As the greenway program turns 12 years old, the network of pedestrian and bike corridors along low-traffic streets could see redoubled commitment or deemphasis.

Jenny Hu lives in North Seattle. As someone who gets around by bike, she regularly uses the city’s network of neighborhood greenways to traverse the city: non-arterial streets intended to be priority corridors for pedestrian and bike travel. 39th Avenue NE, which runs north and south across the Wedgwood neighborhood, is one of those greenways, one she uses to commute to work and do errands. For Hu, using the neighborhood greenway comes with considerable benefits, but also some drawbacks.

“It feels much safer and more relaxing to be separated from car traffic,” Hu told The Urbanist. “I don’t get stuck in traffic jams that form on arterials and it’s just nicer not having to deal with aggressive [or] angry drivers. I am sure every biker has had experiences of getting honked at, yelled at, followed too closely, and passed too closely by drivers on arterials.”

But the downside is that greenway routes often take you out of the way — sometimes into hillier topography to boot.

“The greenways don’t actually connect to any neighborhood amenities,” Hu said. “This neighborhood has nearly all your daily needs within a 1-2 mile radius. However, the grocery stores, post office, coffee shops, restaurants, banks, library, dry cleaners, churches, and synagogues are all on arterials… to actually get to any businesses or gathering spaces, you still have to mix with arterial traffic, which is dangerous.”

Seattle’s greenway network turns 12 years old this year, with the 39th Avenue NE greenway in Wedgwood one of the very first corridors that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) upgraded when it tried out the idea in mid-2012, right after N 43rd and N 44th Streets in Wallingford. At the time, Seattle was following in the footsteps of Portland, Oregon, which officially started branding its bike boulevards “neighborhood greenways” in 2009, but which had been implementing projects like them going back to the 1980s.

As Seattle starts to consider the next iteration of the 2015 Move Seattle levy, which expires at the end of the year, the city has an opportunity to reassess how neighborhood greenway infrastructure has been implemented, and how big of a role the continued expansion of the network should have moving forward. With significant gaps still remaining in the on-street bike network, and many miles of bike lanes still in need of upgrades in the form of physical protection and signal infrastructure, 2024 could be a key decision point.

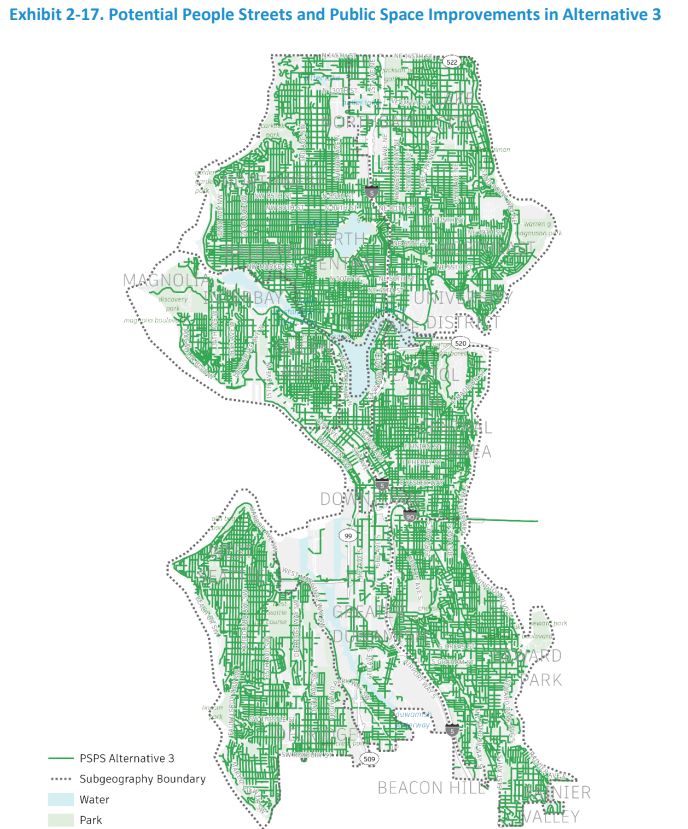

Summer Jawson is the Neighborhood Greenway Program Manager at SDOT, and has shepherded the program since starting in that role in 2015. She’s seen the greenway network go from just over 10 miles long in 2014 to over 40 miles today, getting much closer to the goal of a fully connected network as outlined in the city-council approved 2014 Bicycle Master Plan. That document envisioned neighborhood greenways being the single biggest facility component in Seattle’s bicycle network, comprising 42% of the network compared to 17% in-street protected bike lanes and 13% off-street trails.

