On Tuesday, the Washington State House of Representatives passed a bill intended to open up new development capacity around the state’s most robust public transit infrastructure. House Bill 2160 would require cities to allow larger buildings within a fairly wide area directly around light rail, commuter rail, and streetcar stops, and slightly smaller buildings in areas directly around stops on bus rapid transit (BRT) lines. It also allows affordable housing developers to build taller if they include more units in their buildings that remain dedicated for low-income residents.

The bill represents some unfinished business from the 2023 legislative session, when Governor Jay Inslee signaled strong interest in seeing a transit-oriented development (TOD) bill pass during the widely-touted “Year of Housing.” But ultimately, no bill was able to pass both chambers after it became clear that there were some big policy disagreements between the House and the Senate when it came to essential elements of a TOD bill.

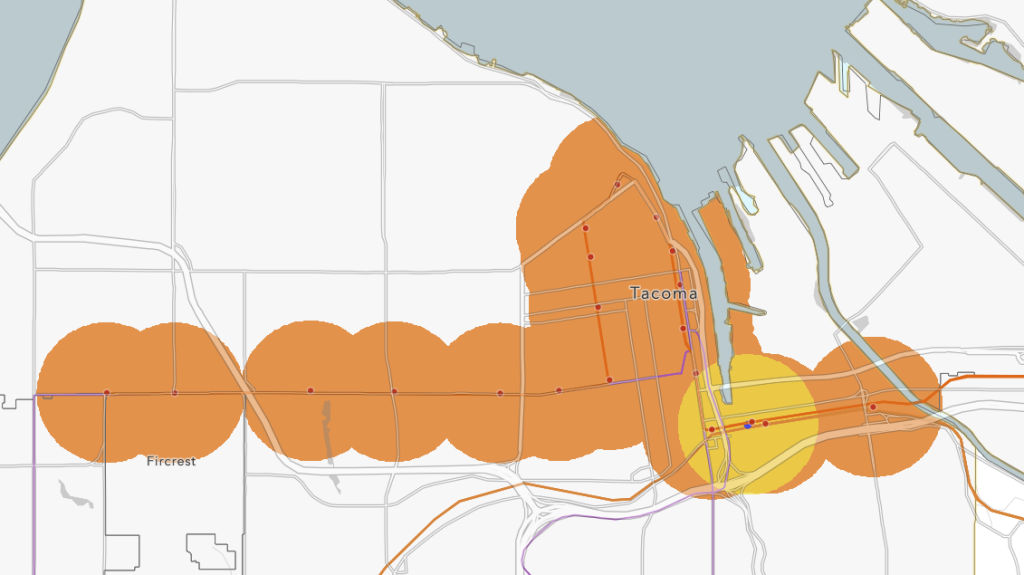

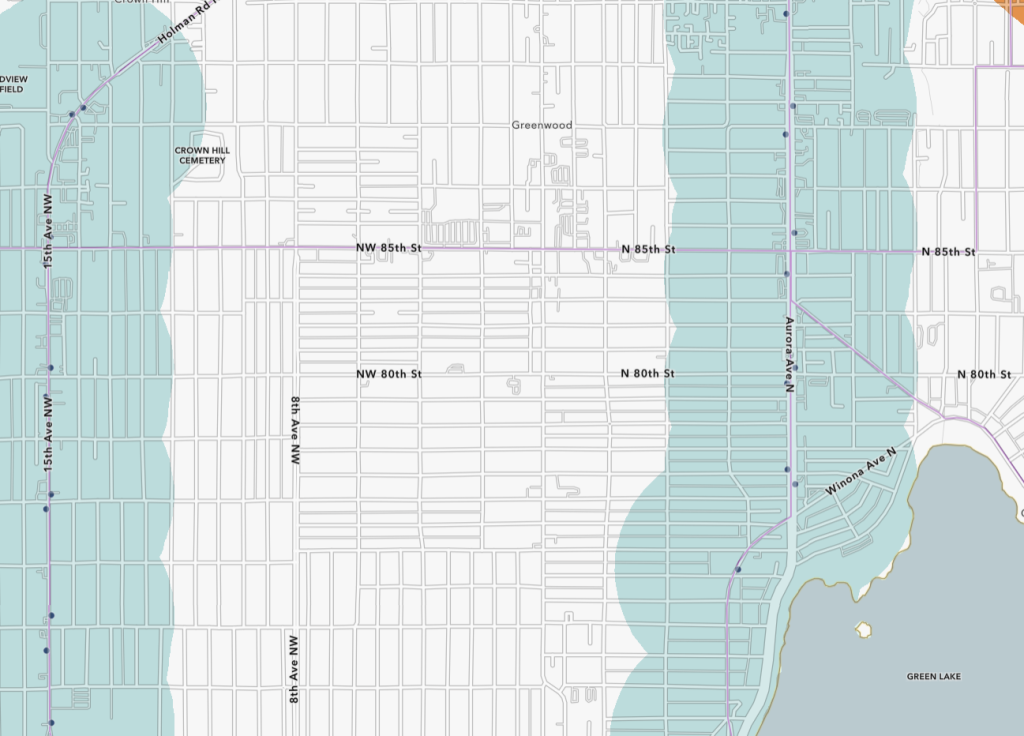

Senate Bill 5466, which passed off the Senate floor 40-8 last March, was a more expansive bill, allowing larger buildings, and it also included more transit stops, applying within a half-mile radius of any bus that comes at least every 20 minutes for most of the day. A map showing where it would apply, produced by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) and released after it passed the Senate, illustrated just how much of Seattle’s metro area would be impacted by the bill, clearly raised concerns among lawmakers that it was too expansive. The Association of Washington Cities raised the alarm about its “broad scope” and the toothpaste was likely out of the tube for good.

But the biggest difference between last year’s Senate bill and this year’s House bill is an affordability mandate: even if not taking advantage of the affordability bonus provisions in HB 2160, any new development that occurs within the station areas covered by the bill has to set aside 10% of the units for households making 60% of an area’s median income, and maintain those units as affordable for 50 years.

