the earlier proposal is one near Seward Park, where Mayor Harrell lives. Hillman City and South Beacon Hill were dropped from neighborhood anchor plans, as the Harrell administration looks to minimizing growth as an anti-displacement strategy. North Seattle accounted for seven of the cuts as its 18 neighborhood anchors in the scoping report were hacked down to 11. Laurelhurst and Broadview each drop two anchors, Maple Leaf and Wedgwood consolidate from two each to one each, and South Wallingford, Upper Fremont, West Woodland disappear from plans. The addition of Kenwood and southern Phinney Ridge partially offset those nine cuts in North Seattle.

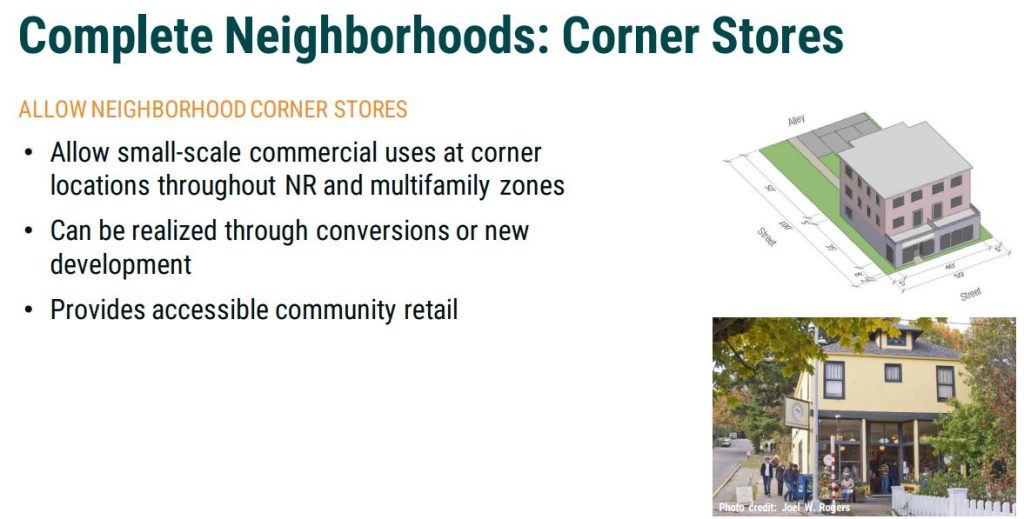

Neighborhood cafes and cornerstores

The draft plan proposes re-legalizing neighborhood cafes and cornerstores on corner lots across the city. This would open up small-scale commercial use opportunities in predominantly single-family neighborhoods where they are currently lacking. OPCD pitched this as part of a “complete neighborhoods” concept, also referred to as a “15-minute city” at times.

This session, the state legislature had considered making neighborhood cafes a statewide standard, but the legislation fizzled out and getting gutted in the state senate — facing typical local control arguments from the Association of Washington Cities. Seattle, fortuitously, is still looking to forge ahead with the concept. But the degree to which neighborhood cafes will actually be viable is not clear given the hesitancy to add real density to these neighborhoods.

