While 2023 was dubbed the ‘year of housing,’ 2024 could be a second act, with unfinished business left to tackle.

In 2023, the Washington State Legislature focused its attention on increasing the state’s housing supply with a fervor not seen in decades. And that attention paid off. Laws were passed that will soon require cities across the state to stop banning duplexes, triplexes, townhouses, cottage housing or accessory dwelling units (also known as ADUs) on land zoned for housing. Lawmakers streamlined environmental review for (climate-friendly) urban housing and allowed cities to more quickly remove costly parking minimums. They took steps to limit the impact of predatory delay on new housing when it comes to local design review. They removed red tape around new condominium construction. And they made it easier to add new housing units to existing buildings.

With local governments still trying to get a handle on the full impact of the changes around zoning and permitting laws that the legislature passed earlier this year, many state lawmakers currently getting ready to head back to Olympia to begin the 2024 session want to see this upcoming year turn the “year of housing” into a two-parter. The 60-day session, which starts January 8, doesn’t provide legislators much time to advance their priorities.

Lieutenant Governor Denny Heck, who takes credit for being the first person to call 2023 session the “year of housing,” spent decades working on housing policy reform in both the state legislature and U.S. Congress. He intends to press the issue again in the coming year.

“Our work is not done,” Heck told The Urbanist. “Pretty straightforward: the problem is so big, and some of the solutions that were adopted in [last] year’s legislative session are going to take quite some time to actually be felt on the ground. It’s not a time to let up.”

“I think we’re going to continue to see a significant focus on housing bills, in all of the different realms, including supply, stability, and support — financial investments,” Representative Jessica Bateman (D-22, Olympia), referring to the three priority areas around housing that Democrats in the legislature eyed going into 2023. Bateman spearheaded 2023’s successful missing middle housing bill, which effectively eliminated restrictive single-family zoning in Washington.

“My major message to people is that we have to continue elevating the issue of housing, and not assuming that because we had significant success in the 2023 session,” Bateman said. “We have to continue that success into 2024, make it [Year of] Housing 2.0, and then even continue on during interim of next year.”

