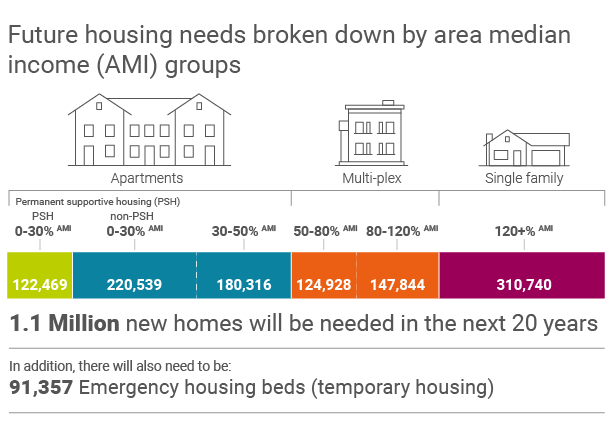

A proposal that would shift the system of accountability around managing housing and job growth in Washington is already receiving strong pushback from local elected officials and their advocates in Olympia as it advances at the state legislature. The fight highlights the degree to which city, county, and town governments will try and retain their current level of control over housing and land use decisions, even in the face of an intense deficit in available housing units and a need to accommodate more than one million new housing units across the state over the next two decades, according to the most recent state estimates.

House Bill 2113, introduced by Representative Jessica Bateman (D-22, Olympia), would empower the state’s Department of Commerce to be able to certify whether cities and counties are properly managing growth in accordance with state housing law and the 1990 Growth Management Act (GMA), opening the door to state sanctions like disqualification for state and federal grants. Such a change would represent a shift away from the current process, where disputes over local land use plans are resolved by residents or advocacy organizations at the Growth Management Hearings Board, in processes that can take months if not years to be resolved. Even if the Commerce department, which oversees growth planning at the state level, knows a city is likely not complying with the GMA, there’s no avenue for the state to be able to take action to correct it under existing statute.

Bateman’s bill also includes a strong incentive for local governments to get their plans in compliance — a “builder’s remedy.” Under the bill, cities and counties found to be out-of-compliance with the Growth Management Act that do not take corrective action to fix their comprehensive plans will have to grant a building permit to anyone looking to build a housing project in a residential area of that city, as long as a certain number of units are set aside for lower-income residents. If cities do want to control development within their borders, they have to stay within the four corners of state law.

To qualify for the builder’s remedy, rental buildings would need to set aside 20% of their units for households making 60% of the area median income or less, or consist of a fully affordable building to households making 30% of the area median income. Developers building housing projects available for permanent purchase would be able to get their permits approved if at least 20% of the units are able to be purchased by people making 80% of the area median income or less — $80,750 for a family of two in King County,

But additional oversight, along with that strong new incentive to remain in compliance, isn’t sitting well with local jurisdictions who don’t want to change or relinquish any of their local control over land use.

“This is a major change in the way Growth Management has been done in this state,” Carl Schroeder, lobbyist for the Washington Association of Cities or AWC, told the committee Monday.

AWC has been a leading voice at the legislature for retaining local land use control, though in recent years their strategy has shifted from stopping bills to reducing their impact on local cities. But in the case of HB 2113, Schroeder came out in full opposition.

“Since the GMA was put in place in the 90’s, the goal, or the structure, was to ask local governments to do the planning following guidelines and responsibilities set out by the state,” Schroeder said. “This would effectively make this state a partner with those growth plans… with a veto.”

Of course, the state is a partner in growth plans already, with the Department of Commerce providing grants to help cities with local planning, and offering guidance to cities when they ask for recommendations or assistance. And the state already has a role in reviewing the Shoreline Master Program elements of local cities’ comprehensive plans, which HB 2113 took as its model, according to Rep. Bateman.

Salim Nice, the Mayor of Mercer Island, called HB 2113 a bill that “not only contravenes the spirit of the Growth Management Act, but also introduces redundancy and undermines the crucial public involvement in local planning processes.” Nice was one of the most outspoken local officials last year on HB 1110, the state’s successful missing middle housing bill, and this year is also pushing back on HB 2160, which would loosen zoning restrictions within a half-mile radius of light rail stations like Mercer Island’s.

