To many, Bellevue is seen as a polished edge city with a car-friendly downtown surrounded for miles by quiet neighborhoods of well-to-do mid-century single-family homes. But last week, the city put out its preferred growth strategy for the next 20 years that could dramatically alter that perception, at least in part. That strategy would provide capacity for an extra 152,000 homes and 185,000 jobs, for a grand total of 216,000 homes and 323,000 jobs when accounting for existing capacity.

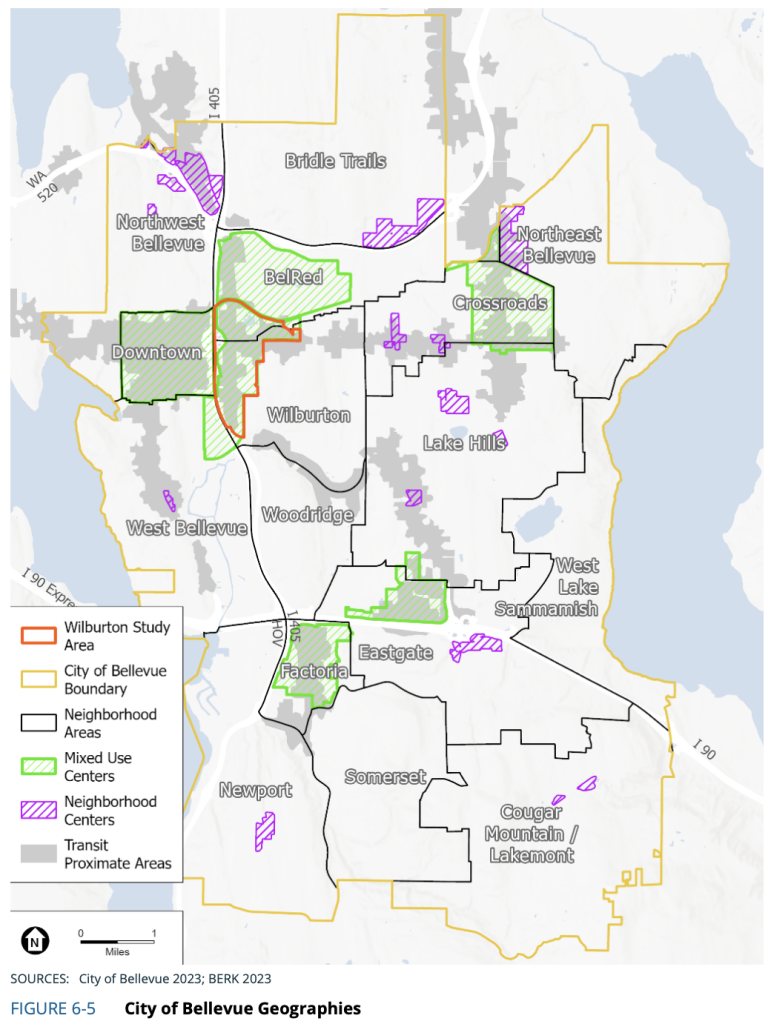

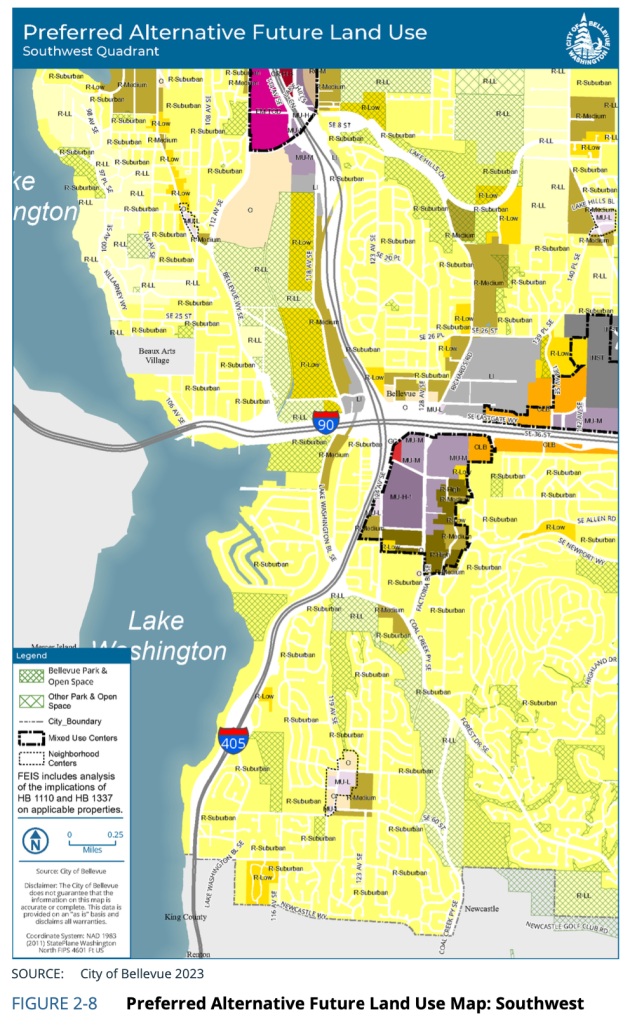

Bellevue’s growth strategy would seek to expand the urban core east of I-405 into Wilburton and the medical district, largely following the path of light rail, which is set to commence service this spring with the Eastside Starter Line. Other existing commercial and multifamily nodes dotting the city could also see substantial zoning changes allowing for more housing and commercial activity. Layered on top of this, Bellevue would meet state mandates to allow middle housing and accessory dwelling units broadly in the city, including in the city’s expansive single-family residential zones.

Bellevue could become a metropolis in its own right

It’s this multi-pronged strategy that could see the city, in time, bring in another 351,000 residents. That’s quite a change for a city that was only allocated 35,000 new homes between 2019 and 2044 under countywide growth target allocations in 2021, translating to about 86,800 new residents.

Bellevue’s currently home to about 154,600 residents, according to state estimates, which suggests that if the city were completely built out under the preferred growth strategy, Bellevue might top 500,000 residents. That, however, is an unlikely scenario in the 20-year planning time horizon for several reasons.

In a modeled analysis, Bellevue expects that housing growth would reach a more modest 33,000 net new units. That’s 2,000 fewer units than the city’s growth targets, and 118,600 fewer homes than total capacity under the preferred growth strategy. Consequently, Bellevue would add around 81,840 residents under this likelier scenario — a 65% increase from today but a little less than half of what zoned capacity would allow for.

On top of that, it’s one thing to develop a comprehensive plan with ambitious housing goals and quite another thing to deliver on it. Bellevue’s historic growth rates couldn’t demonstrate that more clearly.

