Let’s be honest, most folks have zero concept about the size and shape of their city. Some of that comes from a difficulty in attaching math and proportions to things we see every day. A bit probably comes from the disconnection from the land created by speeding traffic. Mostly, it’s that folks have better things to do than think about than the number of acres in their neighborhood park.

Unfortunately, misunderstanding the proportions of the city leads to really terrible policy decisions. Things that sound like simple compromises — a percentage here, a half-distance there – results in drastic changes to rules. Doing a better job picturing some of these ideas in our heads will go a long way in preventing dumb policies and gutting legislation. Spoiler: there will be math. So, let’s start with a basic idea.

How big is an acre?

Seattle has 285 zones, of which 46 apply to less than two acres. In a city that’s 53,620 acres, it means 1/6th of the zones are specifically tailored for 0.3% of the land. Unfortunately, those numbers just float in space for most people. Let’s pin down what an acre actually looks like.

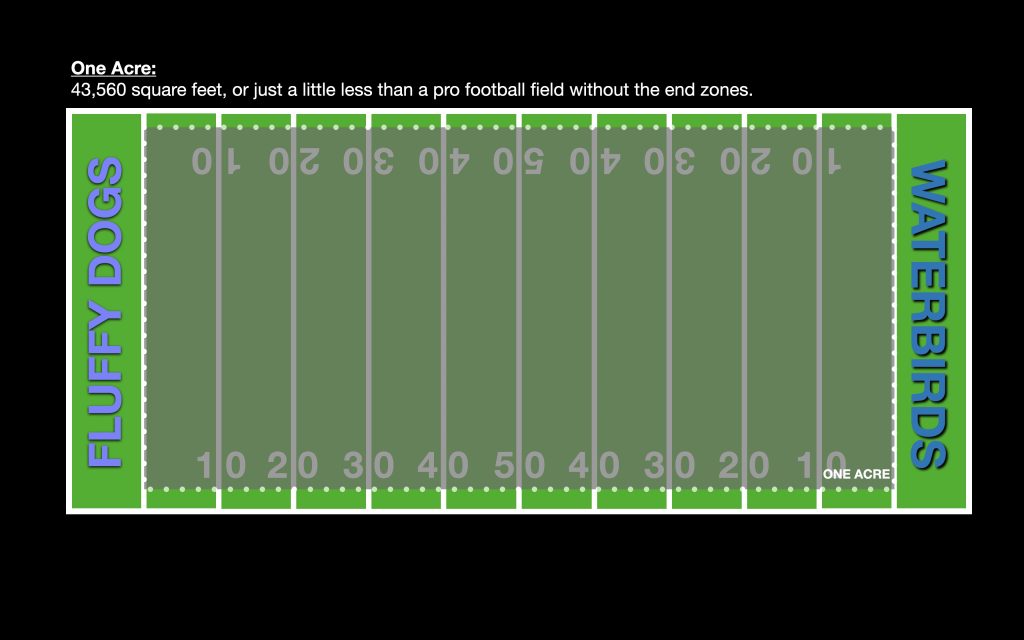

An acre is 43,560 square feet, traditionally measured as a rectangle 66 feet across and 660 feet long. The Imperial measurement system is ridiculous, and these wacky numbers all derive from yoked oxen and medieval metal chains. The upshot is that an acre covers a square about 210 feet on a side, or a field about 100 yards long and just under 50 yards wide.

Conveniently, the playing area of an American Football field is 100 yards long and 53.3 yards wide. An acre is just a smidgen smaller than a regulation football field without the end zones.

