The Harrell administration has released a finalized version of the Seattle Transportation Plan, the 20-year vision for the citywide transportation system that it has been developing over the past two years. The plan will significantly inform the transportation element of the city’s Comprehensive Plan that is due at year’s end, with the complimentary land use plan — how and where Seattle will add housing and jobs — now delayed nearly a full year behind its initial release schedule, with a draft now pledged in early March.

Clocking in at about 750 pages plus appendices, the plan will now head to the Seattle City Council’s transportation committee. With four brand new members, that committee is still generally getting its hands around the workings of city government and the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) in particular. Significant tweaks aren’t likely, though any that do get made do have the potential to provide insights into policy priorities for incoming councilmembers.

The lofty plan includes eight overall goals for Seattle’s transportation system including safety, equity, and “maintenance & modernization,” as well as a long list of “key moves” under each priority. It sets itself up as providing a framework for transportation priorities through 2044, but other more tangible events coming up will do much more to actually set the agenda for the foreseeable future when it comes to SDOT spending and action. The most significant one is the renewal of the Move Seattle Levy this fall, with SDOT’s forthcoming release of an updated Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP) close on its heels.

Accounting for at least 30% of SDOT’s overall budget, the Move Seattle Levy will determine how much the City has on hand to spend on transportation over the next nine years — and how much it’s able to leverage to take advantage of outside grant opportunities. The TAMP will tell us where maintenance dollars will be best used, another significant opportunity to leverage investments. Knowing which streets are most in need of repaving, for example, will dictate which corridors can be upgraded to make them safer and more accessible at the same time. It’s with those projects where the high-level vision outlined in the Seattle Transportation Plan will be actually put to the test.

Right now, SDOT is developing two potential sets of budgets for next year — one if voters approve a new levy, and one if they do not. But it’s still not clear what positive vision is being put forward.