The affordability mandate, which tries to mirror and augment policies already in place in cities like Seattle, with the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, is an attempt to “capture” the value added by the additional development capacity. If cities already have denser zoning in place than what the bill allows, it wouldn’t apply, and existing affordability programs like MHA would be allowed to stay in place along with this mandate.

But the affordability mandate has been the part of the bill that many advocates for urban infill housing have raised concerns about, voicing worries that it will curb homebuildling and lead to underdevelopment in the exact areas of the state where so many benefits are gained by seeing incredibly dense development.

Representative Julia Reed (D-36, Seattle) is one of the main architects of this HB 2160, and is its prime sponsor in the House. It fell to Reed to find a consensus on the House side last year when it became clear that the bill passed by the Senate didn’t have enough support in the Democratic caucus to pass. Reed defended the affordability mandate as an essential element in the bill.

“There’s just no support in the House or the Senate, for sweeping zoning changes like this that do not include some aspect of mandatory affordability,” Reed told The Urbanist early this month. “I think that there isn’t a world in which we do this without affordability, so if that’s going to be an issue, how else can we come to a compromise?”

Reed pointed to cities like Shoreline that are seeing significant housing growth with an affordability mandate in place. Shoreline requires developers to set aside 10% to 20% of the units in multifamily buildings immediately around coming light rail stations to lower-income residents. But it also allows them to participate in the Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, receiving a tax benefit from setting aside those units and recouping some of the cost of the mandate. That’s somewhat similar to the direction that the City of Portland has been moving when it comes to affordability mandates.

“I’m not anti-developer, I get that we need market-rate housing, we need developers to do their part,” Reed said. “And developers are going to do what they need to do in order to make projects pencil out for them, and I respect that. But I think that the way that we set this up allows for plenty of folks to get what they need to get out of projects to make the projects pencil, and allows us to capture a small amount of reasonable public value.”

When would it take effect?

