King County Metro’s RapidRide enhanced bus program gets a lot of praise for what it gets right: service frequency, span of service, and speed. Ridership has responded with significant increases on some upgraded local corridors over the years; some routes saw their ridership nearly double. Naturally, King County Metro and local officials see this as a success story and have made it a central priority for investment with seven currently operating corridors and six more in the pipeline.

The problem, however, is that the agency has been very slow to deliver new RapidRide routes, watching costs balloon in the process while showing limited ability to keep a handle on projects.

In response to the pandemic, King County officials moved to partially put a pause on RapidRide network build out, suspending project development of the RapidRide K and R Lines slated for Bellevue, Kirkland, and Southeast Seattle. Only projects that were well into design and construction such as the RapidRide G, H, I, and J Lines were kept moving forward, in part due to partner agencies. This came after Metro and Mayor Jenny Durkan’s 2018 decision to nix planned RapidRide upgrades for Routes 40, 44, and 48 that had been pledged in the Move Seattle Levy to be delivered by 2024 — which was in response to transit grants largely drying up during the Trump administration.

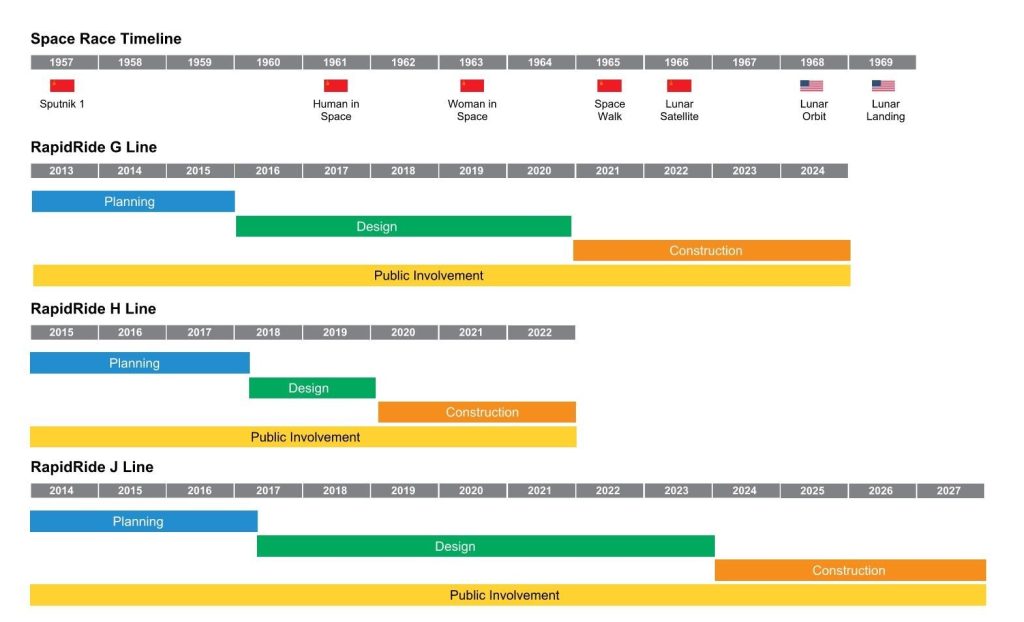

RapidRide projects: slower than the space race

The timeline for planning and design of the surviving RapidRide projects, however, is staggering even accounting for pandemic delays. Seven years for the RapidRide I Line, eight years for the RapidRide H Line, 12 years for the RapidRide G Line, and 14 years — currently projected — for the RapidRide J Line. The RapidRide K and R Lines, now advancing deeper into early design, are still years away with best case opening scenarios of 2028 for the R Line and 2030 for the K Line — at least eight to ten years of project development and construction.

The space race was wrapped up in 11 years, and that was an effort of extraordinary complexity and technical skill — requiring literal rocket scientists. Purchasing buses, painting bus lanes, and installing transit signal priority is, by comparison, a very simple task. RapidRide deployment unfortunately epitomizes how our administrative state capacity has become completely strangled by process and self-made roadblocks.

