2023 saw traffic deaths and injuries skyrocket in Kent. The City has small safety improvements in the pipeline, but systemic changes may prove more elusive.

On January 21, 2023, Khalilov Akhmadzhon was walking along Kent-Kangley Road in Kent’s East Hill neighborhood when he decided to cross the street. Kent-Kangley Road has a 45 mph speed limit, and no marked crosswalks between 132nd Avenue SE, where a number of businesses are located including a Safeway, and 124th Avenue SE, a distance of nearly a mile. The roadway is five lanes wide.

That decision to cross the street at that moment cost Akhmadzhon cost him his life on that winter evening, after a driver struck him in the 12900 block of Kent-Kangley, 0.2 miles from the crosswalk, according to the Kent Police Department. He was transported to Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, where he died of his injuries. He was 70 years old. Before he passed away, the Kent Police Department was planning to issue him a citation for making an illegal crossing.

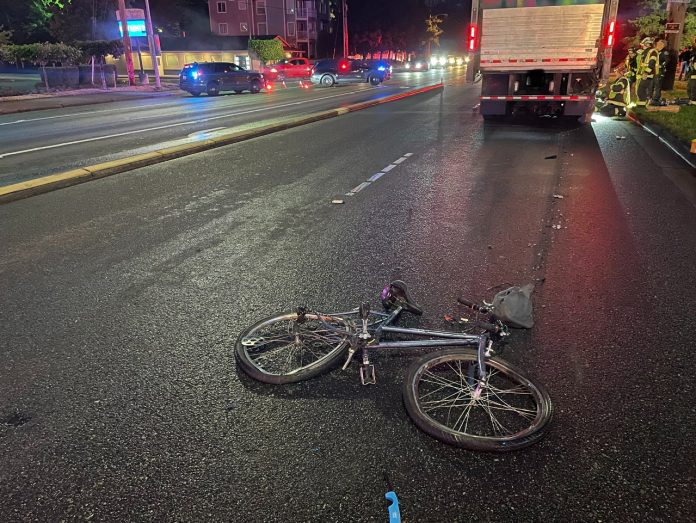

A little over six months later, on August 30, 2023, Carlos Gutierrez-Tinsley was killed riding his bike just a few blocks away from where Khalilov Akhmadzhon died, at Kent-Kangley Road and 132nd Avenue SE. Witnesses described seeing Gutierrez-Tinsley make an abrupt left turn into the path of an oncoming box truck driver. His mistake also cost him his life. The intersection he was using had no dedicated space for people on bikes.