The short answer to when HB 2160 would fully take effect is the end of 2029. That’s much later than it would have been required to be implemented had a bill made it through the legislature last year, due to the schedule of when Washington cities must complete a periodic update to their comprehensive plans under the state’s Growth Management Act. To decrease the administrative burden on cities, the TOD bill piggybacks on those local comprehensive plan updates.

With all cities in Central Puget Sound’s most transit-rich areas required to get those updates done by the end of this year, local planning departments are already grappling with significant changes to their land use codes that need to be adopted soon, including last year’s middle housing bill, and a sweeping overhaul to accessory dwelling unit regulations. So the legislature is giving the cities in those counties more time to implement HB 2160, with the deadline extended to when completion of their mid-cycle implementation progress report is due — five years after this update.

“It was tough to say we’re going to wait for the bigger cities until the five year comp plan update,” Reed said. “I’m hopeful that many of these larger cities will do their updating sooner, just knowing that this is coming… there’s no reason to delay.”

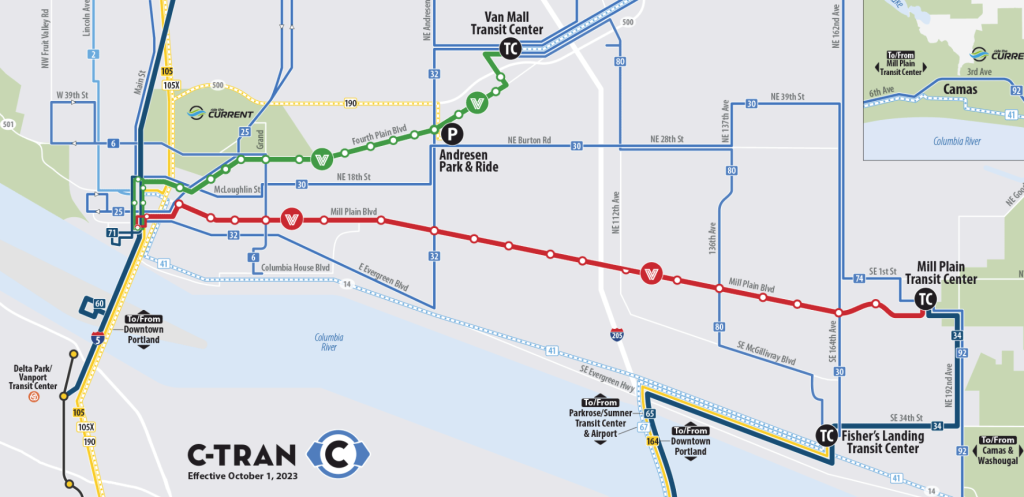

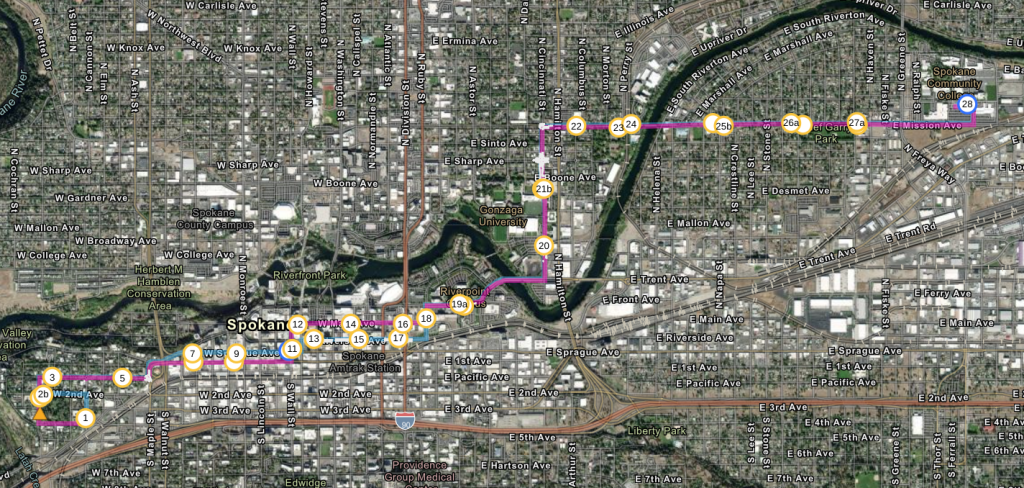

With only a few other counties in the state with current or planned light rail and BRT systems, just two cities outside Central Puget Sound will be impacted by the bill: Vancouver and Spokane. Vancouver, with its two Vine BRT lines currently operating and a third on the way, will end up being first, with the exact date of its implementation deadline still up in the air as the legislature considers a different pair of bills that would move their comprehensive plan update schedule, but it’s set to be within six months of mid-2026.