During a mid-cycle review of growth, King County found that Bellevue was struggling to reach the housing production pace needed for the city to reach its 2035 growth targets. Data released in 2021 with a 2006-2018 look-back period indicated that Bellevue was only reaching 79% of its 2035 housing target and had only produced 6,591 net new housing units. Conversely, Seattle had produced nearly 10 times the number of net new housing units during the same period and was already on pace to reach 154% of its 2035 housing target.

Bellevue has seen a tremendous housing boom in its downtown and the Spring District in recent years though. Over 11,000 homes are in the development pipeline (i.e., permitting or construction), mostly in those two parts of the city.

In order for Bellevue to reach its modeled 2044 housing capacity under the preferred growth strategy, the city would need to build over 1,650 new homes per year and have thousands more homes in the permitting pipeline at any given time. Accomplishing that is not exactly a science though, requiring the right balance of regulations, process, and tax incentives along with a favorable economy and construction costs to encourage builders to build. Some of that is obviously in the city’s control and would require intentional implementation of the growth strategy.

Significant growth would be directed into existing commercial and multifamily areas

While the preferred growth strategy would significantly increase development capacity across the city, it essentially leaves in place the existing hard boundaries between suburban residential areas and urban mixed-use, commercial, and multifamily areas.

The consequence of this is that some areas immediately within light rail and bus rapid transit walksheds wouldn’t become conventionally transit-oriented districts with a mix of uses and high densities. Areas west of South Bellevue Station and west of the East Main Station are two examples for light rail where suburban residential land uses are proposed to be retained. The same is true for many portions of the RapidRide B Line’s corridor on NE 8th Street. Nevertheless, state middle housing requirements could still impact areas closest to light rail and bus rapid transit stops with allowances for up to six dwelling units per lot.