Building a cohesive network, don’t piece-meal it

The dirty secret of RapidRide is that, at its core, it’s cheap, quick, and easy to implement — if we dispense with all the bureaucratic effort to secure federal and state grants and carry out repetitive block-by-block street fights which delay those grants. Those fights often lead to local jurisdictions jettisoning bus lanes and queue jumps, anyway, which are a key feature to deliver the “Rapid” part of the service.

Metro could deliver a complete “RapidRide” network in the time that a single RapidRide project takes to complete by making smarter policy decisions and implementing them in mass:

- Building new and expanded bus bases;

- Procuring new buses to expand the fleet;

- Increasing service levels and restructuring bus service consistent with the Metro Connects long-range plan;

- Taking pragmatic actions to improve speed and reliability (e.g., bus stop balancing and installing targeted painted bus lanes, queue jumps, and transit signal priority in willing communities); and

- Further investing in labor (e.g., better wages, benefits, and rights) and modernizing recruitment and training processes and infrastructure.

Investing at scale in a network would prevent the absurd situation like we are seeing with the planned RapidRide G Line rollout this fall. Metro promised six-minute bus frequencies until 7pm in its grant application so that’s what it’s aiming to deliver, but doing so required some awkward tradeoffs due to the scarcity of Metro service hours. First off, G Line frequencies plummet to every 15 minutes after 7pm. Furthermore, to scrounge up the hours, Metro also slashed service on neighboring routes, particularly on Routes 10 and 49.

Instead of Seattle seeing a vastly improved network as a big new investment more than a decade in the making comes online, it will see one route that is really good until 7pm and a network that is cobbled together with duct tape and prayers — worse than before for some riders.

Funding a real bus network

Now, to make a network approach happen, it is going to take additional capital and operating funds. There’s no getting around that. But the primary tool is the same one that building out a smaller RapidRide network requires: a countywide sales tax and/or car tab fees.

For years, the King County Council has flirted with the possibility of putting a countywide funding measure to a public vote. But constrained Metro capacity and timing alignment with Seattle’s transit taxes before the pandemic and reduced service levels due to self-inflicted staffing shortages and lower ridership since the pandemic have led officials to hold on acting.

Ridership, however, continues to rebound and Metro has begun to stabilize service with an eye toward increasing as staffing resources allow. Now is the time to start developing a countywide measure. But doing that may require real fortitude and willingness to rethink priorities.

For many elected officials, running more bus service everywhere instead of a small number of RapidRide lines might not be as politically appealing due to the lack of flashy groundbreaking photo ops and cut ribbons for newly christened bus lines. But the truth is that more frequent and reliable service is what riders really want and what climate action demands. We can’t wait decades for Metro and local communities to get their act together and for federal, state, and local funding to come through for RapidRide.