Spokane, which saw the launch of the City Line last year and which also has a BRT line in development along N Division Street, would follow Vancouver, with an implementation deadline at the end of 2026. Among Washington’s large cities, Spokane has been a leader in terms of rethinking its old land use patterns, taking steps to add density throughout the city.

Outside Vancouver and Spokane, cities like Mercer Island who are opposed to the rezones that HB 2160 would bring would ultimately have until the end of 2029 to comply with its parameters. There is an alternative pathway that cities can take, however, to avoid having the legislature fully dictate zoning in their station areas. If a city rezones the areas in question by next June, in a way that the state Department of Commerce finds is “substantially similar” to what HB 2160 requires, with one of the requirements being that no parcels within the station area remain zones for single-family detached residences, they’re considered in compliance with HB 2160. That provision could give forward-thinking jurisdictions an incentive to go even further than the bill requires them to.

The Puget Sound Regional Council has created a map showing most areas where the bill would apply in Central Puget Sound, though the map doesn’t include 100% of the stops that would be covered under the bill — RapidRide J Line, for example, along Eastlake Avenue E in Seattle is not included. But it does provide a fairly clear idea of the bill’s total impact.

What would be required around rail stops?

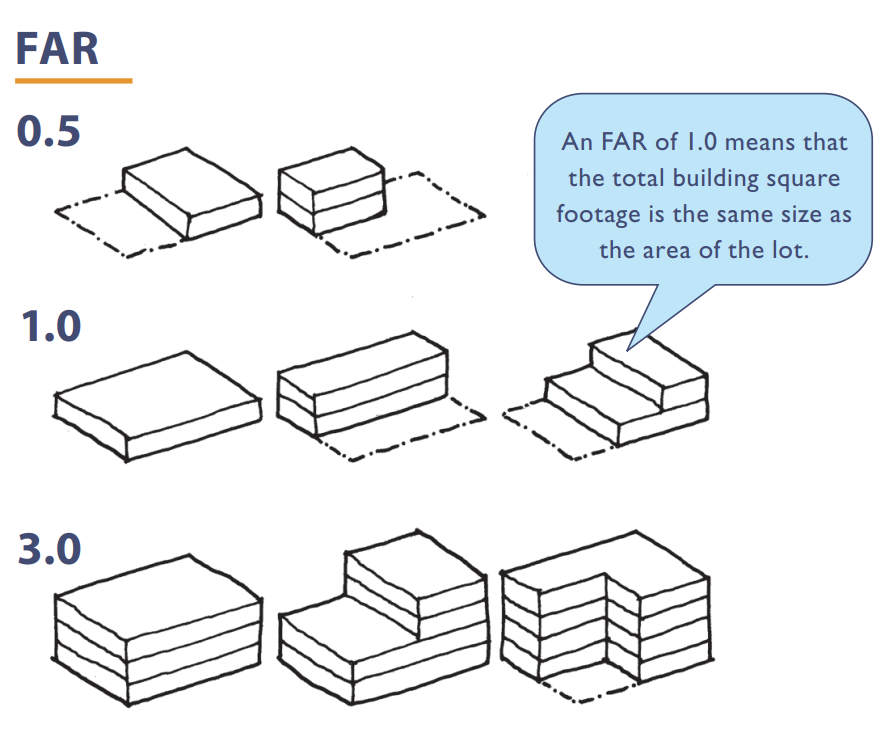

So what would HB 2160 actually require? The bill uses a wonky term buried in many cities’ land use codes to frame what would now be allowed around major transit stops: floor area ratio (FAR). Floor area ratio is essentially how much usable floor space a building is taking up on a lot. The higher the allowed FAR, the larger a building can be. A one-story building taking up the entirety of a lot has a FAR of 1.0, and a four-story building taking up exactly half of a lot has a FAR of 2.0.