To maintain existing hard boundaries, the preferred growth strategy would essentially put its mandatory growth from the county into existing mixed-use, commercial, and multifamily areas. These areas would see numerous land use changes with many commercial and multifamily areas becoming mixed-use areas or seeing their development capacity limits (e.g., height limits, floor area ratio, and unit density limits) increase.

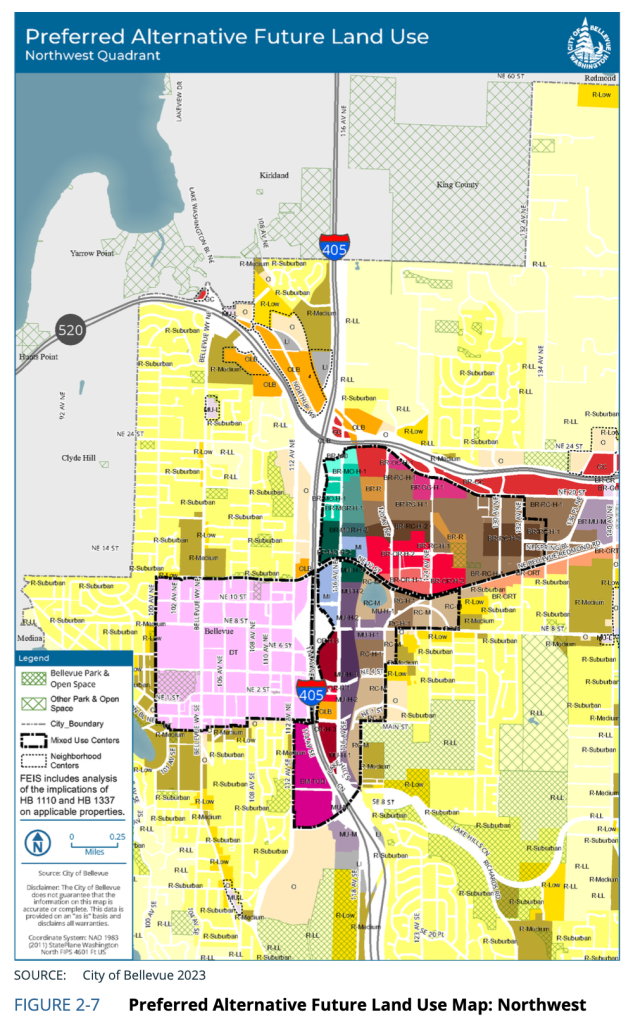

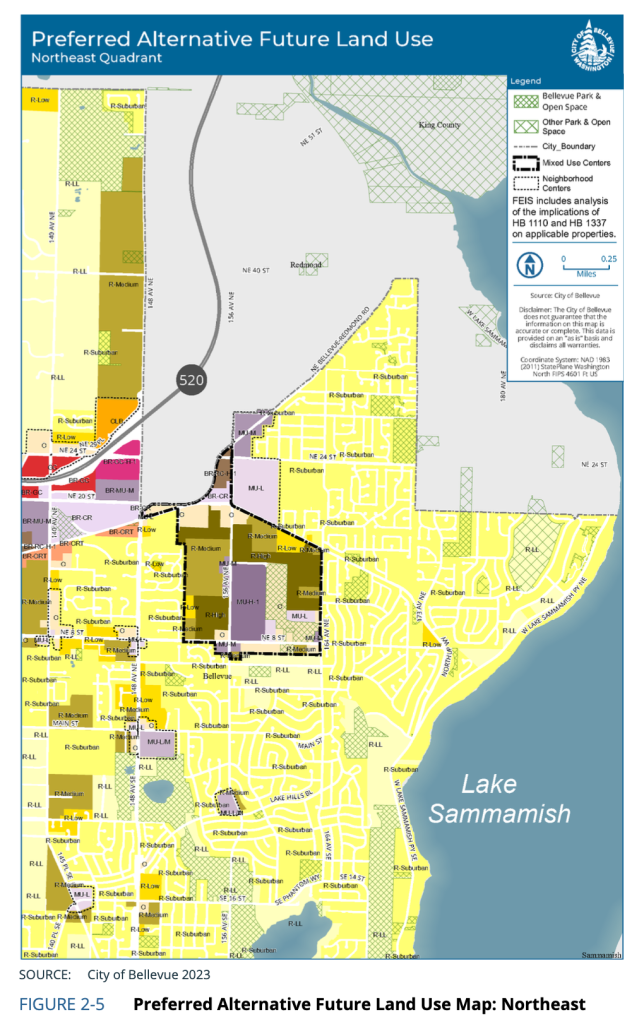

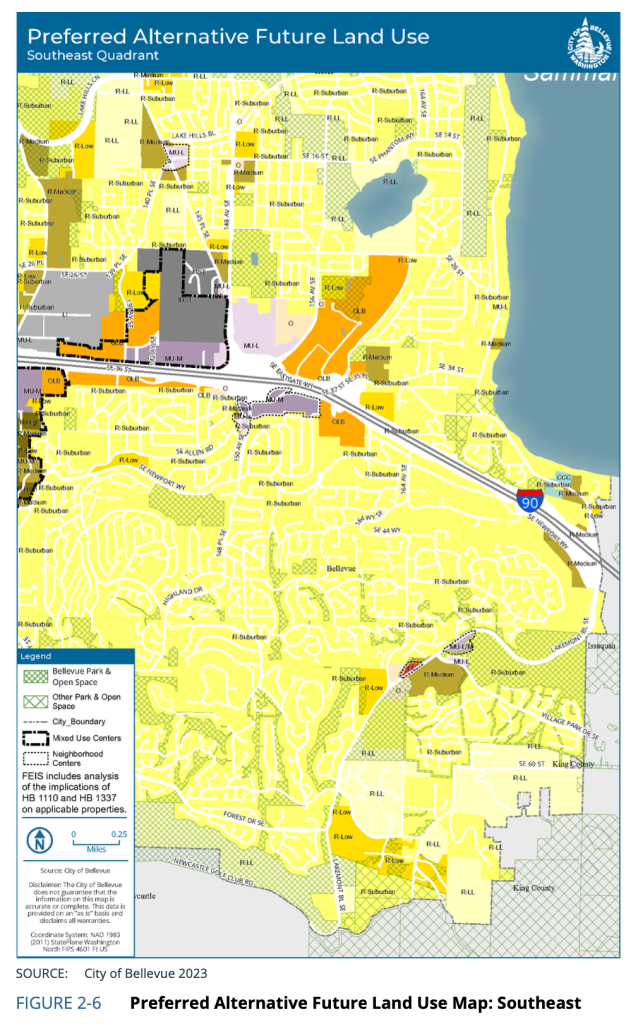

For instance, new residential highrises would be directed into Crossroads and Factoria — both potentially allowing buildings up to 16 stories on some parcels — and Wilburton with mixed-use buildings up to 45 stories between I-405 and the Eastrail corridor under proposed future land use maps (FLUMs). In Factoria, the FLUM would also change to broadly allow mixed-use development for seven- to 10-story midrise buildings.

| Geography | Net New Housing Units | Net New Jobs | Net New Commercial Square Footage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Use Centers | 64,600 | 168,900 | 54,700,000 |