That significant expansion of the network almost certainly wouldn’t have happened without the passage of the Move Seattle transportation levy in the fall of 2015, which promised voters that they would see 60 miles of new greenways — a promise that was scaled back during a high-profile “reset” of the entire levy portfolio in 2018 after costs across multiple programs were coming in much higher than expected. Now SDOT is on track to complete around 35 miles of new neighborhood greenways under the levy by the time voters consider the city’s next transportation funding measure.

Jawson described some pushback early in her tenure on the idea of adding bike boulevards to streets through low-density neighborhoods.

“I think some of those early projects, they were neighborhood initiated, but the neighborhoods didn’t know what to expect with them coming in. And it took a lot more work to get people excited about having them as part of their neighborhood,” she said. “But now that they’re such a familiar tool across the city, that people want them in their neighborhood and are really advocating to have them come in. I don’t think we see the kind of resistance to them that maybe earlier stages in the bike program had to go through.”

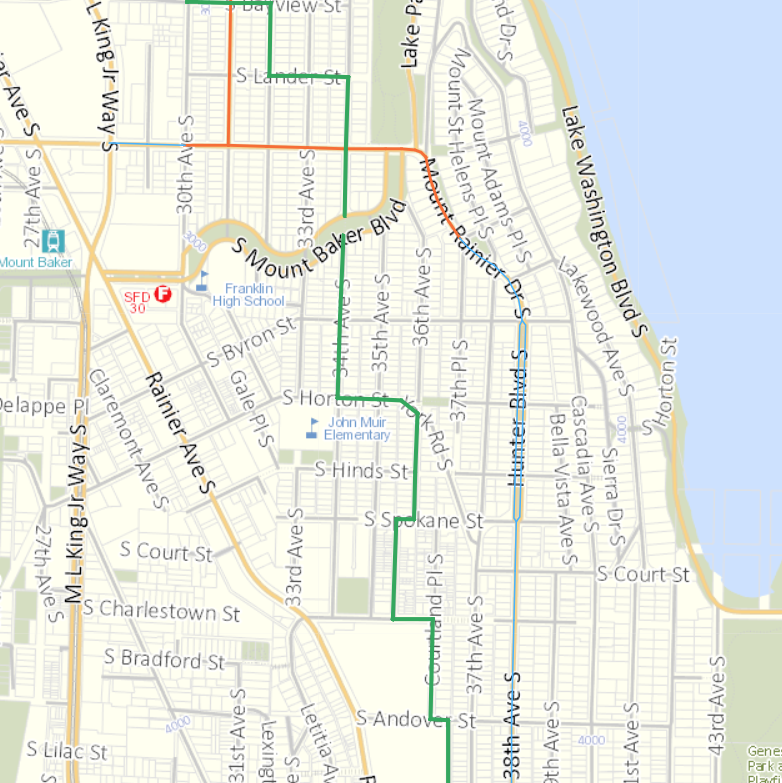

Matthew Snyder lives in the Hillman City neighborhood of the Rainier Valley and uses the north-south greenway in that neighborhood to get around both on foot and by bike. The Rainier Valley Greenway is one of the longest neighborhood greenways in the city, and also one of the most circuitous, zig-zagging through Mount Baker, Columbia City, Othello, and Rainier Beach, and making more than 30 turns along the way. If you aren’t watching for signs or pavement markings, it’s easy to find yourself inadvertently biking off the greenway.

“I find it frustrating at best,” Snyder said. “Where I live, there are very few sidewalks, including on the greenway itself, and there are no diverters or other modal filters to limit cut-through car traffic.”

The Rainier Valley Greenway, which was installed in 2016 when Seattle’s south end had essentially no other protected bike lanes, exemplifies in many people’s minds the idea that greenways are a substitute for on-street bike facilities through areas where the city lacks political will to take away parking of vehicle travel lanes. Rainier Avenue is the most direct route for anyone on bike trying to cut across the neighborhood, but it lacks any dedicated space for bikes.