High-tier projects for deadly roads like Aurora, Rainier

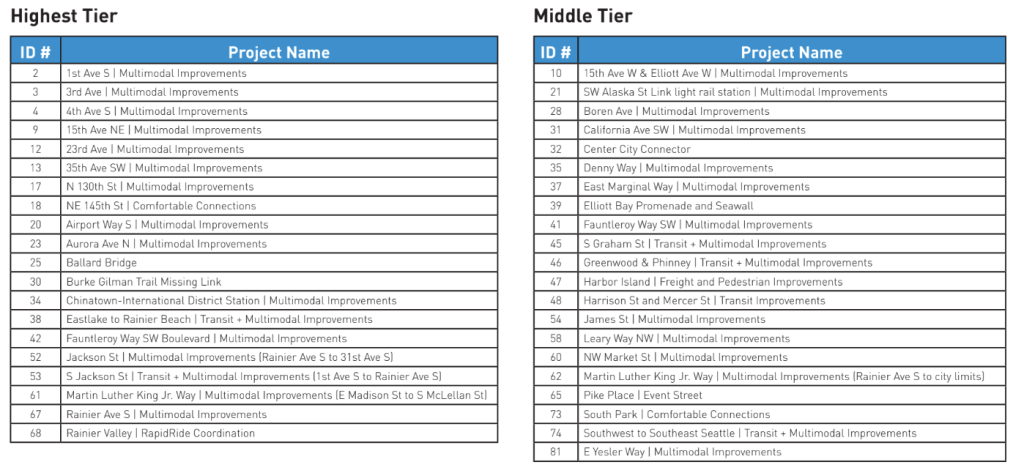

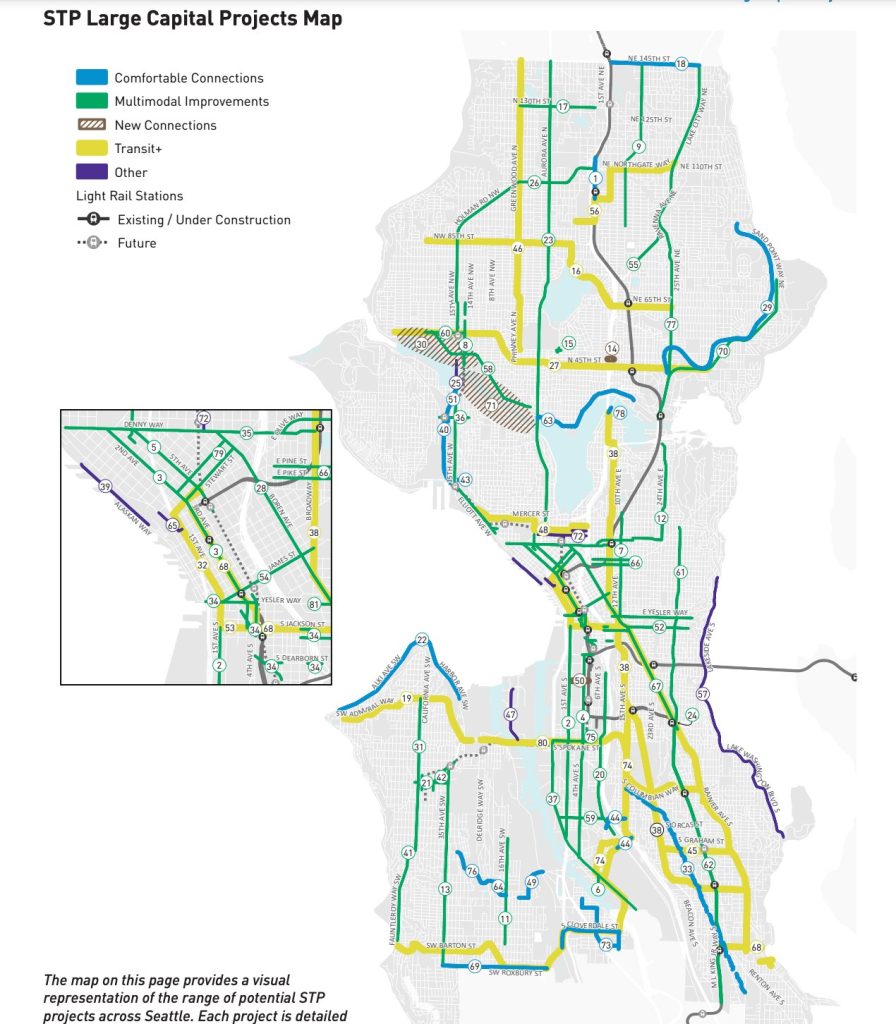

The STP released today includes more fleshed-out details on the 80 or so projects that SDOT sees as in line with the 20-year vision for the transportation system, but it still doesn’t include any prioritization of those projects. Next year, the department says it plans to release an implementation plan for the STP, based on available funding. This plan, however, does include a broad ranking of projects into three “tiers”, providing an insight into what projects could provide the biggest return on investment. The list won’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the city’s most dangerous streets, and includes projects like First Avenue S and Fourth Avenue S in SoDo, Rainier Avenue S and MLK Jr Way S, and Aurora Avenue N.

Many of these streets are the same ones where improvements were touted in 2015 to pass the current transportation levy, providing a good lesson in the fact that a list of projects is easy to make; implementation is the hard part.

With some early signs that the Harrell administration is leaning toward a levy renewal that totals $1.2 billion, the total of 2015’s levy simply adjusted for inflation, to be used against a transportation system with a replacement value of $40 billion, the need to target investments likely can’t be understated. Mobility and climate advocates, for their part, have called for a $3 billion levy focused on street safety and transit, a clear attempt to shift the City’s thinking about tackling its biggest challenges.

What’s changed since the draft plan

If you dug into the plan when it was released last summer, you may be wondering how it’s changed in response to added public comments and a thorough review by Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office. The answer is not much, perhaps unsurprising given the sheer size of the plan. The plan does now include a formal vision statement, as flat and broad as possible in hopes of mass appeal.

“Seattle is an equitable, vibrant, and diverse city where moving around is safe, fair, and sustainable. All people and businesses can access their daily needs and feel connected to their community,” the statement reads.

The final plan emphasizes the importance of economic vitality more than the initial draft. We can trace this back to feedback received by business advocacy groups, including the Seattle freight advisory board. A letter that board sent last October requested that change, at the same time that it recommended the entire plan be held back so that it can be evaluated against the broader plans for changes in Seattle’s land use that are set to be included in the Comprehensive Plan update. “The Draft STP does not meet the goal of a holistic planning document,” the letter stated.

That request echoes criticism of the STP from the Seattle Planning Commission, which reviewed the plan in depth last year and sent SDOT a laundry list of suggested ways to beef up the draft, with coordination with the Comprehensive Plan near the top of the list. “Transportation investments to serve future land use development patterns will depend on the selected growth strategy and housing and jobs projections in the Comprehensive Plan,” their feedback noted. Likewise, Seattle Neighborhood Greenways stressed the opportunity to advance the 15-minute city concept by pairing denser land uses with building safe infrastructure for people walking, rolling, and biking. Advocates on all fronts want to see more on how the plan actually gets implemented.

The updated plan released this week does include some additional details, though vague, about how the land use plan the City is developing will interact with the STP. The type of neighborhood, whether “high density,” “low density,” residential, or industrial, are said to guide the types of investments the City will be making over the life of the plan.

“Many existing low density, primarily residential areas will evolve into ‘complete communities’ with more urban places as part of Seattle’s growth strategy,” the plan now states. “To align with the directed growth in these places, investments in frequent bus transit are a priority. Investments may also include community and mobility hubs. For pedestrians, we will maintain and, in some cases, enhance our sidewalk infrastructure.”

“In manufacturing and industrial centers (MICs) — the Ballard-Interbay Northend (BINMIC) and Greater Duwamish MIC — freight mobility and access are emphasized,” it states. Industrial areas like SoDo see some of the highest rates of fatal and serious crashes in the entire city, with business interests often adamant about not seeing any improvements installed that could impact freight movement. “Moving freight is complex, but safety for all people — whether driving trucks, biking to jobs, or walking to a transit stop — comes first and foremost.”

Since 2020, there have been signs that SDOT would be transitioning to a land-use based framework for prioritizing projects in an attempt to resolve conflicts over “scarce” street space, even though ultimately street space — which takes up nearly a quarter of the land in Seattle, is not scarce at all. This has always been a dicey proposition, since fights over which modes to prioritize are at their heart political, and not technical. The Seattle Transportation Plan could represent a step backwards, taking the city away from ambitious network goals like those included in the Bicycle Master Plan. Or it could turn into a plan that sits on a shelf.

Turning the Seattle Transportation Plan’s vision statement into action that furthers city goals across the board, as it sets out to do, will take political will and follow through.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.