The idea of “regionalism” and how the elected officials tasked with leading Sound Transit can come to consensus to achieve regional goals was front-and-center when the Sound Transit board of directors held an all-day retreat Thursday at Everett Station.

With a new interim CEO, Goran Sparrman, at Sound Transit’s helm and four brand new board members still finding their footing, the day served as a level-setting session and a standard get-to-know-you team building event. But a focus on realigning the agency, charged with implementing a $149 billion capital program through 2046, with a broader vision for the overall Puget Sound region provided an additional element that could signal a shift in how decisions at Sound Transit get made.

One of the first presentations that the 14 members of the board present Thursday received was a brief timeline of the agency’s history since its founding in 1993, including milestones like the approval of Sound Move (the agency’s first ballot measure) in 1996, the start of Sound Transit express bus service in 1999 and the approval of the ST3 ballot measure in 2016. King County Executive Dow Constantine, the current board chair, referenced a need to get the way the board operates back to looking more like a prior era.

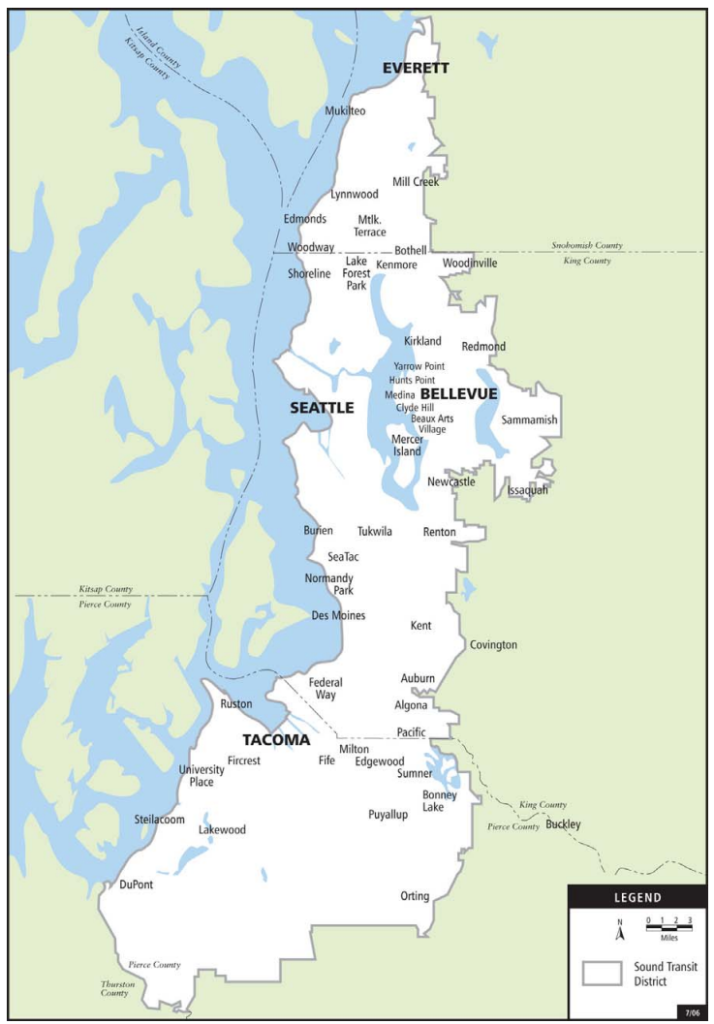

“My observation is that this board used to be a bit better at maintaining that regional lens,” Constantine said. “We were, in the earlier days, able to really think about the entire system, and as time has gone on, there’s been a little bit of a retreat into localism.” A significant source of that localism certainly comes from members in corners of the Sound Transit taxing district, where residents have been paying into the system for decades, clamoring for the light rail “spine” to finally be completed. The meeting Thursday was held in Everett, a symbolic choice of a city that won’t see Link light rail service in downtown until 2041 under current plans.

Of course, things can always look more rosy in retrospect. In 1999, when the Sound Transit board was selecting a preferred route to get to Northgate via the University of Washington, board members from outside Seattle voted down a proposal supported by Seattle Councilmember Richard McIver and King County Councilmember Greg Nickels — not yet Seattle’s Mayor — to study a second station in Capitol Hill, around Roy Street. In retrospect, that station would be more valuable than infill stations like Graham Street or Boeing Access Road, but it’s impossible to achieve now.