Transit-oriented development

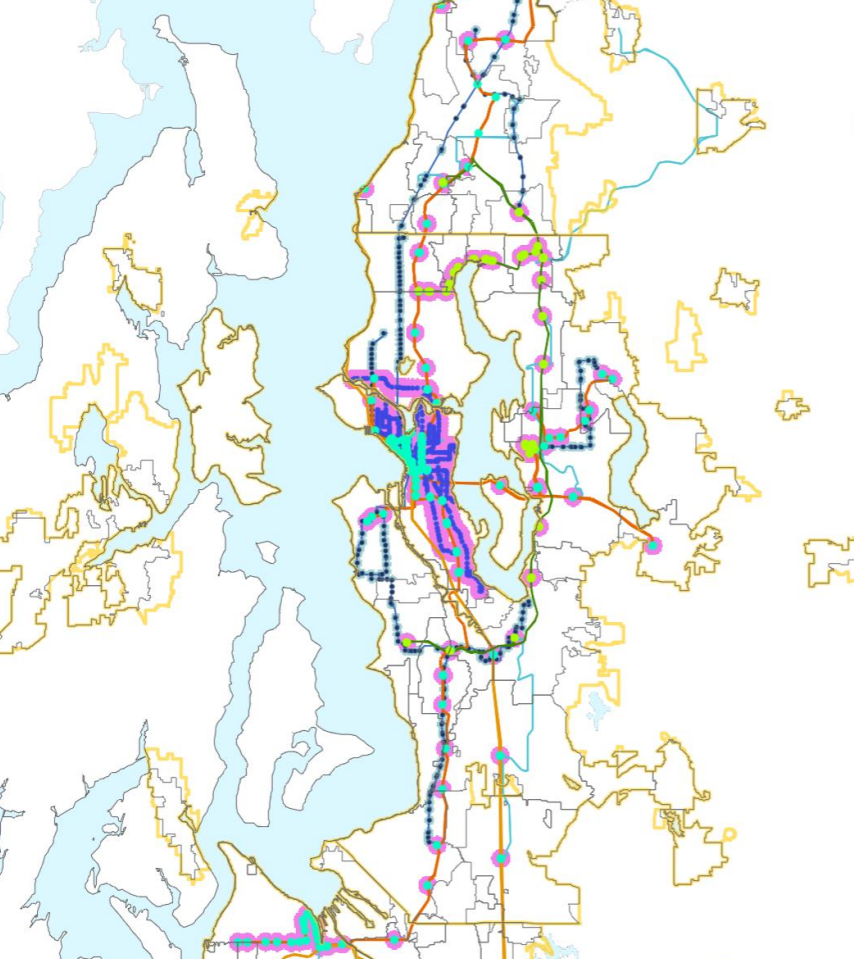

Taking center stage this year will be some major unfinished business from 2023: another attempt at a transit-oriented development bill, requiring cities to open up more areas for development close to the state’s biggest public transit investments. Last year’s attempt, Senate Bill 5466, sponsored by Senator Marko Liias (D-21, Edmonds) and introduced at the request of Governor Jay Inslee, made it out of the Senate but underwent some fairly dramatic changes when it got to the House side, with the clock running out before it could make it to the floor.

In its original form, the bill would have applied very broadly across the state, allowing mid-sized apartment buildings up to three-quarters of a mile from bus stops that see fairly frequent bus service — three buses per hour during most of the day. In areas within a quarter mile of major transit infrastructure like light rail and commuter rail stops, even larger buildings would have been allowed. It provided a maximum amount of flexibility to cities, letting them keep building heights low in some areas as long as they allowed larger ones elsewhere.

Housing advocates see targeted transit-oriented development as an essential piece of the puzzle that’s missing right now. Futurewise, an environmental organization founded in the 1990s to help implement the state’s Growth Management Act, will be leading the effort in 2024 to pass the bill.

“We’ve made a lot of progress on bills last session that allow more types of housing in more places,” Alex Brennan, the executive director of Futurewise, told The Urbanist. “But I think particularly in terms of allowing the type of mid-rise residential and mixed use buildings that are the workhorses of our housing production, that are the types of buildings that our non-profit, affordable housing providers are best setup to use and manage, we really need more of that type of zoning.”

But unlike the Liias bill that would have encouraged development around all transit, as long as it was fairly frequent, we should expect 2024’s TOD bill to only target fixed-route transit like light rail, trolley buses, and commuter rail, as well as “bus rapid transit” (BRT) like King County Metro’s RapidRide lines or Community Transit’s Swift lines. That could have the result of creating an awkward position where the land use around a light rail station that isn’t planned to open until 2044 would be targeted for investments now, but an area with frequent local bus service right now would not.

Another major point of contention is likely going to be the issue of an affordability mandate: a requirement that any developer utilizing the more permissive zoning around transit stations needs to set aside a certain number of units to households making lower-than-average incomes. The bill the senate passed last year didn’t include any affordability mandate, but its chances of getting out of the House without one were slim to none, leading to an impasse.

Taking center stage on the transit-oriented development bill this year will be Senator Yasmin Trudeau (D-27, Tacoma), working with Representative Julia Reed (D-36, Seattle) on the House side. In a conversation with The Urbanist, Trudeau described the affordability mandate as an essential component of any bill.

“I’m very pro supply, and I also recognize that the supply we build is probably going to be catered towards the folks that are making more, because they’ll be able to afford it,” she said. “What I really struggle with is when we’re like, supply supply supply, and not really talking about equitable outcomes in that supply, because to me, yes, it’s about building to where everyone has a home, but I want to make sure that we’re building communities that support one another, that actually learn from one another.” Trudeau said she’s trying shift the terminology away from transit-oriented development and toward “community-oriented development.”

The initial bill is set to require at least 10% of units in new buildings be affordable to households making 60% of the area median income or below — $65,760 for a two-person household in King County. Cities with existing affordability mandates, like Seattle’s mandatory housing affordability (MHA) program, would be allowed to maintain those programs, and cities would be able to add additional affordability requirements on top of the state baseline.

While some housing advocates oppose affordability mandates due to a concern that they will hinder housing growth, Futurewise is on board with the concept of affordability mandate, but they are pushing for flexibility.

“At a high level, a principle that we support is that, as we’re allowing more housing overall, and addressing of our supply needs that way, we want to make sure that affordability for households with fewer resources is is a part of that and that they’re included in the benefits that we’re going to see,” Brennan said. “But we also think that real estate markets vary a lot across the state, and the the difference between the current zoning and the new zoning in these station areas is going to differ a lot across across different station areas. And so we need a program that’s also flexible to address that.”