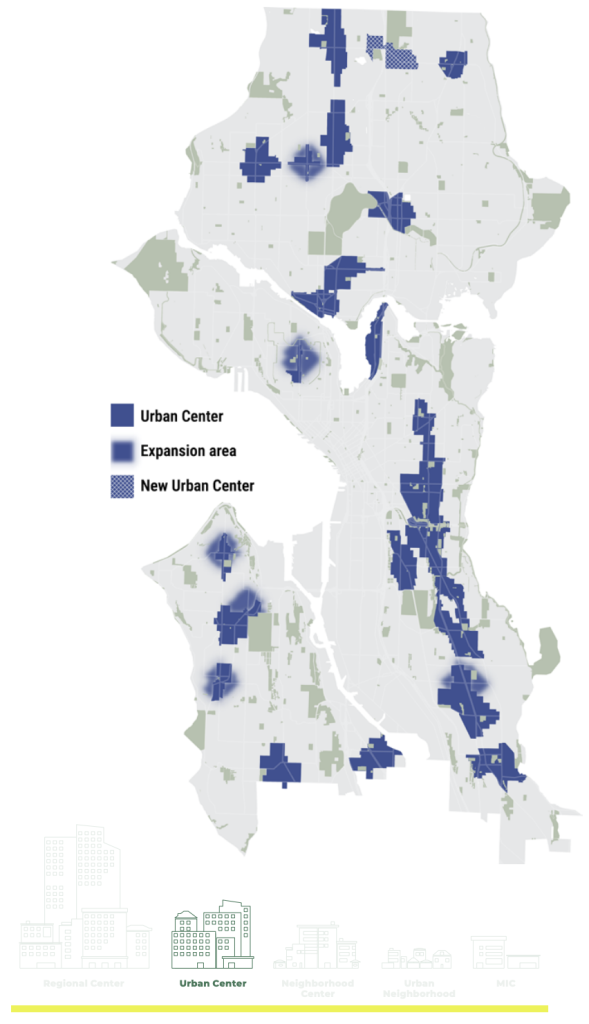

Expanding Urban Centers

With the name change from Urban Village to Urban Center, OPCD is also planning to expand the boundaries of some of the more anemic urban villages. This is an issue that The Urbanist has identified going back to 2015, when the last major update to the comprehensive plan was approved — without The Urbanist’s recommendation included at the time — along with adding more centers with mixed-use apartment zoning in areas most lacking urban vitality.

The exact extent of these boundary expansions is yet to be determined, pending the round of public outreach that OPCD is embarking on through March and April. However, their preliminary map indicates that they have Greenwood, Queen Anne, Admiral District, Junction, Morgan District, and Othello in mind for expansions.

Additionally, the City is planning to add an Urban Center around the planned NE 130th Street Station as promised to regional partners when Sound Transit approved the infill light station, set to open in 2026. Left out is the immediate area around the Shoreline North/148th Street light rail station, set to open later this year.

