Today, the Washington State House of Representatives passed House Bill 1932, which “aims to bolster local democracy, enhance voter turnout, and foster equitable representation across communities by granting jurisdictions the option to conduct elections in even-numbered years instead of odd-numbered years.” The vote was 52-45, primarily along party lines, with nearly all Republicans opposed.

The bill heads to the state senate where it will also need to secure passage to become law. The companion Senate Bill 5723, sponsored by Javier Valdez (D-46, Seattle), remains dormant. Representative Mia Gregerson (D-33, SeaTac) sponsored the house legislation — not for the first time after the effort came up short in previous years — and emphasized inclusivity in her statement.

“This is about addressing disparities in participation,” Rep. Gregerson said. “It’s about ensuring that elections reflect the broader population and foster inclusive governance.”

Support appears to be building for the reform in part because the turnout problem is getting worse.

The 2023 election set a new record low for voter turnout dating back to when Washington State started keeping track of turnout figures in 1936. In contrast, Washington State’s voter turnout surpassed 84% in the 2020 presidential election — 2.3 times higher than in 2023.

Election reform advocates including Northwest Progressive Institute (NPI), Sightline Institute, and Washington Community Alliance ramped up efforts to advance legislation this cycle.

“After last year’s worst-ever statewide general election turnout, in which only 36.41% of Washington voters returned ballots, we called on state lawmakers to work with us to liberate localities across our state from being locked into holding their regularly scheduled elections in low turnout, odd-numbered years,” NPI executive director Andrew Villeneuve said in a press release commending state representatives for passing the bill.

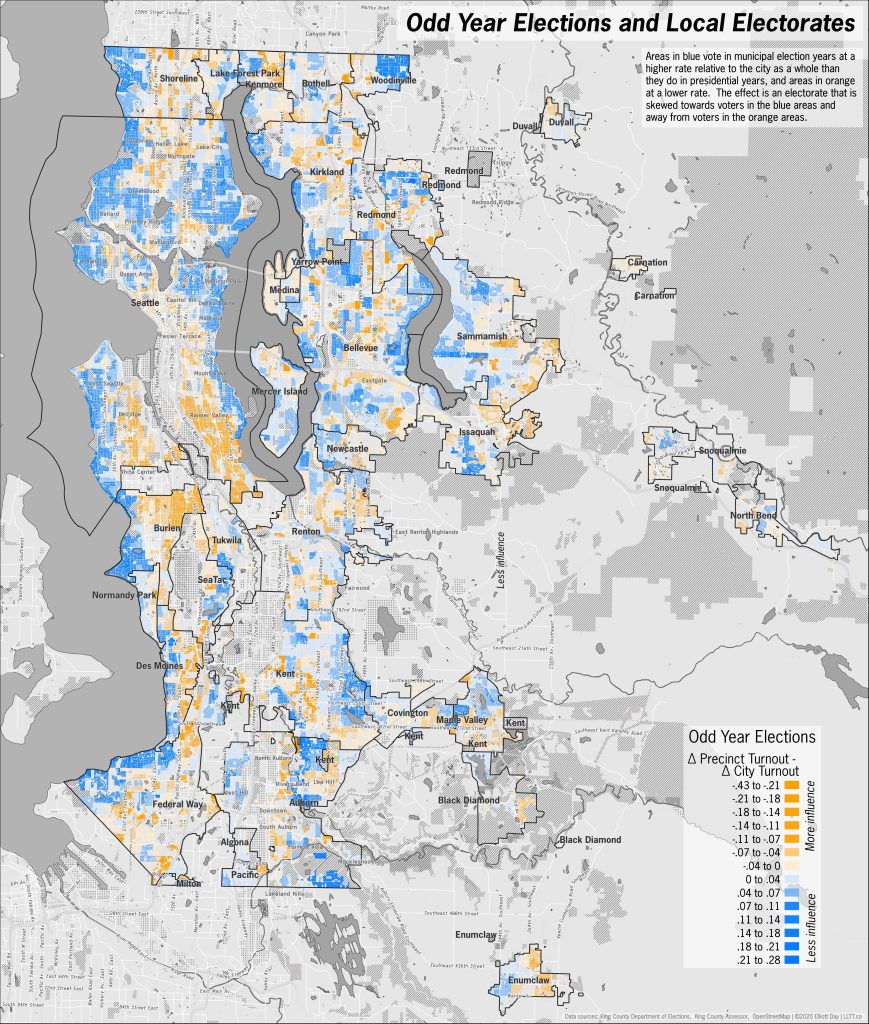

An increasingly small subset of Washingtonians are selecting influential city and county leaders and deciding odd-year ballot measures. Voter data shows that that odd-year voting subset tends to be wealthier, older, Whiter, and more likely to own their home than the population writ-large. This has big implications for policymaking, shrinking the voice of tenants and magnifying that of single-family homeowners, for example. Low turnout likely flipped at least one recent Seattle City Council race.

