Facing half-hour headways downtown through February 4, riders are complaining of overcrowding.

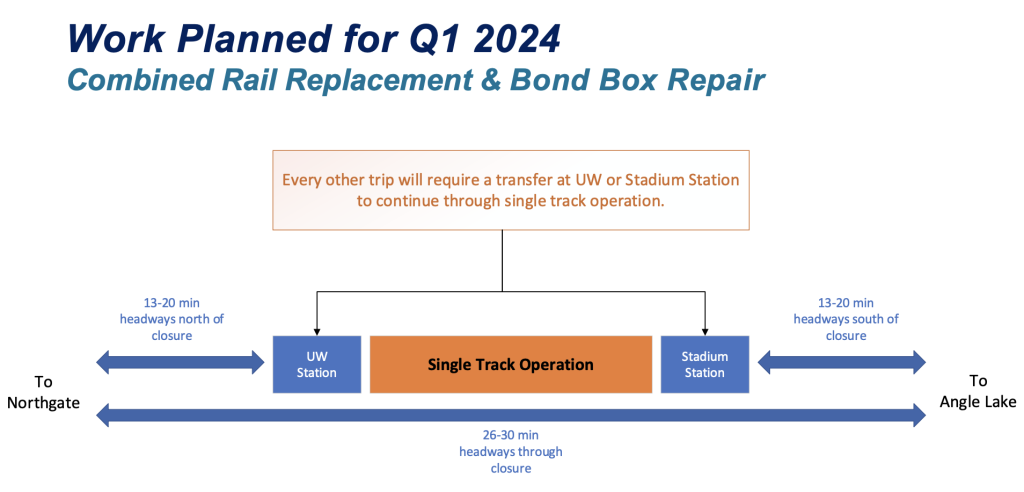

Seattle’s transit riders still have two full weeks left of planned disruptions to Sound Transit’s high capacity light rail spine, the Link 1 Line. Those disruptions, deemed necessary by Sound Transit to make safety and maintenance upgrades to their downtown Seattle transit tunnel, have already brought significant headaches to riders, particularly on weekday evenings when passenger demand is at its height. Originally, the agency announced that it would able to run trains through downtown every 26 minutes on weekdays, with more frequent service north of Capitol Hill and south of the Chinatown-International District.

In practice, riders found much more unpredictable schedules, intense overcrowding, and delays that compounded with trains operating extra slowly during single-tracking. The maintenance work began Saturday, January 13 and will last until February 4.

With 26-minute service slipping to 30- and 35-minute service during peak hours, Link’s capacity to move passengers through downtown has dramatically decreased, even as demand remains high. In its communication with both riders and the Sound Transit board, agency staff seemed to be pointing to the need for a certain subset of riders to give up on the system and find other ways to get around the region that don’t involve Link.

“We know that the disruption has been a challenge for our passengers especially during the first days back to work this week, and we appreciate our passengers’ patience during this time,” Russ Arnold, Sound Transit’s chief systems delivery officer, told the board’s rider experience committee last Thursday. “We hope that as passengers get used to the change in their travel, initial problems will tend to smooth themselves out.”

Sound Transit spokesperson John Gallagher echoed the same sentiment in a statement to Mike Lindblom of The Seattle Times, saying Sound Transit hopes things will “sort themselves out.” Gallagher offered the direct advice to switch to buses if they’re available, even as the region’s bus network has specifically evolved to rely more and more on Link service to bridge final connections, particularly to downtown Seattle.

The primary reason that the agency says it hasn’t been able to deliver the 26-minute frequencies it promised during peak hours is that overcrowding is slowing down trains — at stations, dwell times are higher than normal as riders try to squeeze on and off packed trains, prompting the appearance that Sound Transit is ultimately hoping that many of its normal riders give up on trying to use light rail during this disruption, even as parallel bus routes have been scaled-back in recent years with new station openings, and many cross-region trips require using light rail for at least one leg to keep the trip to a reasonable timeframe.

This isn’t the first time that Sound Transit has overpromised and underdelivered on frequencies, either temporary or permanent. Last year, 15-minute planned service around maintenance work in SoDo became 20-minute service after the schedule couldn’t be maintained. And in Tacoma, long-promised 10-minute service on the T Line to Hilltop became 12-minute service by the time the line’s extension opened last year, after the agency had trouble providing what it had promised with the available number of train cars.

This current disruption, which includes a downtown bus bridge subbed in for trains on the weekends, ultimately provides a preview of how the agency will deal with intense overcrowding that it expects to see on Link this fall with the launch of service to Lynnwood, as well as how Sound Transit will deal with service disruptions more generally as the spine continues to grow. The “deal with it” nature of the current situation makes it very easy for a rider to justify giving up entirely.

At last week’s committee meeting, Suraj Shetty, the agency’s executive director of operations, responded to a question from Fife Mayor Kim Roscoe on communications that Sound Transit has received from frustrated riders using the system during the disruption.

“In looking at the comments today, there seems to be a large concern that the communication didn’t match the service that was delivered,” Shetty said. “In particular on Tuesday, when we had a higher peak crowds…there were higher dwell times and therefore the 26 minutes that we had advertised were not materialized, because it took longer to clear the trains because of the larger crowds. And so there were periods in the peak periods where we weren’t hitting our times. So I gathered the public comments said you communicated one thing but your service turned out a different way.”

Shetty noted that things had improved for Wednesday and Thursday, but intense crowds during the evening commute remained. Shetty’s answer prompted Roscoe to ask how the agency had not accounted for increased dwell times due to crowds in the preparation for this disruption. “How did the modelling miss that?” Roscoe said.

Pamela Wrenn, deputy project director of service delivery, replied that they had actually expected longer dwell times but erred on the side of advertising the service levels they’d be able to provide throughout most of the day, setting riders up to be disappointed during times of the highest ridership. “I think it was known that we might not meet our targets during the very, very crowded PM peak, for example, but if we changed our headways to be longer then we wouldn’t be providing the best possible service during all the other times of the day,” she said.

In other words, Sound Transit risked not being able to deliver what it was promising at the most critical times of day for the sake of consistency. But ultimately, this risks only further undermining the trust that riders have in Sound Transit as a whole, with most only willing to endure incorrect arrival times and inaccurate information on a limited basis if they have other options. As the system grows, there are no signs that Sound Transit is getting more resilient in responding to service disruptions, even long-planned ones.

Weekend service, with twin articulated buses providing shadow service at all downtown stations while the transit tunnel is completely shut down, has gone relatively more smoothly. Trains are able to operate more frequently than 26 minutes and the system has seen smaller crowds across the board. But operating shadow service during the entire three-week maintenance window doesn’t appear to be possible right now due to bus operator staffing levels.

Zooming out, a three-week disruption is the blink of an eye, and getting this needed maintenance done before the launch of Lynnwood Link this fall is clearly the right call. But whether Sound Transit’s management of this specific disruption will do more harm than it otherwise would due to lack of consistency and clear communication, that remains to be seen. For a region becoming increasingly reliant on this critical piece of infrastructure, handling disruptions like this will be one of the biggest tests that Sound Transit faces over the coming years.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.