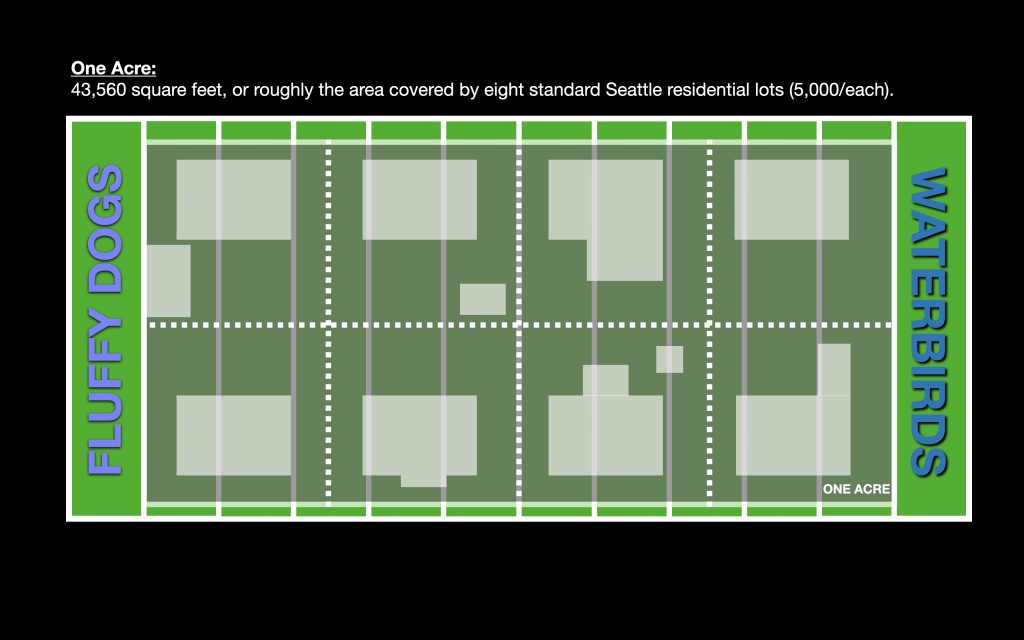

That helps a lot, because the yard lines and hash marks allow us to put some shape to the discussion. A classic Seattle housing lot is 50 wide by 100 feet deep, or 5,000 square feet. That would be a little under 1/8th of an acre. Think of a block of detached city houses and every eight craftsmans is a football field, or one acre.

The average downtown Seattle block size is 240 feet by 240 feet, or 1.3 acres. That would be about a football field with the endzones. This is a bit difficult because we look down on a football field with cameras and up at the big towers in the city. So let’s change that a little, the footprint of the average grocery store — without the parking — is about the same as an entire city block. As I’ve noted before, it’s further to get from the parking lot to the milk fridge at most grocery stores than it is to walk a block.

What all can you fit in one acre? The average Wal-Mart runs about 150,000 square feet, so they’re three acres. Usually they are set in 15-17 acres of parking, a number that even Wal-Mart would like to reduce. But 150 spaces of parking plus the drive lanes is an acre. That’s three rows of 50 cars.

Surprisingly, the term “acre” does not show up in the zoning ordinance very often. It is really only used as a threshold for getting a permits in shoreline work and there is a minimum 15 acre size to certain rezonings.

Getting the size of an acre correct in our heads helps with some other concepts. Of course, an acre is the same size in town as it is in the suburbs. However, a city acre is a lot more productive than suburban acres. Strong Towns has extensive analysis showing where a city’s revenue comes from, and surprise!, it’s not from gour-unit per acre McMansions. Downtowns subsidize suburbs.

For our friends in Canada, it takes about two and a half (2.47) acres to make one hectare, the metric measurement of area. Being sane human beings, a hectare is a square of 100 meters on a side and 100 hectares makes a square kilometer. Just bathe in the rationality of such a system for a moment. Most sports fields that are surrounded by a 400m running track are a full hectare, not including the track.

Floor area ratio (FAR)