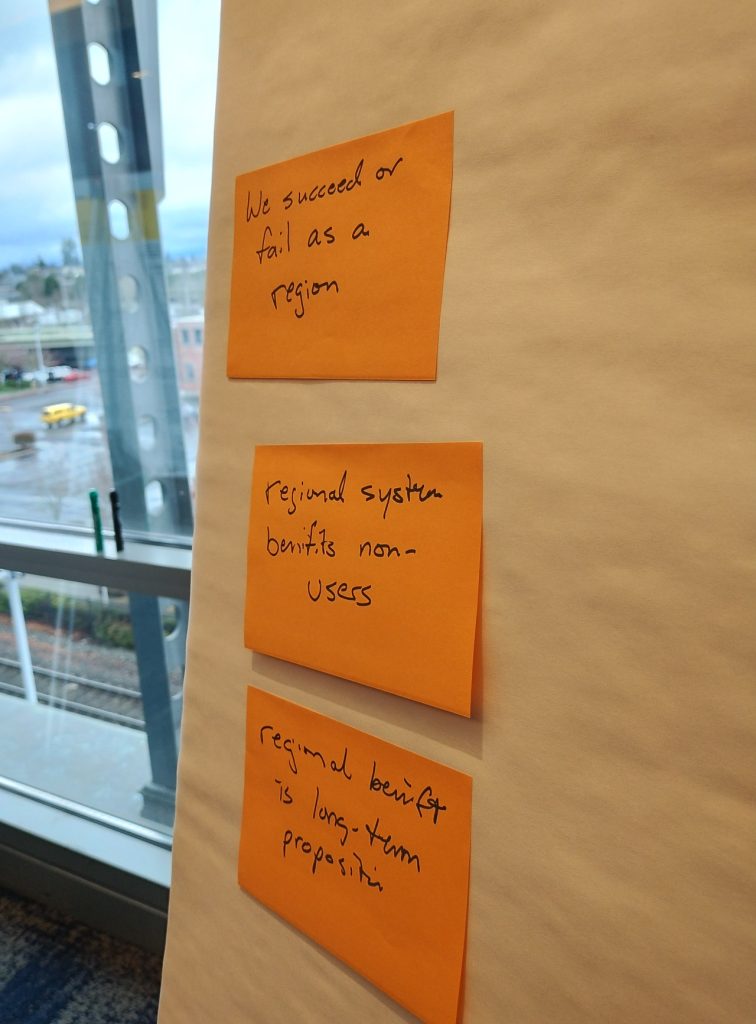

“Every project and action the board takes gives us an opportunity to weigh tradeoffs, to seek leverage opportunities, and there’s a lot of pressure to kind of run to our corners or choose upsides,” Constantine said. “And we just have to find ways to resist that and look for the commonality, and for each of us to own the success of every project and every extension and every destination.”

But Pierce County Executive Bruce Dammeier noted the inherent difficulty in trying to do that as local elected officials. “We have to acknowledge that our jurisdictions are distinct and individual, we have to allow some ability to address the local needs, but without it overriding our regional responsibilities. And therein lies the tension.”

It was King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci who noted that regionalism can mean very different things to different people. “My vision is that we need to build the system that works best for the riders throughout the system,” Balducci said. “That works the best for the riders,” she emphasized.

Balducci positively referenced the tunnel underneath downtown Bellevue as a decision that was made with regional interests in mind, even though it was the subject of intense debate within Bellevue. It was Balducci who brought up an issue that the board currently faces that does put regionalism front-and-center: a decision on where a second tunnel station in Seattle’s south Downtown, a transfer point for riders heading to and from the Eastside, should be located.

“Some of those decisions are harder. Recently we’re having a very difficult discussion about what to do in the CID [Chinatown International District], and the option that we’re talking about right now doesn’t work great regionally, I’ll just be honest with you.”

The late-breaking option to skip Chinatown, promoted by Constantine and Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, would bypass the natural transit hub that is King Street and Union Stations in favor of stations quite a significant walking distance away to the north, near Seattle City Hall, and to the south, near the stadiums. That “North and South of CID” option is now officially preferred by the board. A shallow tunnel underneath 4th Avenue S that would retain a transfer hub directly around Jackson Street remains on the table, but as a secondary alternative facing procedural hurdles to get reselected as preferred. (Harrell was one of the four boardmembers absent from the retreat.)

In discussing how to further regional goals, Balducci took things a step further — “put[ting] our money where our regionalism is,” as she phrased it — and suggested that the transit agency’s current policy of “subarea equity” might not be furthering regional goals. That internal policy at Sound Transit dictates that funds raised within five areas inside the region — Pierce County, South King County, North King County, East King County, and Snohomish County — must be spent in that area, with some exceptions. “If it’s a regional system, why do we have that policy? Why don’t we just pay to build what we need to build in the whole system,” she asked rhetorically.

Snohomish County currently contributes the lowest amount of dollars to its subarea out of the five, while the planned Link extension to Everett is one of the most overbudget in the plan. Yet the board seems reluctant to explore ways to both cut costs on the project and provide a better transit line. On the other hand, Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers has shown a cost-cutting interest when it comes to stations in Downtown Seattle, even proposing to abandon a station planned in South Lake Union.

Seattle Councilmember Dan Strauss, new to the board in 2024, went so far as to suggest that subarea equity had actually backfired and was creating current problems.

“It would honestly be easier for me to work on the West Seattle and Ballard lines, had we connected to Everett and Tacoma,” Strauss said. “And the reason it would be easier for me, for Ballard and West Seattle, is because we would be able to keep that long-term vision in mind, where putting a tunnel in West Seattle sounds scary, putting a tunnel in Ballard sounds scary, it sounds scary because of the dollar figures that are associated with it before we completed the spine.”

With that long-term vision, Strauss said, the agency would be able to start thinking about what comes beyond ST3 projects. “And it’s the best long-term solution for those neighborhoods, because after West Seattle, [the line] goes down to White Center back to Renton, after Ballard it goes through Crown Hill, back to Northgate. But it is hard to have that conversation today, because we haven’t gotten to Everett and Tacoma.”

Of course, regionalism doesn’t just mean preventing tunnel vision when it comes to future projects, it also means going back and fixing mistakes from prior eras. King County Councilmember Girmay Zahilay, another new board member, has brought renewed attention to the myriad of issues stemming from running Link at grade along MLK Jr Way S in Seattle, both for Sound Transit and the broader community. The coming months will show just how much attention the rest of the board is ready to give that issue, even as track blockages are set to impact riders in their communities.

“I really think that recapturing that regional spirit, and being able more frequently to don our regional caps, will allow us to have more success in each of our own projects,” Constantine said.

Time will tell whether redoubling an effort to look at how we make transit decisions more regionally will allow the board to gear its decisions more toward the benefit of riders than political expediency or side benefit.

Correction: A previous version mistakenly dated the Sound Move vote to 1993. That ballot measure happened in 1996.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.