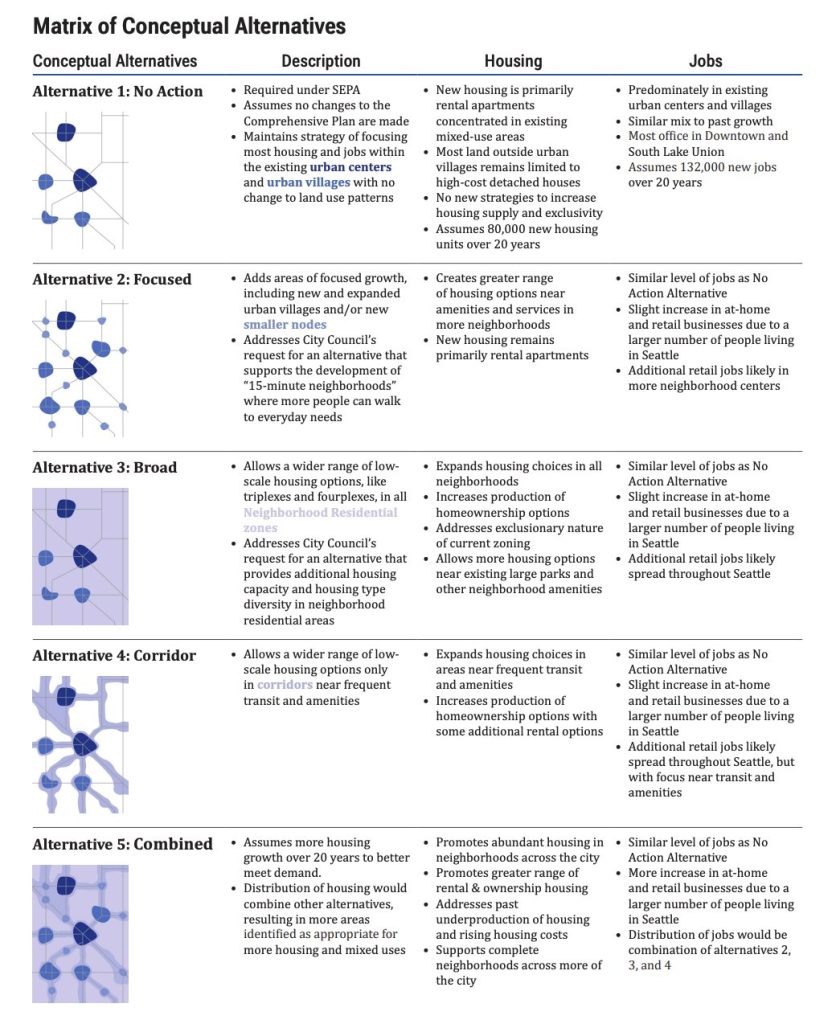

Mayor’s mix-and-match approach

Mayor Harrell’s spokesperson Jamie Housen said the mayor’s plan amounts to a mix-and-match from alternatives, but most resembles Alternative 5, which combined and stacked the other three main growth strategies studied (Alternative 2: focused within neighborhood centers, Alternative 3: broad multiplex zoning, and Alternative 4: growth corridors along transit).

“We looked at a wide array of options, right, these five different alternatives,” Housen said. “And we tried to pick from across these alternatives to get the best possible plan. So it’s not a one for one with any of those alternatives. It probably most aligns with Alternative 5 in terms of the many different things from that the menu of options we’ve selected, but it’s not a one for one with any of those.”

Alternative 5 has promised 120,000 net new homes over the next 20 years compared to 100,000 for the other non-baseline alternatives, reflecting the greater capacity the combined alternative would have compared to them. A coalition of housing advocates (The Urbanist included) had pushed the city to add an Alternative 6 to the study that shot for even higher housing growth and more density distributed across the city.

Growth target still lowball

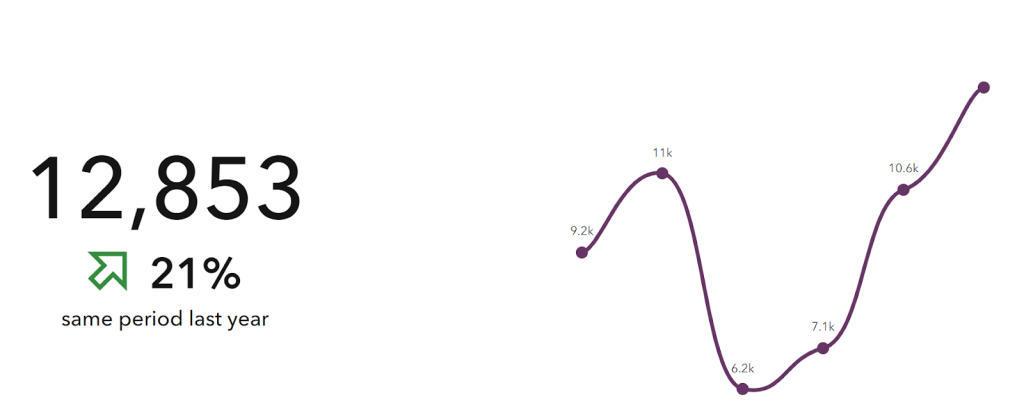

OPCD’s materials pledged the City’s plan would lead to “at least” 100,000 net new homes over the next 20 years. However, that pace of 5,000 homes per year is actually significantly slower as it has maintained over the last decade. In fact, Seattle added almost 13,000 new housing units last year, and exceeded 10,000 in three of the last five years.

Hubner said there is “no crystal ball” for what future growth would actually be feasible, he stressed that the planned figures exceeded the growth target Seattle was assigned by the county as part of the regional planning process.