Around rail stops, including light rail, streetcar, and Sounder commuter rail, the bill requires cities to allow an average of 3.5 FAR. Since they have a half-mile area to play with, local governments could decide to go higher immediately around the station itself, allowing less additional capacity further out, but it would have to average out to 3.5 FAR throughout.

Developments in which 100% of the units are going to be dedicated as affordable for that 50-year timeframe can receive an additional 1.5 FAR bonus, bringing the total to 5.0. And any three-bedroom units constructed as part of a development are exempt from FAR, theoretically encouraging the addition of units that can accommodate larger families.

But some housing advocates are concerned that the baseline density being set at 3.5 FAR isn’t going to be enough. One of them is Dan Bertolet, senior researcher at the Sightline Institute.

“Sightline is a huge proponent of legalizing homes near transit, but we think this bill still needs work,” Bertolet said last week to the Senate’s local government, land use, and tribal relations committee. “First problem is, it doesn’t legalize the level of housing density that’s appropriate for the state’s biggest transit investments. Near light rail stations in places like Redmond and Shoreline, we’re typically seeing six-story apartments get built, but the bill’s allowance for 3.5 FAR isn’t enough for buildings of that size.”

Moreover, Sightline and other market-oriented groups object to the blunt affordability mandate.

“The second problem is the bill’s one-size-fits-all affordability requirement could end up doing more harm than good,” Bertolet said. “It’s widely accepted best practice to calibrate affordability requirements to local market conditions, to avoid making it financially infeasible to build any housing.”

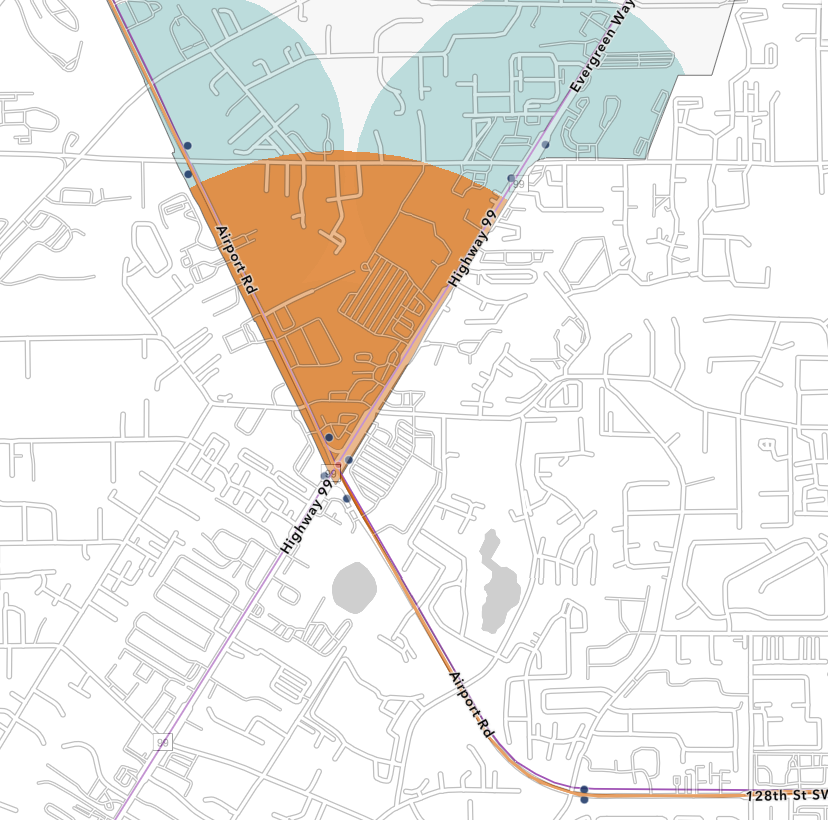

It’s important to note that the bill doesn’t apply to counties, and there is no requirement for unincorporated county land to be rezoned. That leads to odd situations where if Sound Transit’s planned Everett Link station at SR 99 and Airport Road, currently an unfunded provisional station, moves forward, only the area around the station within the City of Everett would require rezoning. Of course, Snohomish County could opt to voluntarily rezone the area.

