Transit conveys culture as its conveys passengers. The former Russian capital provides some lessons on how the Seattle region could do better.

Seattle has begun constructing a major light rail system with Link, defining the contours of its urban development for generations. Every mile of track laid and station opened speaks to the region’s values. At the moment, a single word best summarizes their message: serviceable.

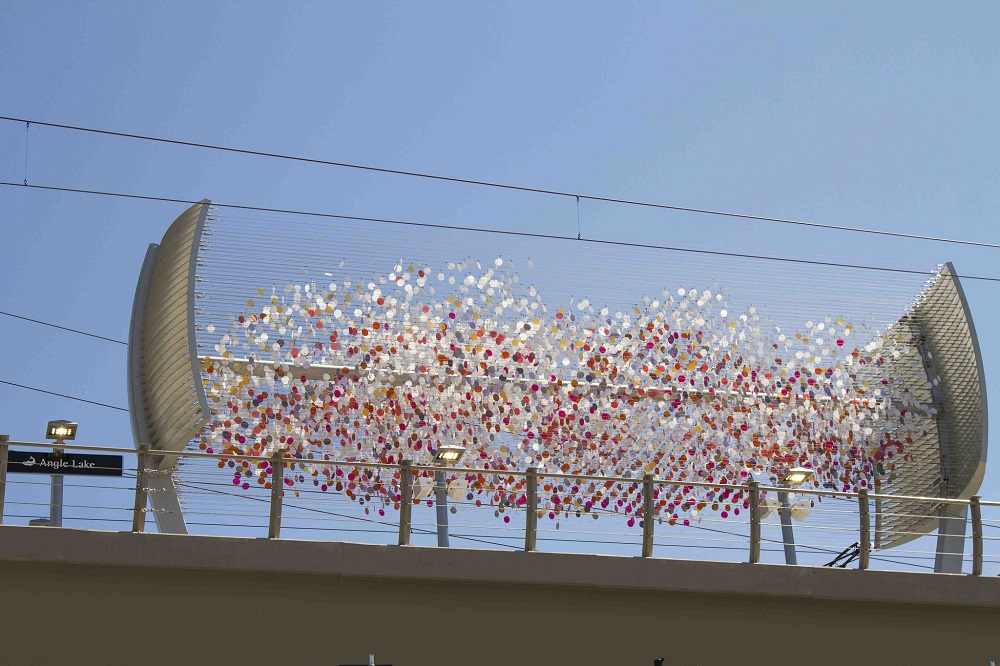

Link’s stations are largely utilitarian; they permit reasonably comfortable travel. Some have interesting art, but the overall system lacks a coherent theme. Pieces celebrating multiculturalism are, often literally, tacked on rather than embedded into structures, causing one to question the stability of the ideological foundations.

The literal foundations of multicultural representation are so weak that wind destroyed Beacon Hill’s Common Threads installation back in 2014, leaving it missing for three years. If we can lose our values with the wind, how tightly do we hold them?

This is not the case globally, even outside exceptionally wealthy countries in Western Europe and East Asia. From Istanbul to Buenos Aires, governments have utilized transit spaces to build legitimacy. Beautiful lasting architecture wordlessly teaches historical and ideological narratives to massive audiences, if used thoughtfully and intentionally.

Transportation infrastructure frames every interaction an individual has with the world. It defines how we conceptualize our physical negotiation with geography, augmenting the region’s character by framing our motion between locations. This opens up opportunities for builders to intentionally design public perceptions of a region’s character, an opportunity dynamic and purposeful governments around the world take.

