Ambitious development is taking Washington State’s most overlooked city from ‘Vantucky’ backwater to hip.

A few years ago an Urbanist reader approached me at a meetup and offered a story tip. Sleepy Vancouver, Washington on the Columbia River across the stateline from Portland, Oregon, was beginning to wake up.

“You have to check out the waterfront,” he said, explaining that he was certain it was one of the largest and most ambitious urban development projects underway in the Pacific Northwest. I made a mental note about it at the time and put a visit to Vancouver at the top of my project list.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic happened, and my first visit to the ‘Couve’, as I would learn Vancouver is sometimes affectionately called, was set back by a couple years. The long pause may not have been a bad thing, however, as the ensuing months would significantly advance Waterfront Vancouver and other development going on in the city.

By the time I was able to first visit Vancouver in September 2023, only four out of 22 city blocks in the 32-acre project site area remained to be developed. The result was a modern neighborhood of glass and steel towers set on a picturesque seven-acre Waterfront Park on the Columbia River that totally eclipsed the site’s past as a paper mill.

And across the rebuilt train trestle separating Waterfront Vancouver from the city’s historic downtown, growth was evident too. The crowds of people that had been overspilling the area near the public bandstand in Waterfront Park were also making their way to the downtown’s restaurants, bars, and cafés on the pedestrian-friendly streets close to Esther Short Park. As I explored the area, people were eager to talk to me about the changes that had come to the neighborhood. One man who was enjoying a beer with his dog at a sidewalk cafe told me he’d lived in Vancouver his entire life and this summer was the first time he’d seen downtown really come alive.

So a city that a few years ago was just waking up, appeared energized and ready to party by the time of my visit. But what was the story behind Vancouver’s transformation, and what other changes were afoot in Washington State’s fourth largest city? I resolved to find out.

“Van-tucky” Grows Out of Its Nickname

Similar to the rest of Washington State, Vancouver has experienced steady population growth in the last decade. According to data from the U.S. Census, Vancouver surged from about 176,000 to 195,000 residents between 2017 and 2022, a growth rate of 9.4% which made it the fastest growing city in the Pacific Northwest during the five-year period.

The rampant growth brought big changes to a city sometimes nicknamed “Van-tucky” for its sleepy, agricultural feel. When I spoke with Chad Eiken, planning manager for the City of Vancouver, he highlighted that the increase in residents was having a major impact on the look and feel of the city.

“Multifamily residential is really the headline, if you will, of the city’s growth. Commercial is catching up somewhat, but we’ve just seen tremendous multifamily housing development,” Eiken said. “And in fact, we have over 12,000 multifamily units, either under construction or in our development or due to process. And so that is a lot of units that’ll be coming online here anywhere from the next year to the next three years.”

Eiken also cautioned, however, that as in many other Pacific Northwest metros, housing growth is not keeping pace with population growth.

“Even though we’re seeing record levels of development, it’s not making up for an existing deficit in housing, and especially affordable housing that we’ve just seemed to keep, it just seems to keep building that gap,” he said.

In order to catch up, Eiken estimates that Vancouver would need to create about 2,500 units of new housing each year, while currently the city is “averaging anywhere from 1,600 to 2,000 new units a year.”

Current housing prices in Vancouver remain lower than in many Pacific Northwest cities. Data from Redfin estimates that in November 2023, the median home sale price in Vancouver was $460,000, a 2% increase from the previous year. But while prices remain lower than average, so do salaries. The U.S. Census estimates in 2022 that the median household income in Vancouver was about $74,000, significantly lower than the Washington State average of about $90,000.

Despite this, a visit to Vancouver reveals a large increase in housing aimed at the luxury market, and in no place is this more evident than the stunning Waterfront Vancouver project.

Waterfront Vancouver Sets the Bar High

When I spoke with Barry Cain, president of Gramor Development, the firm responsible for the creation of Waterfront Vancouver, he emphasized to me how great an impression the Columbia River site had made on him when he first encountered it decades earlier.

“Living here as long as I have, it was too obvious to me that Downtown Vancouver had a problem. And their problem was they had this paper plant right on the waterfront. So the best piece of property in the city, it had this ugly old big paper plant that had been there for almost 100 years,” Cain said. “If you’d gone to Downtown Vancouver, you would have seen a lot of empty storefronts and stuff like pawn shops and things that go to places that nobody else wants to go to. […] And for the last 20 years, there had been lots of new residential development Downtown Portland, but there hadn’t been anything in Downtown Vancouver.”

Cain saw the acquisition of the paper plant site as an enormous opportunity — so when the company announced its plans to close the plant and sell the land, Gramor Development was among the first bidders and would go on to place the winning bid for the site.

“We felt early on that we wanted to do more than just get rid of a paper plant. We wanted to make this something that told everybody that things had changed direction in downtown and that Vancouver was substantially different from what it had been before. You know, it was pretty normal to hear people talk about Vancouver as ‘Van-tucky’ because it seemed, you know, backward,” he said. “So we felt we had an opportunity. We wanted to make a big difference and set the direction for where things were going — and we wanted to set the bar high.”