What would be required around “bus rapid transit”?

Within a quarter-mile radius of bus stops on lines meeting the state’s definition of “bus rapid transit,” such as King County Metro’s RapidRide or Community Transit’s Swift Lines, cities could cap building density no lower than 2.5 FAR. This is true even for Sound Transit’s premier planned BRT lines, the Stride series, with a current project budget of $2.7 billion dollars and a system intended to function just like light rail.

As with rail stops, cities just need to allow 2.5 as the average FAR, but with a smaller footprint to work with and more station areas, creating more granular zoning within every individual stop’s radius will be a lot trickier. Ironically, the more stops a BRT line has, the more it ends up functioning like a local bus, a transit type not covered in the bill. And yet more stations means more development capacity.

With 2.5 FAR, BRT stations would see less additional development capacity than rail stations, but under the maximum uses, areas could see smaller apartment buildings. But development pressures could also create incentives that push developers toward more townhouse-style developments around these bus stops, potentially limiting their full potential.

Futurewise is one organization that is fully supporting HB 2160. Last week, they released a study showing a “significant potential increase in development for most areas” where the bill would apply, with 68% of the gains seen around rail stations, according to their parcel-level analysis. In total, Futurewise’s analysis suggests that the bill could open up an additional 3.6 billion square feet of development capacity.

“While this study indicates a substantial potential for new development capacity, it’s important to consider these figures as estimates due to data and methodological limitations,” its conclusion states. “Future refinements in data and methodology could enhance certainty about the bill’s capacity impact. Despite these limitations, this study findings strongly suggest that this bill could have a significant impact on housing production, public transit access, and urban development in the central Puget Sound region.”

“Futurewise is thrilled to see HB 2160 pass out of the House,” Alex Brennan, Futurewise’s Executive Director, told The Urbanist. “This bill is a crucial part of solving our housing and climate crises by connecting more Washington families to jobs and services via transit. We look forward to collaborating with our allies in the state Senate to pass this legislation in 2024.”

Onto the Senate

HB 2160 passed the House on February 13 almost exactly along party lines, with no Republican votes in support and Rep. Mike Chapman (D-24, Port Angeles) the only Democrat to vote against. That lack of bipartisan support could spell trouble for the bill, with only a small number of Democrats needed to pull support for the bill to ensure that it doesn’t make it across the finish line.

Its first hurdle, however, will be the Senate’s local government, land use, and tribal relations committee, a small committee with just three Democrats and two Republicans. Chaired by Senator Liz Lovelett (D-40, Anacortes), it’s that committee that decided not to give a hearing to HB 1245, a bill making it much easier to split residential lots across the state, after it passed the House on a 94-4 vote on the first day of the session.

Ultimately, even if the bill is not able to make it out of the Senate, the form that the bill is in now provides a significant insight into how the Washington State House of Representatives views land use and transportation policy, and how future fights over boosting housing production via state preemption of local jurisdictions will go.

“I think this bill does not have absolutely everything that I would wish [for] in a TOD bill. […] I’ve been pretty vocal that I would love to do all frequent bus service so that this is in more communities, and you know, there’s other things I would change,” Rep. Reed said. “But I think, it’s a very good compromise bill that does what I want, which is increase density around transit stops — around our most expensive, most used transit investments — and also ensures that the communities that are going to be built around these investments are mixed-income, mixed-use communities, that have a really good chance of creating kind of vibrant, places where lots of people can belong.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.