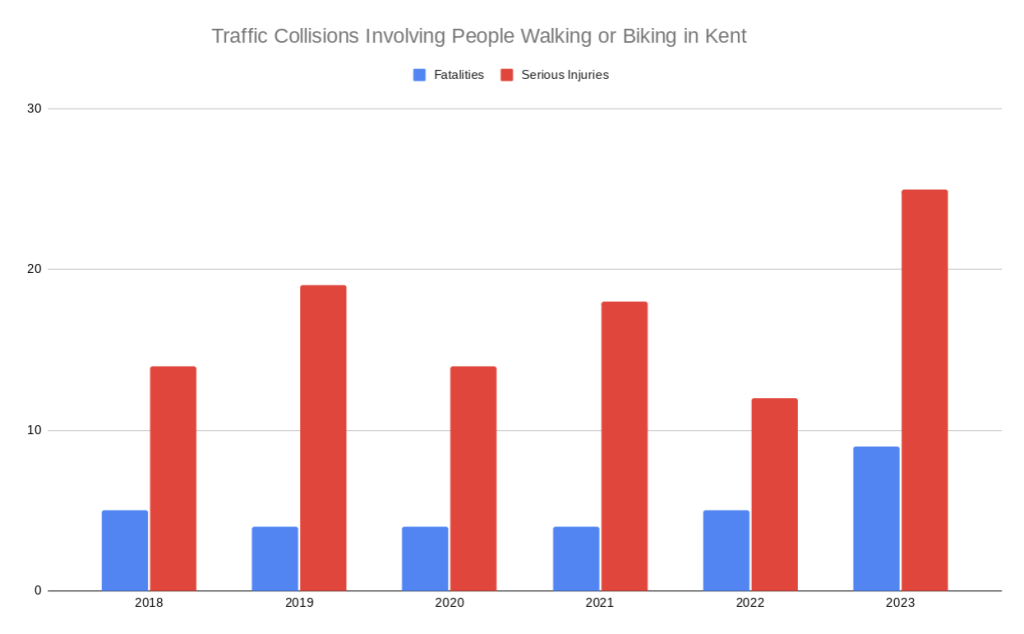

Akhmadzhon and Gutierrez-Tinsley were two of nine people killed while walking or biking around Kent last year, a city of 139,000 people. At least another 25 people were seriously injured while walking or biking during the same timeframe, according to preliminary data available from Washington State Patrol. All told, that is a 71.7% increase compared to the average of the previous four years.

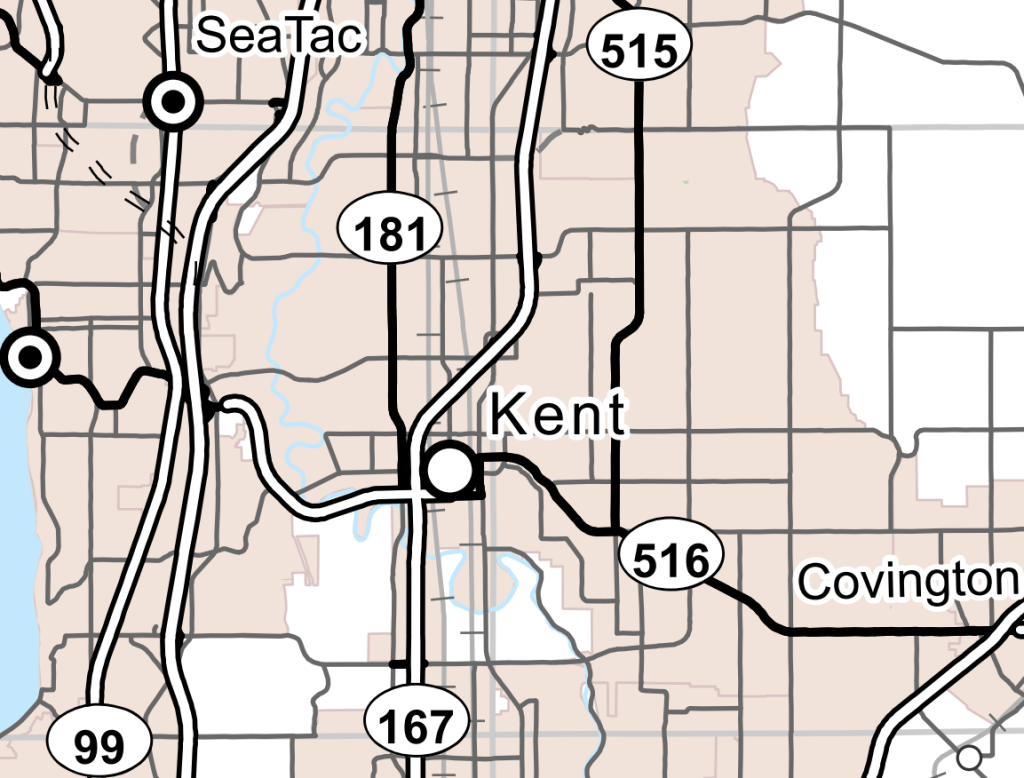

The City of Kent has a lot of roads like Kent-Kangley, which also functions as State Route 516. There’s 104th Avenue SE/108th Avenue SE through the East Hill neighborhood (SR 515), and the West Valley Highway through the heart of Kent’s industrial district (SR 181). And on the far west edge of the city is Pacific Highway S (SR 99), one of the most dangerous roads for people walking in the entire state.

Kent Mayor Dana Ralph sees the increase in traffic fatalities in her city as part of a larger trend that the City can’t tackle alone. “We are seeing increasing numbers across the region and the state. This is not a Kent-specific concern… so I think it would be unfair to characterize it that there’s something happening particularly in Kent,” Ralph told The Urbanist earlier this month.

But the data shows that many of Kent’s streets epitomize the conditions that are leading to spikes in serious traffic crashes across the state, particularly when it comes to people who are walking and biking, and whether a city like Kent will be able to make progress will determine whether Washington as a whole will be able to do the same.