Setting the bar high meant engaging in a rigorous planning process for the site and bringing in the right professional talent. As part of the sale agreement, the City of Vancouver had required Gramor Development to build a public trail along the riverfront; however, the team wanted to do more than build a trail, they wanted to build a world-class public space.

After hiring Seattle-based architect David Hansen to do the master plan for the project, they began to make enquiries on which landscape architects to hire and came across PWL Partnership. Based in Vancouver, BC, the firm was known for its work on projects like the masterplan for the iconic Coal Harbor neighborhood in Vancouver, BC, created in the runup to the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, as well as the masterplan for Ship Point Waterfront in Victoria, BC, among many other accomplishments.

PWL’s work on both Coal Harbor and Ship Point Waterfront highlighted how the firm could create vibrant waterfront neighborhoods with a distinctive sense of place rooted in the site’s connection to its surrounding natural environment. To help anchor the vision, one of the PWL staff members recommended that Gramor Development reach out to Larry Kirkland, an internationally acclaimed public artist known for large-scale, multi-dimensional public artworks such as the American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial in Washington, DC.

One of Kirkland’s first suggestions was to change the design of the pier so that it would be suspended over the river using cables, rather than held up by concrete pilings sunken into the water. The mast cable-stayed pier would create a healthier aquatic environment for fish, which Kirkland felt was important to achieving the project’s broader goals since the land had gone through environmental remediation as part of the development process.

“At first I didn’t like the idea because it was going to cost a lot more money and it was going to obstruct the view somewhat, but eventually I came around to it and everybody came around to it and we were really glad we did,” Cain said, noting the mast centerpiece of Grant Street Pier has become one of the most recognized elements of all of Waterfront Vancouver.

Per Kirkland’s suggestion, the design team also incorporated a water feature representing the Columbia River basin and its tributaries. “We liked the water feature right away because it is super educational,” Cain said. “I think that’s really important because, we’re at the most important part of the Columbia River, and most people, including myself, didn’t appreciate it.”

Gramor gifted the water feature to the city, along with the rest of the riverside park. The company also worked with the city to raise $48 million to rebuild a train trestle, a critical infrastructure investment for the future of the waterfront.

The result is a busy, new neighborhood that attracts Portlanders out to visit on evenings and weekends, and which shows no signs of stopping its growth anytime soon — even as Gramor wraps up its project with the construction of an eight-story parking garage with two levels of commercial development and other new buildings on the three remaining blocks.

“It’s projected that we’ll be done in about five years,” Cain said, pointing out that the final three blocks of Waterfront Vancouver would take longer to build than the rest of the project because of space limitations for construction staging. As a whole, however, Cain expressed wonder at how quickly Waterfront Vancouver took off once the plans were fully set in motion, a fact he attributes to the close collaboration between his firm and the city.

“There were a couple people — a mayor and a city manager — who were involved right from the beginning that bought off on it. And they helped to make things happen,” Cain said. “We’ve had three mayors and all three mayors have been really supportive. And that makes a big difference because if you’re fighting with the city over these things, it’s hard to get done.”

But it also should be noted that local politicians have had strong financial reasons to be supportive of the waterfront’s revitalization. An economic impact analysis of Waterfront Vancouver by Johnson Economics estimated that the project has created a $1.5 billion “halo effect” in investment for the city. A prime example is the plan to reimagine the Port of Vancouver’s Terminal One, located nearby Waterfront Vancouver, as a mixed-use development with a year-round farmer’s market. The Johnson Economics report attributed the $350 million in expected construction investment in the Terminal One project to the economic success of Waterfront Vancouver.

Vancouver is Booming Beyond the Waterfront

While Waterfront Vancouver might be in the limelight, many other projects are underway in the city as well, including one which planning manager Eiken believes might be even more consequential for the city’s future development than the waterfront’s revitalization.

The Heights District Masterplan, which recently won a 2023 Governor’s Smart Communities Smart Vision award, envisions creating a new walkable and transit-connected district in the eastside of the city near East Mill Plain Boulevard, an arterial east-west street which will feature one of Vancouver’s two future bus rapid transit projects.

The Heights District will be constructed on and near the location of the former Tower Mall, which encompasses 63 acres that will eventually be the site of 1.58 million square feet in housing, commercial and office spaces, hotel and multipurpose developments, all anchored on a civic plaza, with a festival street and neighborhood park. The project also includes a three-quarter-mile “Grand Loop” that builds connections into the surrounding area. Referred to as “part street and part park,” by the City, the landscaped Grand Loop path will feature outdoor dining, games, seating, and wayfinding elements representing Vancouver’s local culture, history, and natural environment.

Outreach for the Heights District plan has already been ongoing for years with the aim of involving existing community members in the creation of the plan and avoiding displacement as revitalization takes place.