“Perhaps most concerning is the way that HB 2113 sidelines the public process,” Nice said Monday. “The success of the GMA hinges on robust public participation, ensuring that the voices of community members are heard and considered in shaping the future of their neighborhoods. However, HB 2113 proposes a top down approach where decisions on housing element compliance are made far removed from the local context and community input.”

But the bill doesn’t preclude public participation in local comprehensive plans, and state intervention would only happen when cities are running astray of clear direction from the state legislature.

Also coming out against the bill this week was the City of Bellevue, via its lobbyist Briahna Murray. She framed the proposal as one that is not fully baked, and cited the potential for it to create considerable uncertainty for jurisdictions who are set to update their comprehensive plans before the end of this year, which is most jurisdictions in central Puget Sound. Murray asked for more process before moving forward with a change like HB 2113.

“Most of the other significant changes to the Growth Management Act have gone through significant stakeholder work before coming before you, [the] City of Bellevue does not believe that this proposal has gone through that same level of stakeholder work and that it should,” Murray said.

Bellevue was also a jurisdiction that pushed back on HB 1110 last year. “I’m just really concerned with the impact to the character of our neighborhoods,” Bellevue Councilmember Jared Nieuwenhuis, at the time the city’s Deputy Mayor, said. “Those people that have earned and saved, like myself, for many many years because I wanted to live in Bellevue but I couldn’t afford to live in Bellevue until I did everything I could to put myself in a position where I could finally get there…and then when I get there, I’m not sure I want a sixplex right beside me.”

Ultimately, in response to pushback like Bellevue’s, state legislators watered down HB 1110, lowering the new minimum level of residential density in a city of Bellevue’s size from six to four units.

Both Nice and Murray framed the state’s involvement in growth plans as unnecessary, with Nice calling it redundant. But affordable housing providers, including leaders at nonprofits charged with creating housing for people most in need of it — those directly exiting homelessness — cited real barriers to getting projects approved that HB 2113 could be able to remove.

“There’s currently very little support from the state if a housing project is being held up by onerous local regulations,” Dan Wise, an agency director with Catholic Community Services, told the committee. Catholic Community Services manages dozens of permanent and transitional housing projects throughout Western Washington. “I’ve had projects stalled by municipalities because they were too close to other social services, near a private school, or just not what the city planners wanted to see developed in that neighborhood,” Wise said. “There’s currently very little ability to appeal these locally-imposed roadblocks. This bill responds to the unfortunate reality that some communities have exploited a lack of state compliance regulation.”

Wise was joined by representatives from the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance, the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, and Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King and Kittitas Counties in support of the bill.

Futurewise, the statewide land use advocacy organization that regularly files appeals on behalf of local residents challenging moves by local governments that enable sprawl and move the state away from enabling more compact communities, supported the bill on Monday.

“We have spent years, [and] millions of dollars, working both with local jurisdictions, but also forced to appeal when they make bad decisions: either they’re not listening to their constituency arguing for certain things, or often times they have decided that they don’t have to comply or follow a certain thing,” Futurewise’s lobbyist Bryce Yadon said. “This doesn’t change fundamentally how we hold accountability, it just changes who’s the first review of accountability.” Yadon noted that Futurewise, and other citizens and advocacy groups, would still be able to appeal any decision made by the Department of Commerce.

Testimony from local governments against the bill will likely prove persuasive to many legislators, but Rep. Bateman, anticipating pushback from local governments, told the committee to keep the state’s housing crisis in mind when considering the bill.

“This bill is a reflection of the urgency of us to create a new system of accountability to ensure that we’re actually getting the units that we need in Washington State,” she said while introducing her bill ahead of testimony. “While conversations around this bill today… will be centered around technical components of this bill or philosophical beliefs about local control or not, I want to remind us all that this bill is really about people. It’s about people having an opportunity to live in the communities that they grew up in. It’s about people like my little sister having the ability to put down roots start a family. It’s about families spending hours commuting to and from work every single day.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.