“So when we say this plan will will will help us to add at least 100,000 units over the next 20 years, emphasis as is on at least because this these zoning changes will provide a lot of capacity. Our target under the Growth Management Act is only 80,000. That’s probably a lowball number,” Hubner said. “That’s why we’re growing to be a little bit conservative and just what we estimate we’re going to add but we want to be ready should the city continue to add a tremendous number of jobs into the future. And that’s why this plan adds a lot of new capacity. But the 100,000 exceeds our 80,000 target for the next 20 years. And we think it’s a reasonable number to be talking about what might happen during this planning period, but totally acknowledged it could be more and are ready for it.”

OPCD Director Rico Quirindongo said the City is aiming to create larger, family-sized homes and hoping to increase the city’s average of residents per home. He also hinted that housing growth would cool off if job growth tapered.

“So when we’re projecting 100,000 units for the next 20 years are at least accommodating that as a baseline,” Quirindongo said. “We know that that’s going to accommodate more than 200,000 people. And what we know is if we look at what the Puget Sound Regional Council told us — ‘you must provide this many houses’ — we actually have been providing more than that baseline. And it just so happens that our job growth has also exceeded the Puget Sound Regional Council original projections. So we’re just trying to keep up with ourselves.”

Over the past decade, new apartments have increasingly trended toward one-bedrooms or studios, but OPCD seems to be predicting a reversal and a shift to multi-bedroom units. Some countervailing trends remain, though. Early this week, the legislature gave final approval to a bill that will require all cities to allow micro-apartments with shared kitchen facilities, a housing type that the City of Seattle has all but completely regulated out-of-existence.

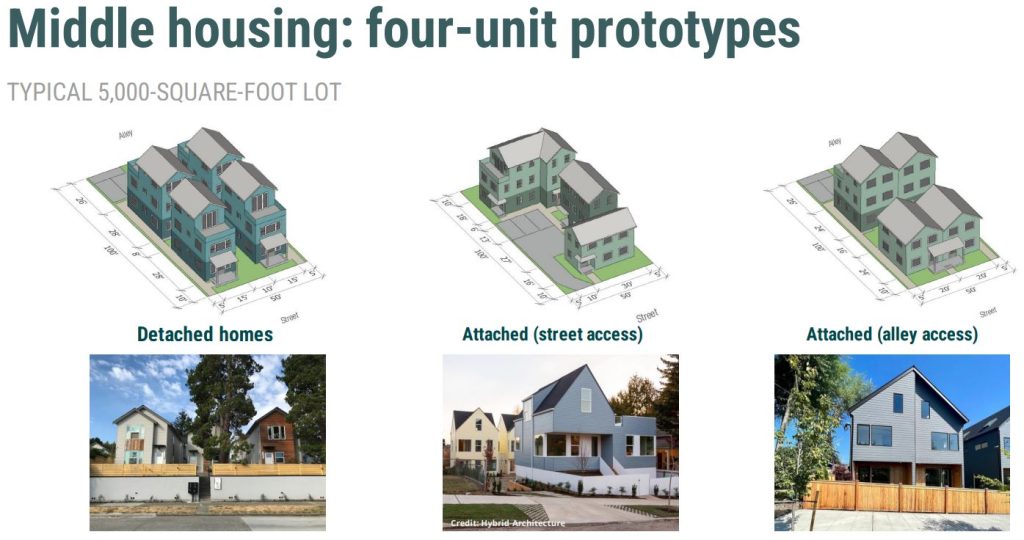

City plans for fourplex townhomes rather than sixplexes

Future development in the new Urban Neighborhoods would be dominated by fourplex townhomes, according to OPCD planning and projections. Staff said that most Neighborhood Residential blocks are not within the a quarter-mile walk of qualifying frequent transit that would kick in the state’s sixplex zoning standard. And OPCD is not planning to exceed that standard for more areas of sixplex base zoning.