| Wilburton Area | 14,800 | 35,500 | 12,000,000 |

| Transit Proximate Areas | 42,400 | 113,500 | 38,900,000 |

| Neighborhood Centers | 3,100 | 2,900 | 1,100,000 |

| Low Density Residential Areas | 72,200 | -200 | N/A |

| Citywide | 152,000 | 185,000 | 60,300,000 |

| Mixed Use Center | Net New Housing Units | Net New Jobs |

|---|---|---|

| Downtown | 19,500 | 58,000 |

| Wilburton-East Main | 17,000 | 46,200 |

| BelRed | 16,700 | 36,100 |

| Crossroads | 6,400 | 15,100 |

| Factoria | 4,200 | 11,500 |

| Eastgate | 800 | 1,300 |

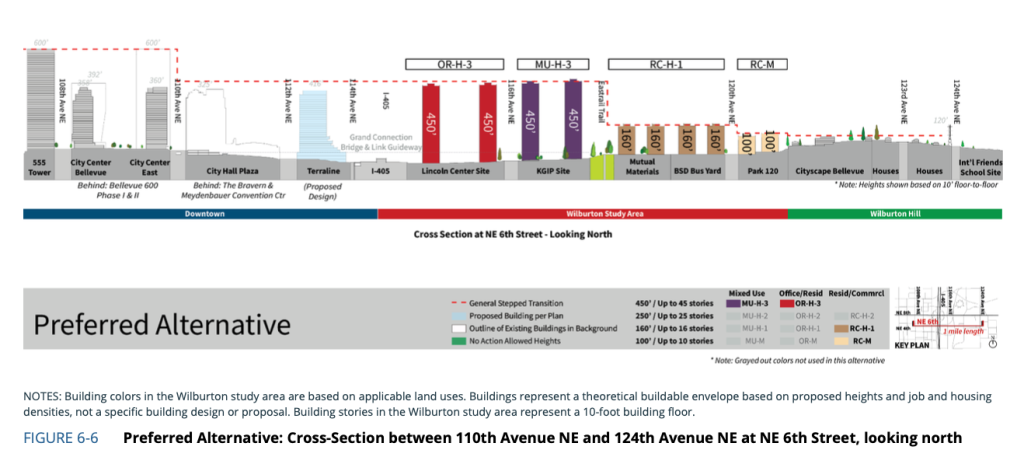

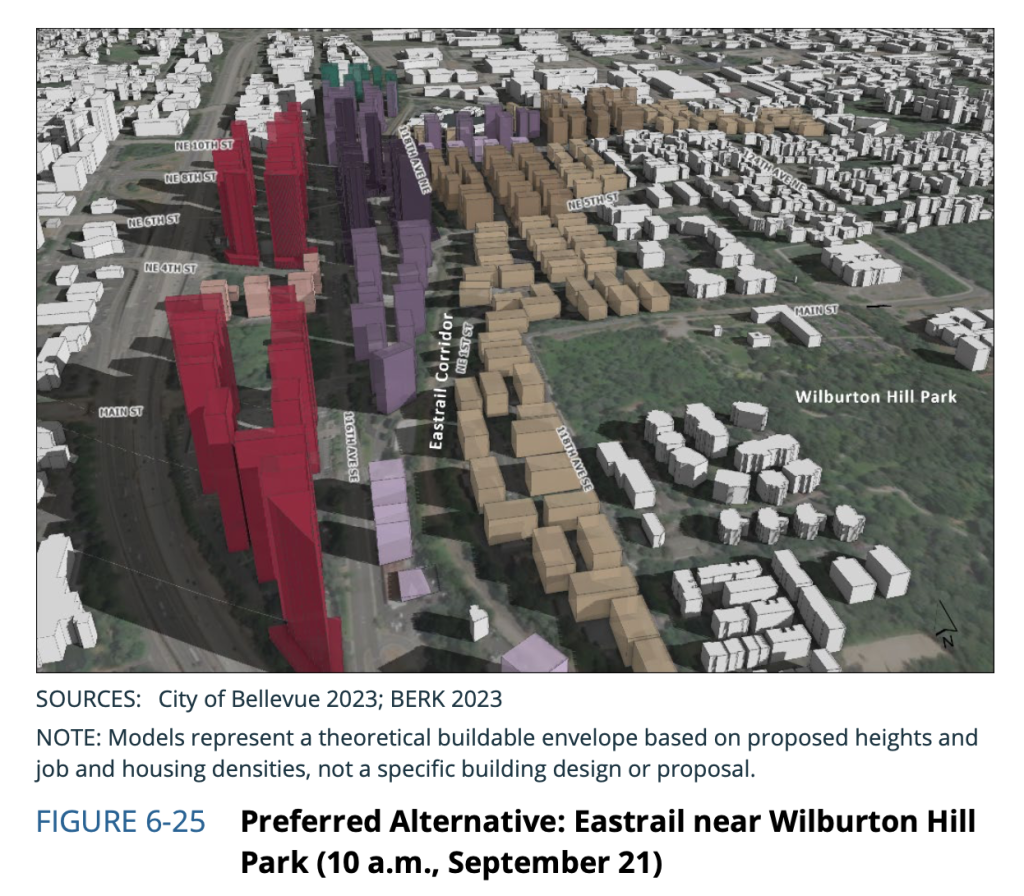

In Wilburton, the growth strategy would pursue 25-plus-story medical buildings near NE 12th Street and 116th Avenue NE and shorter residential and mixed-use towers north, south, and east of the core (between NE 8th Street and NE 4th Street). Embedded in the growth strategy is an east-west section drawing that shows the proposed height gradient from Downtown Bellevue to Wilburton Hill as well as a modeled build-out scenario. Both offer a window onto how development could eventually unfold east of I-405 with zoning changes in Wilburton.

Interestingly, proposed policies would also encourage Wilburton to focus development — particularly retail — around the planned Grand Connection bridge and lid over I-405 and future Eastrail. That’s in keeping with ideas that have come out of planning processes for both trail projects, though Bellevue is especially bullish on the Eastrail being expanded as not just a multi-use trail but also a wider linear park.

Beyond Wilburton, the preferred growth strategy would also allow more highrises near the Spring District, BelRed, and Wilburton stations serving the BelRed and medical districts with wedding cake zoning stepping down from around 25 stories to 16 stories and then to midrise and lowrise heights.

Missing middle housing could become common

Built into the preferred growth strategy is compliance with state mandates for middle housing and accessory dwelling units as prescribed by House Bills 1110 and 1337. In short, Bellevue is required to allow:

- At least six dwelling units on all lots predominately zoned for residential use within a quarter-mile walking distance of light rail stations and bus rapid transit stops;

- At least six dwelling units on all lots predominately zoned for residential use if two of the units are affordable;

- At least four dwelling units on all lots predominately zoned for residential use; and

- At least two accessory dwelling units on all lots that in zones that allow single-family homes.