In 2022, the city of Kent completed a road safety plan that looked at crash patterns across the city for a five year timeframe, 2016 to 2020. Out of all fatal and serious injury crashes that occurred in Kent over those five years, the single most common type of crash was someone walking being hit by a driver, with just under one out of every three crashes involving a pedestrian.

Of those 72 pedestrian crashes — approximately one per month — 88% occurred on streets with a posted speed limit of 35 mph or more, the exact same percentage that occurred on streets with five or more lanes. Nearly half (44%) occurred over 300 feet from the nearest marked crosswalks, and yet only 8% occurred over 600 feet away from a transit stop. The data paints a picture of high exposure to danger for pedestrians using Kent’s busy arterials. In only 10% of the crashes was the driver recorded as actually exceeding the posted speed limit.

The road safety plan that broke down that data follows on the heels of Kent updating its Transportation Master Plan in 2021, an event that City staff point to as a turning point.

“This plan was our first major step to move from a vehicle-centric transportation network to a multimodal network…our last update was in 2009, so things were pretty much vehicle-centric at that time,” Rob Brown, Kent’s Transportation Engineering Manager, told The Urbanist.

Next, with the help of a grant from United States Departments of Transportation, Kent is creating a Target Zero Action Plan. That’s a lot of work on plans, but are all intended to move the city toward a new approach to traffic safety, focused around creating Safe Systems.

John Milton is the Washington State Department of Transportation’s (WSDOT) state safety engineer and more than any transportation official has been leading the charge on the shift to safe systems.

“From the past way of looking at safety, it was often from a singular point of view, and that was from reducing the likelihood of a crash occurring,” Milton told The Urbanist. “When you think about it in terms of the Safe System, you’re focusing not just on that, but those high severity, high speed sorts of crashes, to bring down what is happening out on the road, and what’s leading to the injuries that are happening.”

Milton explained that simply reducing exposure is one of the most effective ways to improve safety. “Some of the things that you’d see with WSDOT or anybody who’s moving into the safe system, is a fundamental way of looking at separation between modes… in contexts where it’s necessary, and that would be where you see high speed locations.”

Separating users means more places to cross the street, and signals that separate people walking and biking from drivers in time, and more dedicated biking and walking facilities separating them from drivers in space. Maintaining an unmarked crosswalk across a five-lane state highway between a bus stop and a public library, as is the case with the King County Library System’s branch in Panther Lake, is an example of where Kent’s current non-motorized network encourages exposure to high risk.

Ralph touted speed limit reductions and the addition of mid-block crosswalks for pedestrians on some of the city’s megablocks. “We’re very fortunate that the Interurban Trail, the Green River [Trail], they ran right through the middle of town, which create great paths for cyclists to be very, very separated, we have been adding bike lanes all over the community for quite some time,” she said.

But apart from those two trails, the bike network in Kent remains very fragmented, and city staff confirmed there is no current project aimed at connecting the segments into a broader network.

“There is an urgent need for Kent to improve infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians,” Prem Subedi, a Kent resident, and a member of the Kent bicycle advisory board, told The Urbanist. “There are many improvements that the city has in the Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), but there are still gaps in it which prevent the usage and our city still uses the 85 percentile rule to determine the road speed.” Of the sparse network of paint bike lanes that currently exists in Kent: “It’s a bike lane in name only,” he said.

Subedi pointed to Sound Transit’s plans to add a new, $70 million parking garage in downtown Kent next to its Sounder commuter rail station, even though the city already provides a significant amount of free parking in downtown. A small amount of additional funds were provided by Sound Transit to pay for bike and pedestrian improvements around the station, but the amount was dwarfed by the amount allocated toward parking.

Improvements on the Horizon

In touting the shift toward a more multimodal approach to transportation, Kent city staff touted a number of projects either underway right now or about to start construction in the coming years. The list offers some hope that Kent is at least starting to move in the right direction, if not at the pace needed.