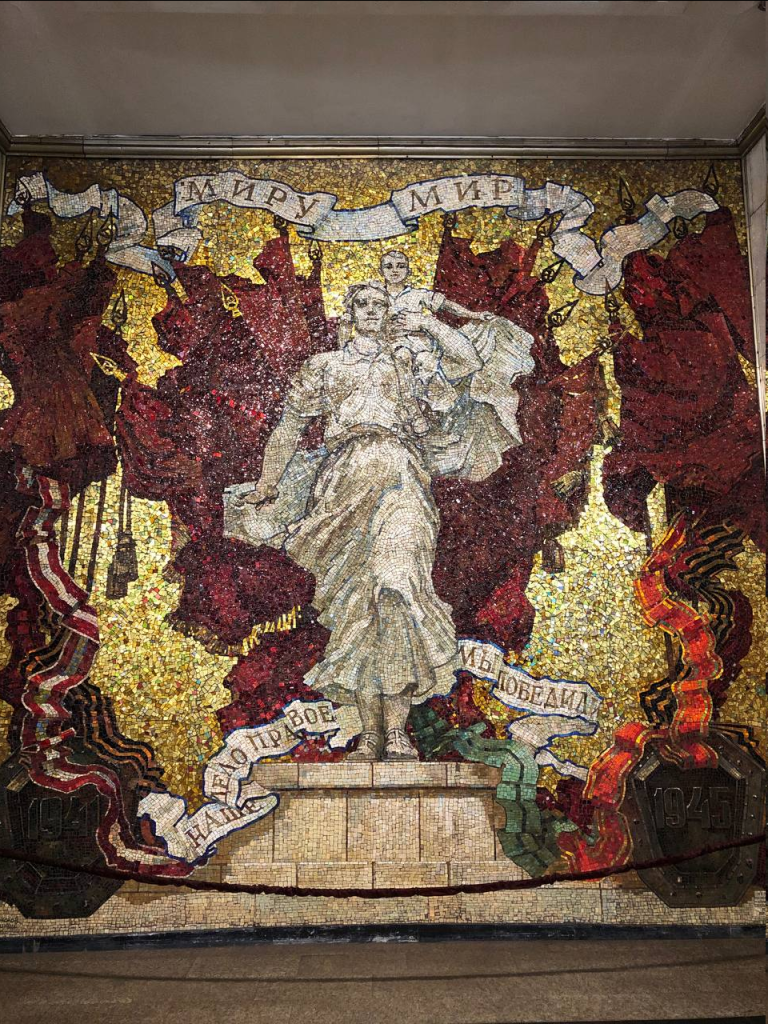

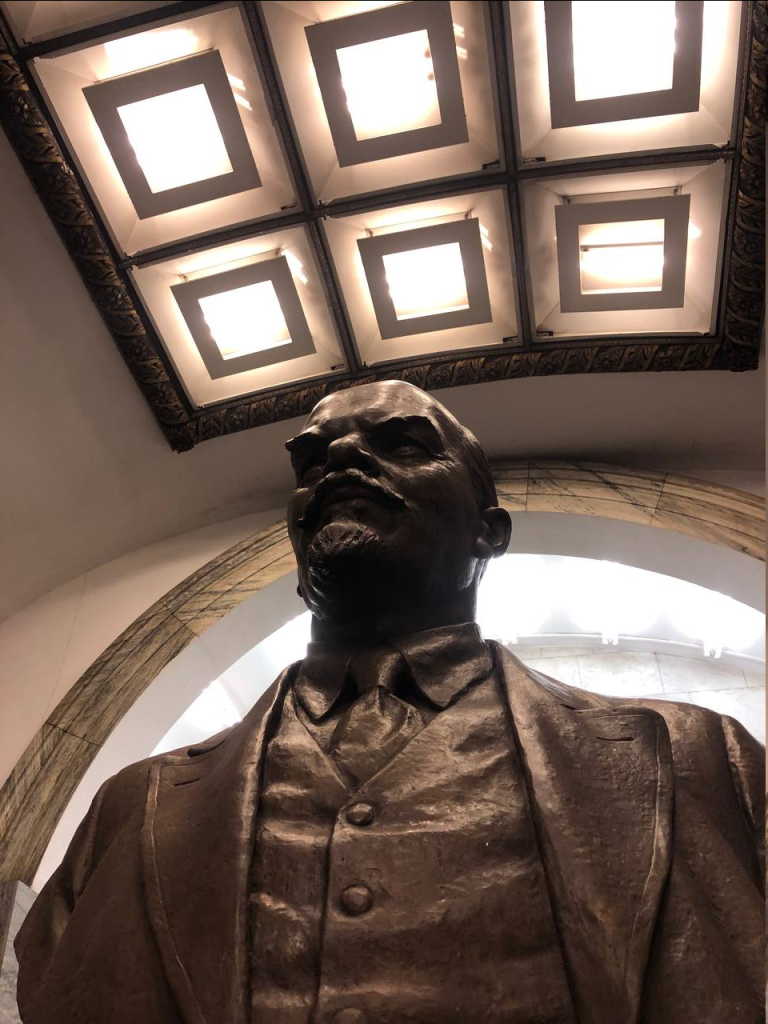

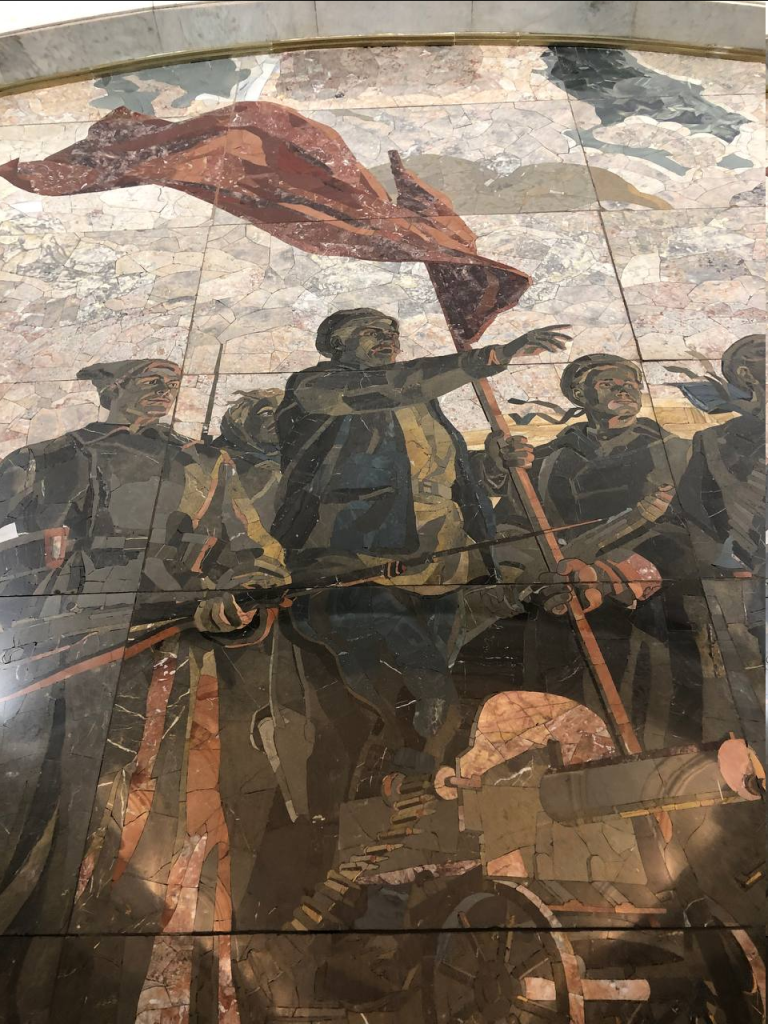

Perhaps more than any other country, the Soviet Union understood the community building capacity of public art. Its most lasting messages come from how the government integrated local history and culture into its artistic messaging. Having lived and commuted in Saint Petersburg, Russia for seven years, I’ve gained an intimate familiarity with the themes built into the system.

Grandiose neoclassicism had guided the hands of Soviet draftspeople for an ideological purpose: They mixed revolutionary themes with imperial palatial architectural styles to demonstrate that the Communist revolution had liberated the empire’s wealth from the confines of palaces and applied it to public spaces. They had a specific intentional message which powerfully delivered a compelling narrative about the country’s history.

Even after Khrushchev’s “order against excesses in architecture” in 1955, the government continued building wide platforms with high ceilings featuring art celebrating local workers and regional history. Why? The opportunity to win people over to a narrative about themselves wasn’t an opportunity to be wasted, even during a period of austerity. This has remained true well after the collapse of the USSR, meaning the decision to physically liberate grandeur from the empire’s palaces has been a more permanent revolutionary act than any party platform.

Seattle’s Link stations exhibit pleasant creations by local artists highlighting select aspects of the region’s peoples and environment, but they are not organized to communicate any deeper narratives about the city’s character. Instead, they inoffensively achieve what Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s director of communications, Jamie Housen, said the mayor intends to accomplish with public art: “beautify shared spaces in Seattle, create opportunities for artists, and add vibrancy and character to our neighborhoods.”