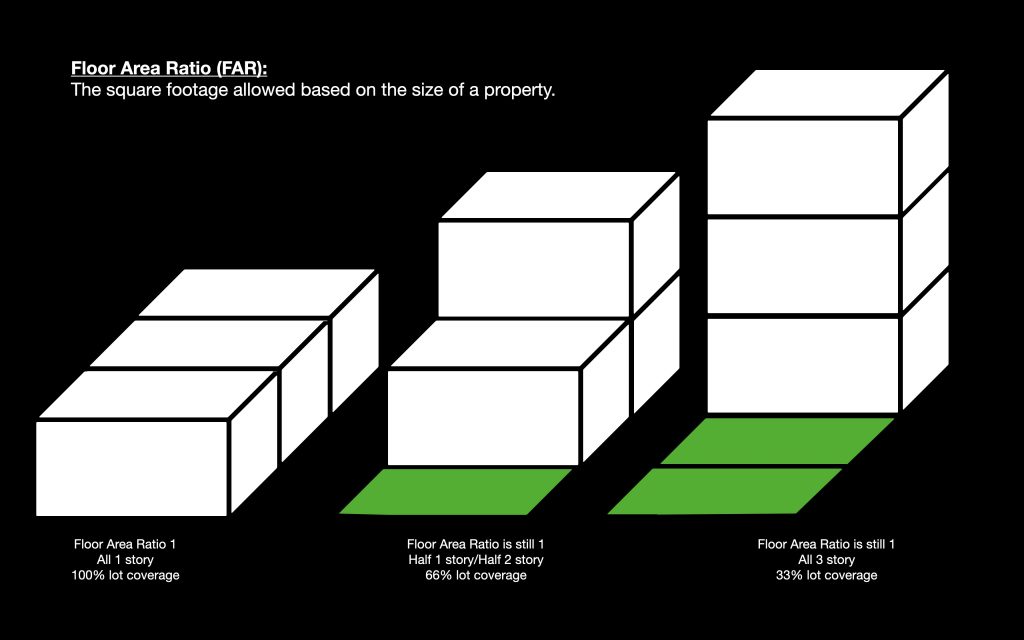

While the zoning code reserves acres for big projects, almost every unit is impacted by a different measure: Floor area ratio or FAR. FAR is simply the square footage of a structure divided by the square footage of the lot it’s built on. Most residential areas run an FAR of 0.5 to 1, essentially saying your house can only be between half and the full the area of your lot. The traditional city average 1/8th acre lot size would then allow between a 2,500 square foot (sf) house to a 5,000 sf house.

Most smart urban planners use Legos to describe FAR. A single layer of Legos over the whole base plate gives an FAR of 1. You can rearrange the entire mess into a single spire and, if you haven’t added or subtracted any pieces, still have an FAR of 1. There are other rules like height limits and setbacks that prevent either the wall-to-wall block or the wobbly spire, but most zoning is underpinned by FAR.

Again, here is where little changes make a big difference. It seems a small compromise to go from an FAR of 3.0 to 2.5 may sound reasonable until you do the math. A parcel of 30,000 square feet, losing 0.5 FAR means lopping 15,000 square feet of the project. That could be a dozen apartment units that could make or break a project from a financing perspective.

On the opposite side, adding 0.5 FAR can make a project feasible or more interesting. To preserve an exceptional tree on the lot, the developer of the new apartment building 904 NW Market near Gilman Park was allowed to add 0.5 FAR. The approved design has a literal half floor that turns the ground-level west end apartments into two-floor townhome style residences. The bonus added 14 bedrooms that make the units more fit for different size families. Designs that did not have the bonus were heavy on 1 bedroom apartments.

The area of a circle.

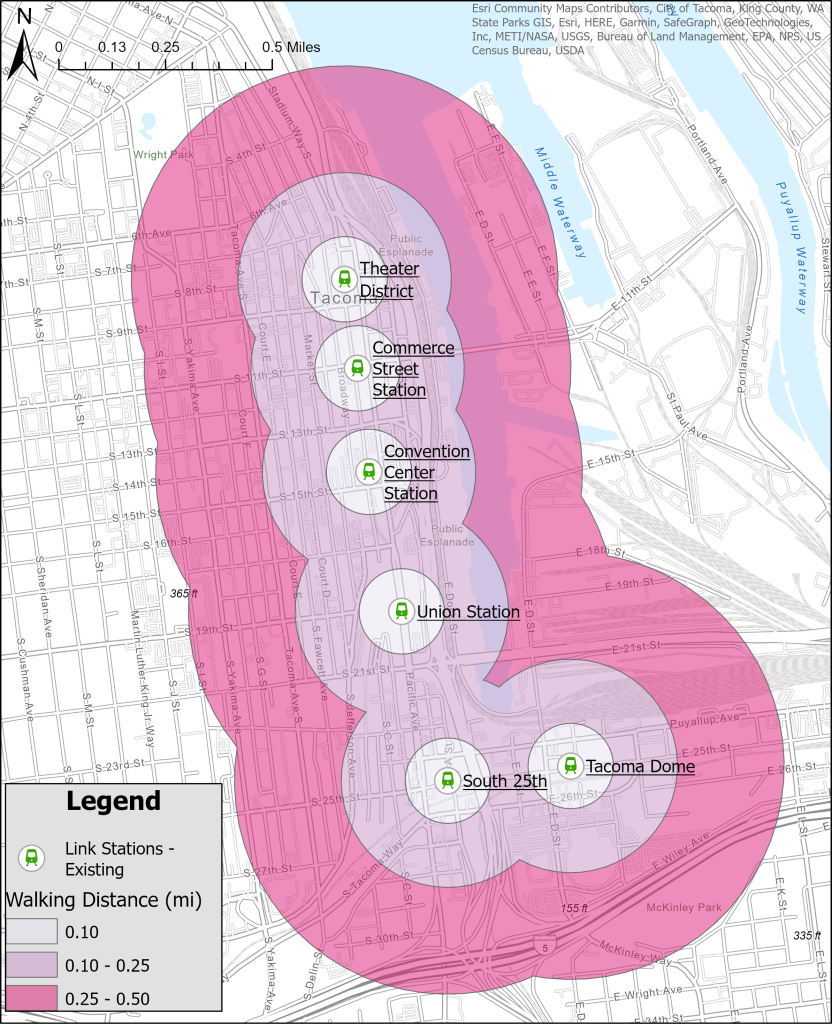

Confusion about the concept of area has allowed the legislature to give enormous concessions to anti-housing groups. We’ve covered this before as the Washington Legislature winnowed down housing bills in the 2023 session, but since we’re back in Olympia and looking at making rules about transit oriented development, let’s talk about the relationship between radius and area of a circle.