These mandatory zoning changes, which are primarily in low-density areas of Bellevue, are significant in the growth strategy, representing about 48% of the additional development capacity. Areas of the city that were mostly hands-off from development could incrementally see development of missing middle housing, such as triplexes and sixplexes — if pre-existing covenants don’t stand in the way.

Lower-income housing would be a big need

Bellevue’s Housing Needs Assessment shows that the city has a significant deficit in affordable housing for households at 50% or below of area median income (AMI). Estimated need and capacity in the growth strategy shows that the city would need 18,195 homes at or below 30% of AMI, with 6,270 as permanent supportive housing units. Another 8,780 homes would be needed between 30% and 50% of AMI, plus 2,671 more homes between 50% and 80% AMI. Fortunately, the preferred growth strategy would have extra development capacity for these housing categories with a surplus for 10,361 homes in these categories.

Local programs like zoning density bonuses and parking exemptions, sales and real estate excise taxes for housing, and property tax exemptions are expected to stay on the books to facilitate affordable housing development, but the growth strategy has evaluated implementation of mandatory inclusionary housing programs into zoning. The state provided a partial nudge in this direction with HB 1110, which will require contributions in some cases.

The growth strategy is not yet set in stone

Ultimately, Bellevue’s preferred growth strategy is quite an evolution in the way that land use could unfold in the city. Going from a sprawling mid-century, post-war suburb with one or two areas of regional commerce and high-density development to a city with middle housing sprinkled throughout, numerous mixed-use centers, and an urban highrise core beginning to rival Downtown Seattle is no small thing.

But Bellevue’s path on land use is not settled until the city’s decision-makers — planning commissioners and the city councilmembers — have had their say. Final maps and zoning regulations will determine Bellevue’s future and those won’t be decided for many months yet. Residents can weigh in via the city’s engagement hub.

Correction: The forecasted housing growth and some related numbers in this piece have been updated to reflect assumptions in Appendix K of the FEIS, which assumes 33,000 net new homes by 2044.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.