While beautification and artistic patronage are laudable goals, the city has missed a rare opportunity to physically define the region’s values while educating residents and visitors alike. This isn’t the fault of the artists – they have fulfilled their duties by creating beautiful and innovative pieces on behalf of their patrons. It is the fault of their patrons for not providing more direction, allowing great works to get lost in a chaotic din of disparate ideas.

By contrast, ideology and architecture converse loudly and deeply in the halls of Petersburg’s metro system. Far more often than Lenin, a symbol in and of himself, one finds visual depictions venerating common working people – scientists, teachers, oil workers, electrical engineers, miners, and athletes. Though by no means a panacea for classism, the enduring beauty of these tributes has permitted the better angels of their ideological natures to transcend the often flawed political individuals who built them. They indelibly stitch what had been an ideological statement, respect for proletarian workers, into the region’s culture and history. It is truly revolutionary to behold the architecture of imperial palaces honoring the people who built them, rather than the patrons who ordered them. That is what an effective architectural ideological statement looks like.

The Mukilteo Multimodal Ferry Terminal provides a model for how strong ideological statements have been made in Washington. Here, collaboration with indigenous communities has resulted in a powerful physical message: Indigenous nations have a role in defining the region both historically and presently. The building celebrates and honors the communities which have striven to advocate for responsible environmental stewardship and social justice for millenia by incorporating their input into the building’s environmental and aesthetic design, delivering through wordless awe a lesson otherwise learned through hours of reading.

Far from resting on our laurels after projects like Mukilteo, we should constantly strive to step further. While the terminal was a success in the eyes of Kerry Lyste at the Stillaguamish Cultural Resources Department, they said the whole project could have been improved in numerous ways: keeping more faithfully to the original longhouse concept, integrating more artwork into the structure, and hosting an opening ceremony where more people could have attended.

More strongly, Lyste emphasized: “Does [the project’s success] erase the fact the treaty was signed a short distance away? Or that Japanese Americans were subjected to ethnic cleansing a short distance away (Japanese Gulch) similar to some of the suffering caused Native Americans in this vicinity? However, it is a step in the right direction.”

While public art and consciousness raising alone will not alleviate society’s ills, any steps in the right direction are worth taking: They extend the distance that can be traveled in the future.