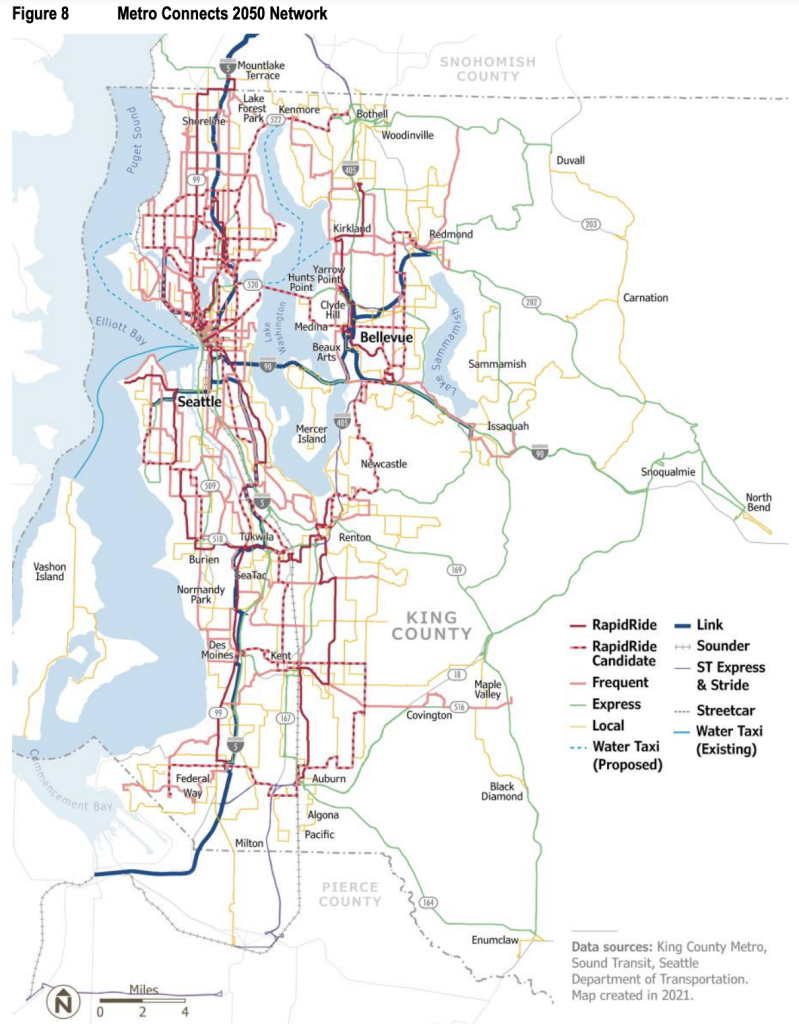

Metro Connects is an ambitious plan that seeks to increase annual service hours from four million to just over seven million by 2050 countywide. We can absolutely achieve that — and much sooner if we are willing to make wise policy choices. But we are unlikely to achieve that if we stick with lofty RapidRide goals.

That’s because Metro Connects’ capital program vision will take $28.3 billion to realize — a likely underestimate with the way capital expansion projects have been going in Puget Sound with cost overruns hitting 40%, 80%, or more above anticipated costs. Forecasted revenues are only expected to cover $10.3 billion of that vision, leaving at least $18 billion unfunded. We can’t count on transit-friendly federal administrations like President Biden’s to be around to fill that gap, and the state has not shown a serious willingness to fund public transportation — even in the latest statewide transportation package. We’re basically on our own.

And while the new RapidRide H Line — opened last March — is a welcome addition to the transit network, it illustrates how RapidRide is a resource hog. Not only did it nearly take a decade to realize, project costs for just 12 miles of bus service totaled over $154 million and required numerous partners to kick in funding for it. The vast majority of that money was expended on purely discretionary project elements. That includes things like street beautification, utility upgrades and replacement, new medians, and installation and rebuild of non-transit transportation facilities as well as common off-board infrastructure at RapidRide stations — while they’re very nice to have, they’re not completely necessary. Only about 20% of the corridor saw new bus priority lanes.

Likewise, the RapidRide I Line between Renton and Auburn via Kent is expected to top $160 million and only 5% of the 17-mile suburban corridor will see business access and transit (BAT) lanes. And the RapidRide J Line, which spent a decade in planning and design, saw half of its corridor lopped off to deal with funding constraints. The extra mile of bus priority lanes — almost exclusively through BAT lanes — in each direction will undoubtedly be welcome but are virtually all painted on existing streets, which should raise eyebrows for the eye-popping $120 million cost estimate.

We are therefore left with a binary choice: a much more frequent, expansive transit service network this decade or a modestly more frequent, expansive transit service network many decades from now.

We know that a large-scale expansion of RapidRide will drain resources and delay much needed transit expansion in King County. It’s time to reprioritize and put our efforts behind a fast rollout of countywide service expansion at an affordable cost now so that nearly everyone can have ten-minute or better service most of the day. Riders and the climate will thank us if we do.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.