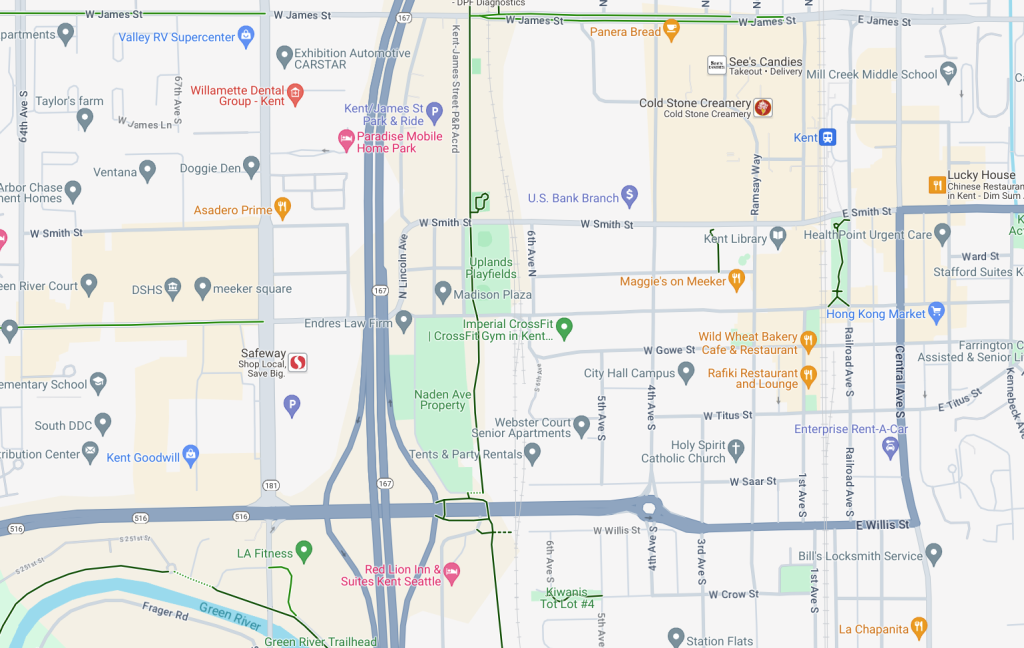

Kent’s flagship streetscape improvement project is “Meet Me on Meeker,” a plan to rechannelize developing Meeker Street between downtown Kent and Riverfront Park, reducing the number of travel lanes and making way for both a wider sidewalk with seating as well as a two-way cycle track that will ultimately connect the Interurban Trail with destinations elsewhere in the city.

The City has been completing Meet Me on Meeker in phases, and has been very competitive in winning federal and regional grants to help the effort. A substantive segment in the middle of the corridor has already been completed

The project does demonstrate that Kent as a whole gets how to remake its streets to make them more people-centric, but at several million dollars per segment, the project can’t really be scaled across the streets where pedestrians and cyclists are getting hurt and killed.

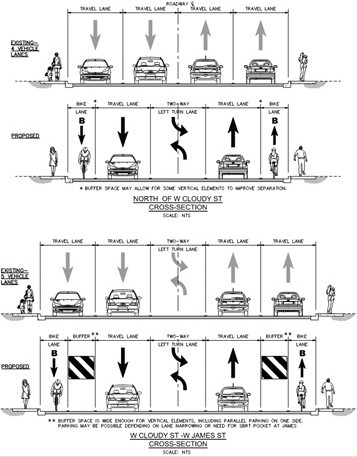

Kent is also moving to implement rechannelizations — which it’s calling “road diets” — on some of its other overbuilt arterial streets. S 260th Street and S 259th Place, underneath I-5 on Kent’s West Hill, has lanes so large that it won’t even take away any to create room for bike lanes. And 4th Avenue N, connecting underneath SR 167 north of downtown, will see two lanes in each direction modified into one with bike lanes and a central turn lane — copying a successful model for rechannelizations that has been implemented in Seattle for over a decade.

But an opportunity to think how one of Kent’s surface-running state highways function through the city could provide a chance to go further than many of these individual projects on city arterials propose to. Thanks to 2022’s Move Ahead Washington transportation package, any repaving project on a state highway triggers evaluation for filling in gaps in the walking and bike network, with statewide standards for separated bike facilities. The only thing holding this change back from potentially transforming streets like Kent-Kangley and Pacific Highway is the fact that the state legislature hasn’t actually backed up its promise with real maintenance dollars to jumpstart projects in cities across the state.

With cost overruns on highway expansion projects taking center stage right now over maintenance, it’s not clear if the legislature will ever get around to funding its maintenance backlog. But cities like Kent offer a clear illustration of where state investment would be able to do the most good. And where immediate action would be able to save lives.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.