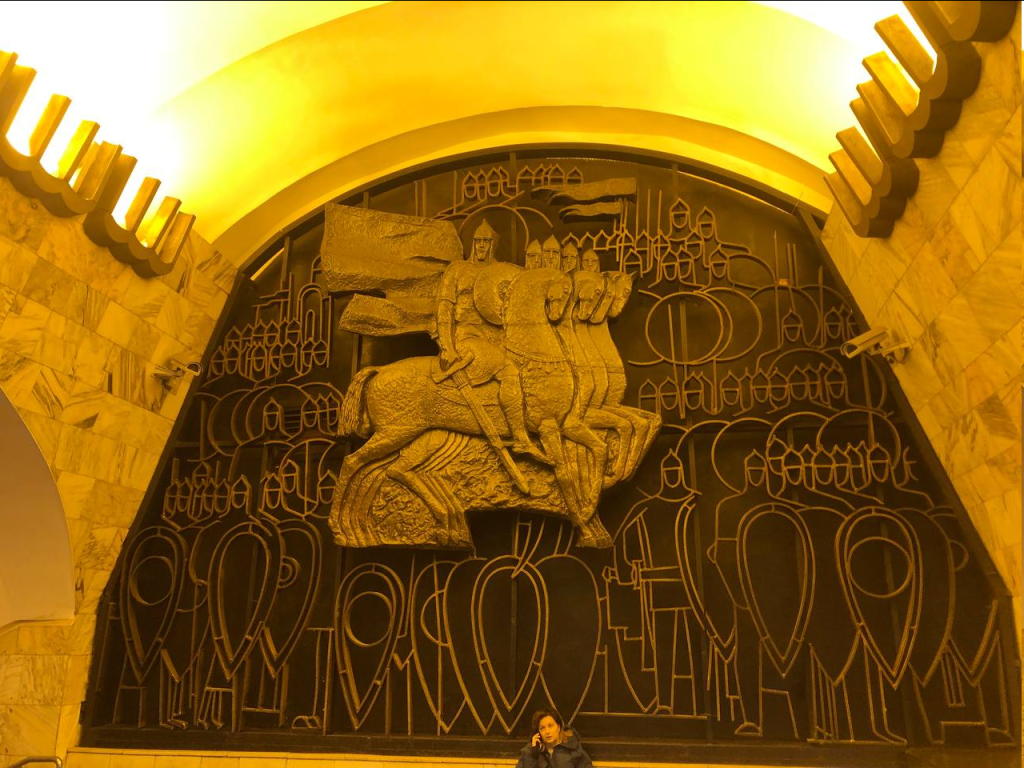

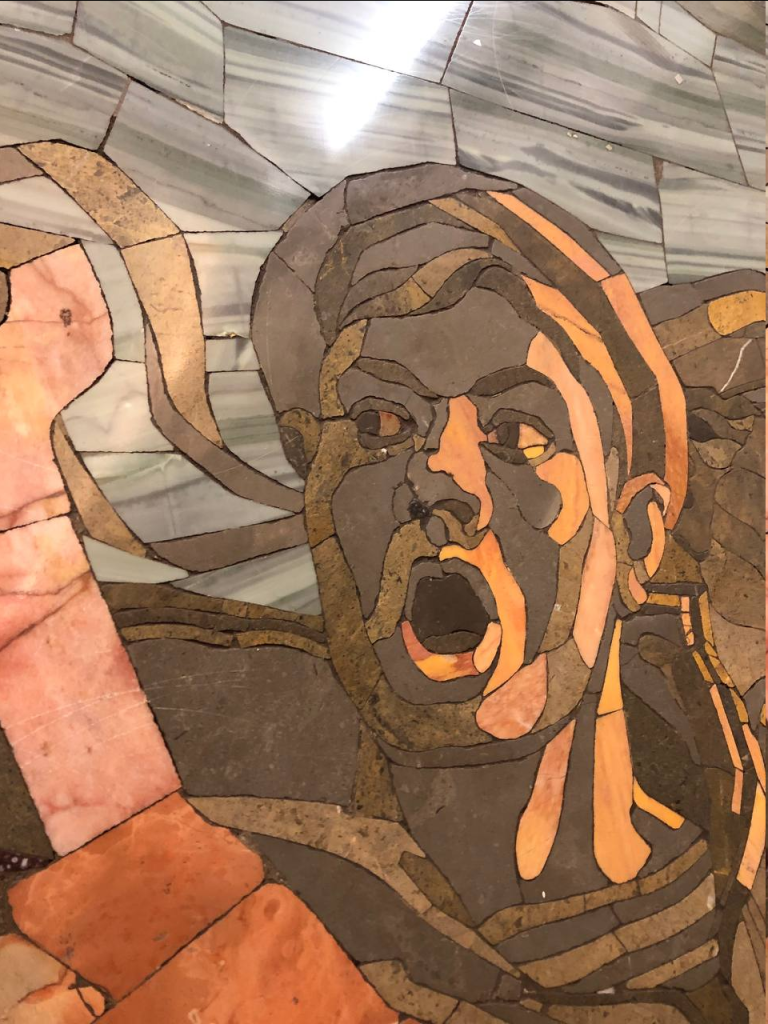

In addressing how historical narratives can both create beautiful public spaces while taking steps to heal historical trauma, Saint-Petersburg offers the form of Alexander Nevsky. He holds unique local cultural and historical significance for his victory at The Battle on the Ice against marauding German crusaders, mirroring the Soviet defeat of the genocidal Nazi German invasion from 1941-1945. The Nazi invasion has left a deep psychological scar on the city which persists to this day: For three years the Nazi armies had cut off the city during the horrific siege of Leningrad, and millions of men, women, and children died, many starving to death.

The physical scars still manifest in survivors whose growth was stunted due to childhood malnutrition, to say nothing of buildings and graveyards. Using Nevsky as a symbol of overcoming those horrors can help people make sense of and overcome their own inter-generational traumas by framing their suffering as heroic: You are not helpless victims, you are victorious survivors.