OPCD’s Brennon Staley is leading the effort to turn the plan into zoning policy, and he indicated the City’s discussion with for-profit developers has indicated townhomes are a more popular product for the typical 5,000 square foot Seattle lot in Neighborhood Residential zones.

“There’s a real preference for having people only from the ground to the sky,” Staley said. “And once you get to a certain number of units, those floorplates get really small, and they don’t become livable. So I think that what we’re hearing from initial analysis from the developer community is that they want those floorplates to be appropriate for like a two-bedroom or three-bedroom unit. And at a certain point it doesn’t work to try and fit in so many of them on a lot.”

Interestingly, this analysis contradicts that of some urbanist-minded homebuilders. Architect Matt Hutchins created a “Seattle Sixplex” design that he said could be a template for redeveloping the typical Seattle residential lot. However, since Spokane was quicker to amend their zoning to promote multiplexes, Hutchins is building his test case sixplex in the Lilac City instead of the Emerald City. Hutchins has argued that without hitting the sixplex tipping point where it is economically feasible to redevelop — weathering Seattle’s laborious and fee-laden permitting process — the dominant new housing product in formerly single-family zoned areas may simply be larger single-family homes, with some additional accessory dwellings and backyard cottages added in the margins.

As a stacked flat rather than a townhome product that subdivides the land for each townhome owner, a sixplex would require selling the units as apartments or condominiums, which comes with added hurdles in term of regulations and financialization. The American housing system is heavily weighted toward fee-simple transactions that allows a homeowner to take out a mortgage and a developer to cash out immediately. On the other hand, liability laws and limited investor interest discourage new condos; plus, multifamily builders have been focused on large developments rather than missing middle projects, especially those adding just four or six homes at a time.

In other words, a boom in sixplex flats would be novel and speculative and it’s hard to predict the likelihood of such a sea change in Seattle’s housing industry. Developers and the investors that fund them are notoriously conservative and hesitant to jump on new business models, which are inherently unproven and risky.

However, if someone cracks the code to build stacked flats on 5,000-square-foot formerly single-family lots at scale, it could suddenly become the product of choice. A sixplex can deliver family-sized units and have a shared single stairwell that cuts down on wasted circulation space and skinny floorplates that tend to come with three- or four-story townhomes.

The Harrell administration doesn’t appear too keen on exploring that possibility, however. Their vision at this juncture appears to be more “four-pack” townhomes. The question of whether Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements will apply to the new fourplex and sixplex zones also remains unsettled, with OPCD staff indicating they’re not included at this point, but not ruled out either.

Affordability bonuses

While OPCD was highly skeptical that for-profit developers would pursue stacked flats, they were bullish that nonprofit affordable housing builders would jump on the opportunity to build them. In fact, they previewed an affordability incentive floor bonus that goes beyond what is mandated in HB 1110, potentially allowing eightplexes or higher.

Encouraging affordable housing development in formerly walled-off single-family zones is wise, but it’s not likely to scale quickly and approach the same volume private developers could given the right opportunity. Leaving stacked flat production to nonprofits and not even trying to explore a market-based model could be a tactical miscalculation, especially for an agency that admits it’s lacking a crystal ball to predict the future.

Even if we cannot predict outcomes with perfect confidence, policy decisions can shape the future to the point of being a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially if we prematurely foreclose on entire realms of possibility — which has much to do with our housing crisis was manufactured in the first place.

The City has an online engagement portal at engage.oneseattleplan.com. OCPD has also planned a series of eight outreach events starting at Loyal Heights Community Center on March 14. The open houses move around the city before the last scheduled outreach event, which is a virtual open house at 6pm on May 2.

Correction: The original version stated Bellevue anticipates adding 225,000 residents over the next 20 years. That was inaccurate. Bellevue’s plan adds capacity for 152,000 additional homes, but does not expect most of those homes to arrive in the 20-year timespan. Over that span, Bellevue officials expect housing growth to be closer to the 35,000 target given them by the county. The growth target language has been removed from the headline and relevant paragraph.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.