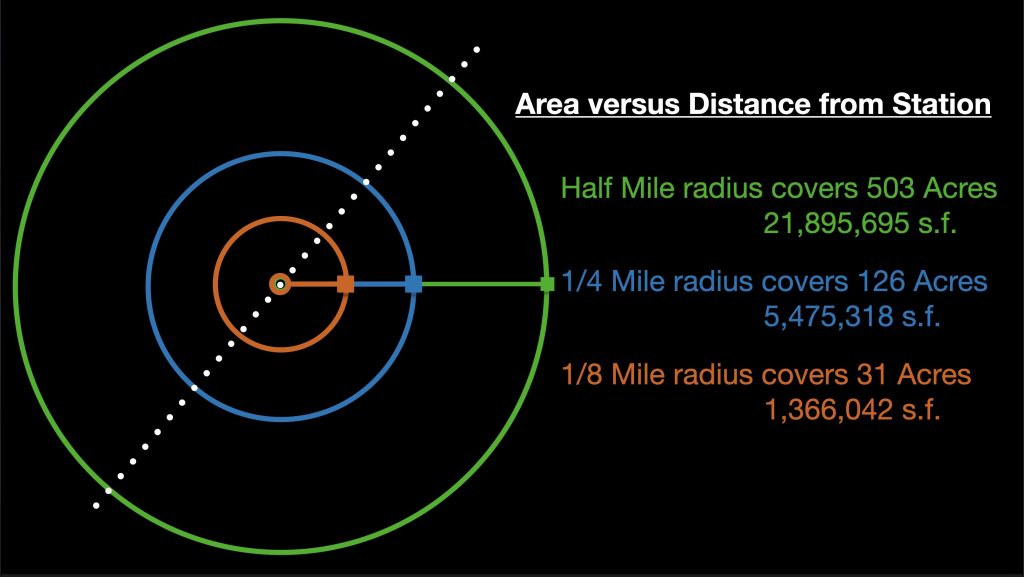

The area of any shape is length times width. So look at your nearest tile floor, and start counting squares. If you take one tile edge wide and another tile edge wide, you get an area of…wait for it… one tile. Two tile edges wide and two high — doubling the edges — turns into four tiles. Doubling it again — four tile edges on a side — quadruples the number to 16 tiles. Same applies to circles (with that mysterious pi thrown in). Doubling the radius quadruples the area. It’s the reason why a 9-inch pizza is a personal pan, an 18-inch pizza is an XL-family sized, and a 36-inch pizza is a dare.

If doubling the sides quadruples the area, the same is true in reverse. Halving the distance of a circle quarters the area.

This concept is vital when talking about compromises in legislation. Say a proposed law allows new homes in a half mile of a bus stop. The simple act of decreasing the area of effect from a half-mile to a quarter-mile doesn’t just half the number of homes possible, it removes an eye watering 75% of the possible developable area. If another compromise reduced the area to one-eighth mile, that’s another 75% reduction in the area of impact. An eighth-mile area is 94% smaller than a half-mile area. What sounds like meeting half-way is actually giving away the entire argument.

The impacts are significant. Reducing the area affected by these bills by 75% or 95% guts the purpose of expanding affordable, walkable housing. When one takes into account streets and the stations themselves, 31 acres really whittles down to a couple of additional units. Not the density that can really hit a tipping point to bring services and amenities into a walkable area.

For Seattle-local context, Green Lake (including the lake) and Woodland Park together are about 500 acres. Just Woodland Park is about 100 acres. And the exhibits at Woodland Park Zoo consume about 35 acres. An argument could be made that a half-mile circle is too big because 500 acres exceeds the size of several municipalities in the Seattle area, specifically Yarrow Point, Hunts Point, and Beaux Arts Village. A counter argument is that there is no reason for jurisdictions of that size with zoning authority to exist within a Growth Management Area (GMA) during a climate and housing crisis.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.