Unlike during the failed Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, the invaders of the Pacific Northwest won. This makes the task of honoring historical legacies more complicated and means any artistic displays venerating its history should be developed in consort with representatives of the communities which have been historically affected by the brutal policies of Washington and the United States.

Mukilteo Ferry Terminal, again, provides a helpful example of what this collaboration could look like moving forward. If Seattle were to emulate Petersburg’s celebration of figures who fought colonization, honoring Chief Leschi for his stalwart resistance to injustice could be a start. However, tributes to nations must always be controlled by those nations themselves, so the Nisqually must play a central role in developing the messages behind his representation. As Russians control the narrative of Nevsky, the Nisqually should control the narrative of Leschi.

Along with honoring the heroic survivors of war and fighters for liberation, literary figures play a key role in shaping the memory and context of both Petersburg and Seattle as cities. In Petersburg, the metro’s planners have striven to exceed nominal dedication by incorporating specific thematic elements into station architecture: Dostoyevsakaya’s dark stonework and black street lamps visually convey the dismal atmospheres of his stories, Mayakovskaya’s red mosaic walls emit the vibrant energy of his revolutionary poetry, and bright romanticism fills the halls of Pushkinskaya with serenity. The symbolism embedded into the structures invests these spaces with a deeper sense of place, making waypoints feel more like locations in and of themselves.

Emulating this in Seattle, the city could incorporate the thematic elements of writers like Carlos Bulosan. His powerful yet tragic life story of immigrant and labor activism more than warrants the public honor and recognition of a thematically designed transit station.

Architectural tributes – whether to artists, leaders, or common working people – gain meaning from the level of craftsmanship invested into their creation. Merely scribbling Bulosan’s name onto a concrete wall would demonstrate casual disregard at best or thoughtless contempt at worst. Conversely, a good-faith historically significant architectural tribute invests time, knowledge, and resources into creating beautiful art in mesmerizing detail, allowing the subject to transcend itself. The builders of the Mukilteo Ferry Terminal and Saint Petersburg’s metro system understood this: The goal of a tribute is to teach through awe. The more this is done, the more political and social capital is gained by the builders.

Providing workers the opportunity to earn a living by building a functioning metropolitan rail network is laudable in and of itself, but it is positively inspirational to fund a project which builders would proudly carve their names into. In a transfer hall at Spasskaya station, the architects and designers of the system have had their names carved into a massive stone disk. Creating something both aesthetically magisterial to the eye and imperatively vital for society, so historically prescient and comprehensively humbling that the names carved into it earn respect for eternity, indicates something far more than a waypoint has been built.

Massive infrastructure projects not only provide effective transportation in the immediate-term and nation building potential in the long-term, they lend the governments which build and maintain them medium-term broad-based legitimacy: Infrastructure wins new converts to a cause or party by proving the functional viability of its principles. A government which can physically demonstrate its capacity has an easier time getting reelected and controlling the narrative.

In order to gain some insight into public perceptions of the system in Petersburg, I conducted an informal survey of 18 metro riders, ESL students, and colleagues of mine and my fiance’s across ages, genders, and professions. The consistency in some answers was noteworthy, especially because everyone told us they use the metro for one main reason: It’s a fast, convenient, and cheap way to avoid traffic. When I asked whether aesthetically pleasing architecture positively impacted their transfer experiences, because transferring is widely considered one of the most annoying features of transit use, all but two said it did.

The most consistent and uniform complaint was how long it took to open new metro stations. Even before conducting the survey, I’d heard many people complain about how Moscow regularly receives two to three new stations every year while Petersburg gets a couple every decade. However, this is where legitimacy, transport, and architecture come together: Respondents forgave their points of contention because of the speed, reliability, and aesthetics of the system. If Link could deliver all four of those points – fast construction, high speed, stable reliability, and aesthetic value – it could provide an effective political foundation for whatever party achieves that outcome.

Beautiful architecture serves functional political purposes: It frames our interaction with government services and allows us to forgive their shortcomings. Looking at the bigger picture, it can elevate a waypoint into a location and carve ethical principles into stone, preserving values beyond the lifetimes of problematic individuals. Transportation infrastructure has already stitched itself into the fabric of Russian and American national consciousnesses, and what our societies build today irrevocably weaves the present into our national futures. We should strive to spin beautiful tapestries.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.