Rent stabilization

In contrast with the housing supply bills, proposed changes to state law aimed at increasing stability and enhancing protections for current and future rental tenants didn’t get much traction at all in 2023. A bill limiting rent increases that exceed inflation to 3% per year, and prohibiting landlords from charging move-in fees or deposits that exceed one month’s rent, had 29 co-sponsors in the House, with 11 co-sponsors signed onto a similar bill in the Senate, but neither bill was able to get to the floor of either chamber. That was also true for a House bill requiring six-months notice for rent increases over 5%, requirements similar to those currently in place in a number of major cities in the state.

One major factor in their lack of success seems to be the fact that none of those bills had any Republican co-sponsors. Despite Democrats retaining majorities in both the House and Senate, that lack of support from across the aisle often grinds things to a halt, when a relatively small number of Democrats are able to ensure something doesn’t move forward.

“I would say it’s a difficult topic even inside my own [Democratic] caucus,” Senator Trudeau said. Trudeau sponsored the senate’s version of last year’s rent stabilization bill, and wants to see a similar measure return. “I say this with all due respect to my colleagues, we don’t have a lot of renters in the legislature. So it also means that we don’t have a lot of perspective of what the rental market is right now.”

Cities across the state are continuing to beef up their rental protection ordinances, but statewide reforms would be able to create a new floor of protections that would ensure no one slips through the cracks, and would make things much easier to understand for landlords and tenants alike compared to the piecemeal system that’s in place now.

Trudeau sees a rent stabilization bill as an essential element in addressing the state’s homelessness crisis. “I hope that my colleagues, in the organizing around this, can really see what we’re experiencing, [and] really dig into the data, which shows a pretty strong correlation between the increase in rent and the number of people that are pushed onto the street,” Trudeau said.

The state legislation passed a rent control ban in 1981. In the intervening years, housing prices have spiked and homelessness has remained a persistent issue, with some local jurisdictions like Seattle asking the state to repeal the ban so they can stabilize rents.

Dedicated revenue for housing

The third area of priority for housing is set to be the amount of state investments in affordable housing. In just Central Puget Sound, out of the projected 810,000 new units of housing needed to accommodate population growth by 2050, at least 34% of new units will require some level of public subsidy, according to data produced by the Puget Sound Regional Council.

In the state’s capital budget for 2023-2025, the legislature allocated $400 million dollars to Washington’s housing trust fund, the largest amount ever. Ultimately, this was a step back from the move that Governor Inslee wanted to see the legislature take, which was to issue state bonds to be able to fund ten times that amount over a longer time frame, to sustain the investment needed in housing affordable to low-income people across the state. Some lawmakers want to see a more dedicated source of revenue.

A bill introduced by Rep. Frank Chopp (D-43, Seattle) in 2023 would have added a new threshold for the state’s real estate excise tax (REET) that would apply to any property sold for more than $5 million dollars, taxing everything above that amount at 4%. The revenue would be split between the state’s housing trust fund, and other state funds that invest in types of affordable housing, including a new Developmental Disabilities Trust Account.

The bill also lets cities add on an additional 0.25% REET to fund affordable housing at the local level, with counties able to “take over” collection if a city within the county decides not to collect the additional revenue. According to a fiscal analysis, Chopp’s bill would have generated over $400 million per year for the state by the end of the decade, and over $250 million for local governments, filling in a substantial part of the gap needed to meet projected housing needs for subsidized housing. Expect this discussion to continue into 2024.