“Letting Washington cities hold their elections on the same ballot as national elections would put them in the same position is cities in nineteen other U.S. states: free to choose what’s best for them,” said Alan Durning, executive director of Sightline Institute. “Our research shows that on-cycle elections boost turnout dramatically, improve representation for working-age voters, and hold local leaders accountable to local values and preferences.”

House Bill 1932 does not require that local governments make the switch to even-year elections, but it does provide two different pathways to make the switch. Plan A is through a vote of the respective legislative body; Plan B is at the ballot, “via a democratic process where voters can approve relevant ordinances or charter amendments.” Bill backers note this ensures “active community participation” in shaping electoral practices.

This second pathway could prove important if the state does pass the bill, because several leading elected officials have already come out against making the switch to even-year elections.

Among them are state Secretary of State Steve Hobbs and Seattle City Council President Sara Nelson. With Nelson’s opposition, passing even-year election reform at the council level in Seattle appears fraught in the near-term, but a ballot initiative could circumvent opponents like her, who may be more comfortable with the status quo system that elected them.

“When you’re Sara Nelson and you got elected when half the electorate was looking the other way, you might be concerned under a system where more people know you’re on the ballot,” Kamau Chege, executive director of Washington Community Alliance, told The Stranger.

The case that Hobbs and Nelson make against the reform is similar. Both emphasize voter fatigue stemming from so many races — local, state, and federal — being on the ballot, pointing to participation drop off in down-ballot races. However, the data is clear that even with some down-ballot drop off in even years, turnout still vastly outnumbers odd-year elections.

Critics like Nelson also fret that federal issues could overshadow local ones with everything condensed into even years.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean a better informed public when it comes to the issues that impact people’s lives directly, from public safety to potholes,” Nelson said at a January council meeting. “These are the issues that we here at the dais deal with, and I’m concerned that there will not be time or there will not be interest in hosting all the forums my colleagues attended last year. Media will not be interested in the lower down the ballot races because of the high profile stuff like president and Congress. Down ballot participation hasn’t really been examined and for those reasons, I’m concerned about moving local elections to even years. I think that would be bad for cities across the state.”

However, some even-year supporters, such as Northwest Progressive Institute, argue that voter fatigue effect is stronger from having too many elections rather than putting too much on one particular ballot. Statistically, most voters do not return a ballot in off-year elections; most are not taking the opportunity to do extra homework with the extra elections they are given.

Moreover, advocates see taking a proven step to drive up voter participation rates as a civil rights issue. In his comments to The Stranger, Durning pointed to the history of racist Jim Crow laws, when many states forced Black would-be voters to pass “literacy” tests to prove they were worthy of participating in democracy.

“This country has a sad history of questioning voters’ knowledge,” Durning told The Stranger.

Voters themselves, when consulted on the matter, appear to strongly favor even-year elections. Led by County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, King County, which still had the freedom to move its election timing unlike municipalities, put even-year election reform on the ballot in 2022, and voters passed it resoundingly.

“This is something that voters really, really want,” Villeneuve said. “NPI’s previous statewide research has found that a majority of voters favor even year elections for localities, while only around a quarter are opposed. And when King County voters got the opportunity to consider our charter amendment two years ago to move twelve county positions to even years, more than 69% of them voted yes, mirroring the enthusiasm for this idea that we’ve seen around the country.”

Gregorson’s office noted that “local jurisdictions that elect to switch to even-numbered year elections would need to provide a transparent process, requiring two public hearings with a 30-day gap before adoption. Acknowledging the need for a seamless transition, the bill reduces the term lengths of officers elected in the next odd-year election if a jurisdiction opts for even-year elections. This pragmatic approach minimizes disruptions and ensures continuity in the electoral cycle.”

While the house vote mostly fell along party lines, Representatives Kristine Reeves (D-30, Federal Way), Melanie Morgan (D-29, Spanaway), Mari Leavitt (D-28, University Place), Dan Bronoske (D-28, Lakewood), Mike Chapman (D-24, Port Angeles), and Shelley Kloba (D-1, Kirkland) did cross the aisle to vote no with the Republican caucus. On the flip side, Rep. Greg Cheney (R-18, Battle Ground) voted yes, bucking the rest of the Republican caucus. As a smaller body, the senate will be able to survive fewer Democratic defections — at least without any offsetting Republican votes like Cheney.

The next step for even-year election reform supporters is to secure sufficient votes in the senate. To signal support, folks can sign in as pro to Senate Bill 5723 and contact their senators.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.