“Some redevelopment activities in the past have done notable harm to particular communities, so part of moving forward in an equitable way is to acknowledge that and understand that we have to do things differently than we’ve done in the past,” said Amy Zoltie, a project manager with the City of Vancouver in a press release.

For the Heights District project, the City will be issuing a request for proposals for the initial city-owned development parcels during the first few months of 2024 with construction on initial infrastructure expected to begin in fall of the year.

2024 will also bring more changes to Downtown Vancouver with the kick off of the City’s Main Street Promise project, which will redesign 10 blocks of Downtown’s Main Street from 5th Street to 15th Street to make them safer and more attractive for pedestrians. Final design plans were approved in November 2023 and construction is expected to begin in spring of 2024.

“We are using some of our federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) money to make some of those improvements,” said Eiken. “We’ve had all this investment in new areas and we also want to show that we value our historic properties and historic Main Street.”

I-5 Widening Marks Crossroads for Livable Downtown

Improving the walkability of downtown Vancouver would certainly be a boon to the many small businesses that have set up shop there in recent years. An eventual light rail connection to Portland, planned as part of the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) megaproject, could also bring many new visitors and residents to the area. However, as Ryan Packer reported for The Urbanist in December, the project alternatives currently under consideration may be as harmful as beneficial to Vancouver’s future as a livable city.

Current plans for the IBR would increase the footprint of I-5 in central Vancouver, with “the base of a new elevated I-5 to tower seven stories over downtown.” Additionally plans for two TriMet Max light rail stations appear to follow design guidelines that prioritize parking and leave stations hemmed in by the freeway and arterial roads feeding it.

Last spring, KGW reported that the City approved the purchase of a 3.2 acre lot adjacent to the public library and I-5 where a future transit mall could be constructed. TriMet Max light rail and Vancouver’s bus rapid transit lines could connect at the site, potentially greatly improving regional transit connectivity. A description of plans for the site, however, also lists parking as a primary amenity.

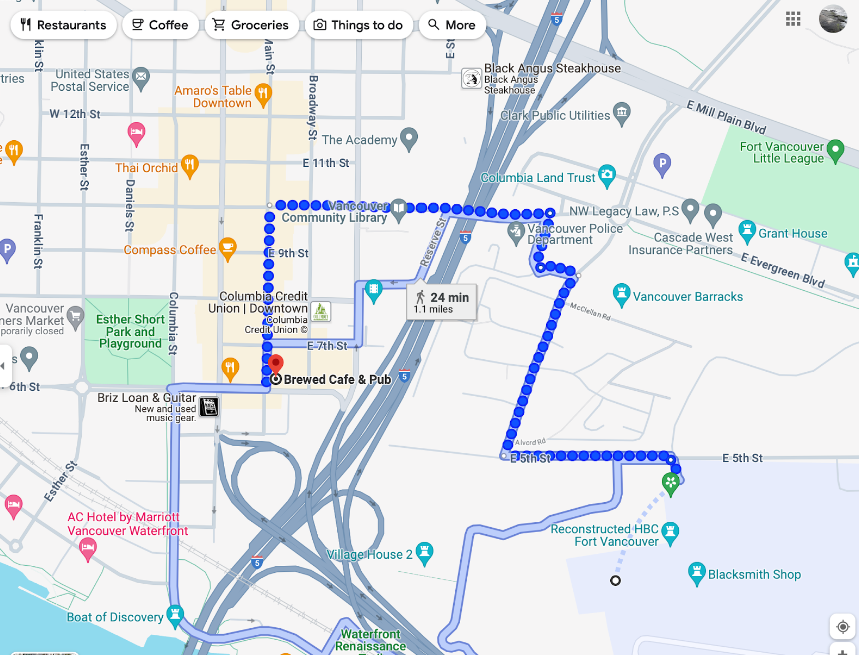

While it may seem logical to construct a park and ride near the interstate, I-5 already brings a lot of vehicle traffic into downtown Vancouver. It also creates a massive barrier between the downtown and the areas of the city to the east, one of which is Fort Vancouver National Historic site. During one of my visits to Vancouver, I had a long conversation with a cyclist about Fort Vancouver and its surrounding parks and trails. He insisted that it was an area of the city not to be missed and gave me detailed instructions on how to get there by foot from downtown. However, because of the length and difficulty of the walk, I was never able to make it across the interstate, which I’m sure is a common situation and results in a sense of disconnection between Vancouver’s east and west sides.

With so much care and attention being paid by the City to improving Vancouver’s livability through urban design, it seems shortsighted for IBR plans to increase the presence of the interstate and car traffic through an urban area with much potential for livable growth.

Thus, while learning about Vancouver, I was able to discover answers to some of my questions about how the city has launched into a rebirth — but I also found questions about where it will be headed in the future. The tension between designing for people and designing for car traffic will definitely be at the forefront of discussions around Vancouver’s future and it will be interesting to see if the level of ambition that has remade the waterfront into a place for people can also be harnessed for the city at-large.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.