Legalizing “co-living” housing

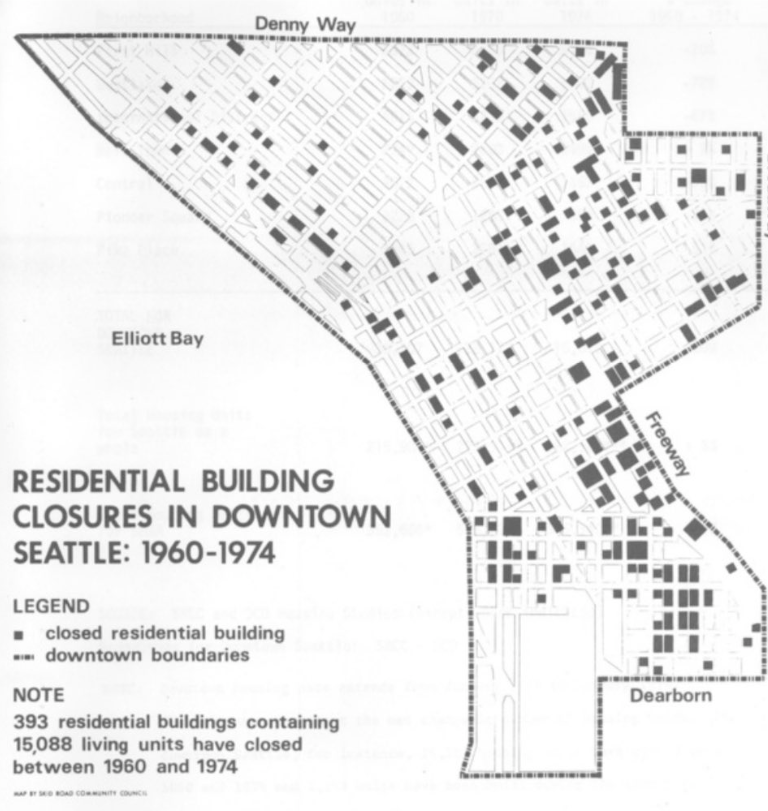

A new proposal likely to generate a lot of attention this session would re-legalize single room occupancy (SRO) buildings, rebranded as “co-living housing.” SROs are buildings with individual units for sleeping quarters, but with shared kitchen and food preparation areas, shared bathrooms, or both. Providing a way to offer low-income housing without public subsidy, SROs were widely seen in US cities at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, but were banned in many places by the 1980s.

In Seattle, following high profile fires at two downtown SRO buildings in the early 1970’s, the city council passed what were known as the known as the Ozark Hotel Ordinances, which effectively forced dozens of residential apartment buildings to close after building owners weren’t able to pay the significant upgrade costs needed to comply with the new building code.

Today’s SRO buildings look very different from the ones built 100 years ago, and are exemplified by the “Apodment” buildings that dot Seattle’s landscape. Most of the ones in place today were built in the late 2000’s and early 2010’s, before public opposition to so-called “Eastern Bloc” style housing led to the city council to increase regulations on microhousing, effectively killing them.

With a House version sponsored by Representatives Mia Gregerson (D-33, Burien) and Andrew Barkis (D-2, Olympia) already introduced as HB 1998, and a Senate counterpart quick on its heels sponsored by Senators Jesse Salomon (D-32, Shoreline) and Chris Gildon (R-2, Olympia) as SB 5901, the fact that the idea has bipartisan support is likely to move it along, but introducing a new proposal like this in a short session is usually intended to test the waters and gain feedback from legislators, and not try and cross the finish line in one go.

The bill as introduced would require all Washington cities to allow co-living housing in all multifamily zones, and ban them from being able to impose unit size restrictions that are more onerous than the state building code currently in place. Parking requirements would be banned within a half mile of a major transit stop, and are capped at one stall for every four units outside of those areas.

Despite the fact that current fire codes look very different today than they did during the 1970’s, expect the argument that microunits are unsafe to feature prominently in the debate around this pair of bills. “It’s worth remembering that the SROs of yore aged into poorly maintained fire traps. Today’s developers should heed history. Build, and maintain, for the future, not just the present,” The Seattle Times editorial board wrote in an op-ed in 2013 asking the city council to ban them.

But with a broad array of supporters behind the idea of re-legalizing co-living housing, ranging from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), to the League of Women Voters and the American Farmland Trust, in addition to pro-housing stalwarts like the Housing Development Consortium, the idea looks to have considerable momentum.

Pushback from local governments expected

On top of a short window to pass bills, lawmakers will also be hearing “slow down” from a powerful constituency: local elected officials. With cities and counties in Central Puget Sound all under a time crunch to update their local comprehensive plans by the end of 2024, there will also be a push from city councilmembers and county commissioners to hold off on making any more changes to local land use and zoning codes. Some localities that had been caught flat-footed by last year’s housing push have regrouped and are focusing their lobbying efforts on trying to ensure that bills passed in 2024 don’t significantly add to their workloads.

“We’ve given an extension in legislation for cities: they have six months until after they’ve passed their comp plans for their codes to reflect those new changes that we’re requiring of them. And if they don’t make those changes, we have model codes that the [Commerce] department is currently working on,” Rep. Bateman said. “As much as we can work together with cities, we also have to be thinking about these state level policy actions, and sometimes that creates a conflict with their timelines or what resources they think they have to address those solutions.”

Lieutenant Governor Heck also cited those concerns as understandable but that they aren’t the primary concern of the legislature. “It takes a while for the snake to digest the dog, as it were,” he said. “But on the other hand, I think more cogently, when you’re at this much of a housing deficit in this serious of a crisis, we can’t sit still. So, I understand that they need to go through this process, and I understand it’s a cumbersome, time intensive, sometimes complex process. But look, we’re going backwards. So we can’t wait. We just cannot afford to wait.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.