Snyder thinks there is some very low-hanging fruit that would turn the greenway into a better neighborhood asset. “Every day, I walk on a poorly lit segment of the greenway that has no shoulders and no sidewalks and serves mostly as a cut-through for people avoiding traffic on MLK or Rainier,” he said. “There is absolutely no good reason not to have a diverter here, or failing that, to make traffic 1-way and install a sidewalk, or really to try anything at all, anything other than what SDOT has done, which is nothing.”

Seattle was a trailblazer in the early 1970’s among US cities in the use of traffic diverters, which force drivers to turn and use different streets to cross a neighborhood, discouraging cut-through traffic. But greenways in Seattle have included few new traffic diverters, instead relying on a route selection process that identifies low-traffic neighborhood streets as places to add greenway treatments. But as Seattle continues to grow, and the city continues to right-size arterials streets that are currently overbuilt to improve safety and prioritize transit, cut through traffic will likely increase, especially in areas immediately around urban villages.

Many new diverters are installed directly at spot a neighborhood greenway intersects with an arterial street, allowing people walking and biking to continue across but requiring drivers to make a right turn — a contrast with legacy diverters that were installed in the middle of neighborhoods.

The “Healthy Streets” program, Seattle’s response to the increased demand for street space for pedestrians during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, tries to create an upgraded neighborhood greenway, adding “street closed” signage that allows people to walk and roll in the street when state law would otherwise ban it. But they remain self-enforcing, with little to no repercussions for drivers who choose to ignore signage. And it only takes one driver bearing down on someone trying to enjoy their local Healthy Street to sour someone on using the facility again.

The tension around adding a greenway as an alternative to reallocating space along an arterial street through a business district likely isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. When the Durkan administration was being pressed to cancel fully designed plans for bike facilities along 35th Avenue NE in Wedgwood, the 39th Avenue NE greenway was leveraged significantly by bike lane opponents as evidence that there were existing facilities nearby, despite the significant grade between the two streets. With bike facilities elsewhere scaled back or not considered at all, like on 35th Avenue SW in West Seattle, greenways are essentially the only alternative.

“Because the greenways exist, some drivers believe that cyclists should not be on arterials at all, and they feel entitled to harass you if they find themselves sharing the road with you,” Hu said. “As I’ve noted earlier, all gathering spaces and businesses are still on arterials.”

“I think there’s space for both of them in our system, and they complement each other really well,” Jawson said. “And I think that there’s a need for both the on-street, on arterial bike lanes, protected bike lanes, and the neighborhood greenways. I think we can serve a lot of schools, libraries, community centers, parks with our neighborhood greenway network.”

Jawson pointed to the new protected intersection along Thomas Street, a corridor planned as one of the city’s more urban neighborhood greenways, as elements that hint to the future of the network.

“I think there’s a lot of really great innovative designs that we’ve come up with to include greenways as part of that protected bike lane and off street trail network,” Jawson said. “I’m not looking to replace protected bike lanes with neighborhood greenways.” She noted that many of the planned signature transportation investments envisioned in the Seattle Transportation Plan could build on the current and planned greenway network to provide maximum mobility.

But with limited budgets for bicycle safety and safe routes to school — the two most common sources of neighborhood neighborhood greenway funding — making a clear-eyed assessment of the best places to invest city dollars is essential to achieving the city’s broader transportation goals.

When asked if they support expanding the network or if they prefer shifting the focus of spending elsewhere, the answers from greenway users were mixed.

“I don’t support continued spending on greenways without actual standards in place,” Snyder said, suggesting that the city should be measuring cut-through traffic, vehicle speeds, and lighting levels so people walking and biking can be seen. He also wants to see a separated walking path along every neighborhood greenway, something that would likely be funded via the city’s new sidewalk budget.

“We should really be doing all those things, it shouldn’t be either or,” Hu said. “If I had to choose, I will say it would be nice to have properly implemented bike lanes that actually pass by places people need to go.” She noted that paint-only bike lanes don’t cut it for her, and the city has a lot of miles of door-zone and gutter bike lanes that are in need of upgrading.

An all-of-the-above approach is almost certainly the best way forward, but that doesn’t preclude the city from taking a step back and recalibrating. With the scaling back of Move Seattle’s ambitious goals still leaving a bad taste in many Seattle resident’s mouths, the next transportation levy offers a chance to reset and refocus investments where they’ll have the most impact and improve mobility for the largest number of people.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.