Barreling toward a boondoggle? Money piles up for freeway project, but key questions remain unanswered.

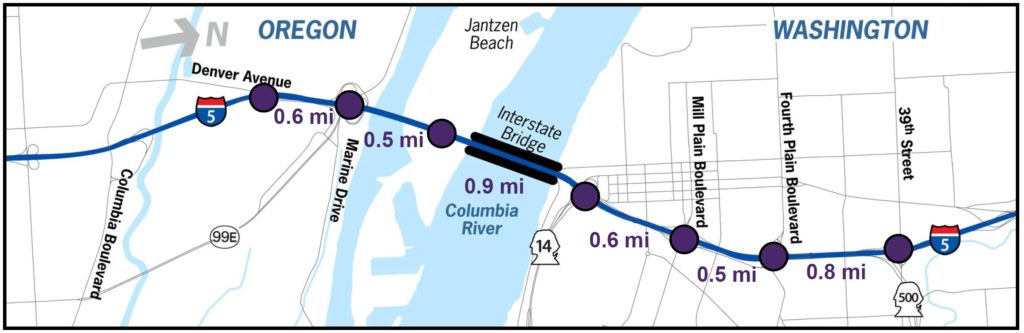

Late last week, three members of Washington’s congressional delegation announced a $600 million grant that will fund the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) project, a five-mile expansion of Interstate 5 that includes replacing the two aging highway bridges over the main navigation channel of the Columbia River. The grant, awarded via the National Infrastructure Project Assistance program — also dubbed the Mega Grant program — is one of the largest single grant awards ever seen in either state, but is just a small piece of the overall funding needed to complete the project, expected to cost between $5.5 billion and $7.5 billion dollars at last estimate.

The $600 million in funding joins $1 billion that has been earmarked for the project by both Washington, within 2022’s Move Ahead Washington transportation package, and Oregon, allocated during the 2023 legislative session. The IBR is ultimately banking on the receipt of an additional $1.9 billion in federal dollars, including $1 billion in Federal Transit Administration (FTA) funding for the planned extension of TriMet’s MAX Yellow Line north across the state border, another one of the IBR’s components.

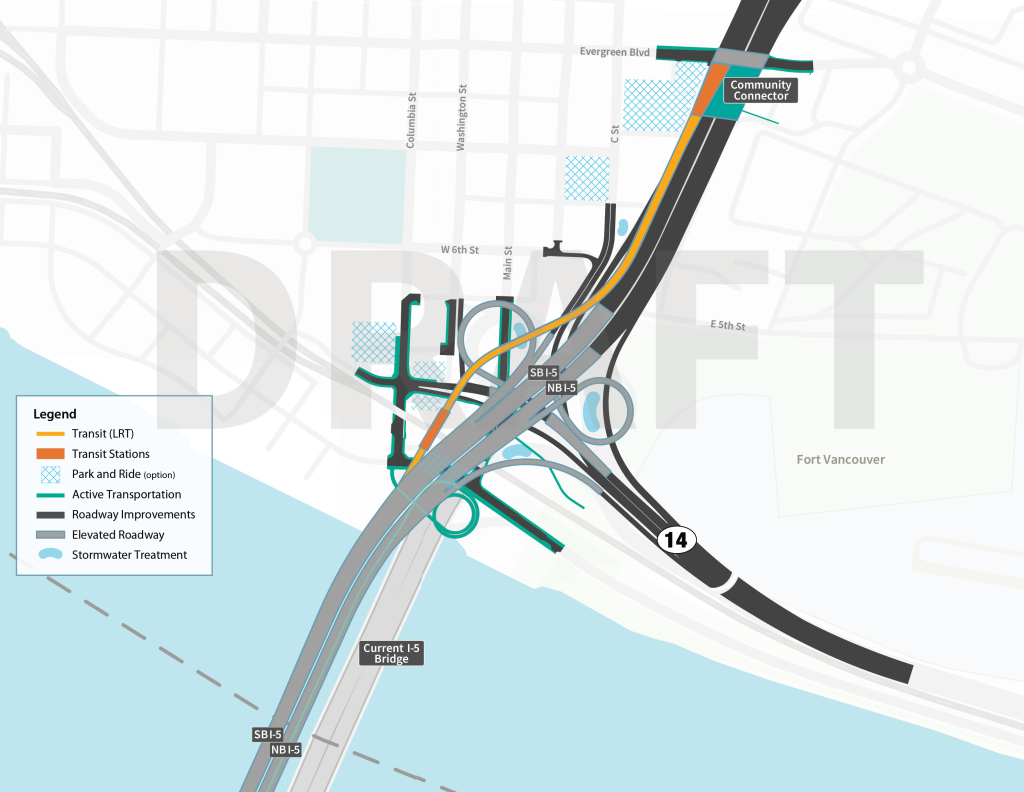

The highway project’s impacts on Vancouver, Washington’s fourth largest city, and northern Portland have taken a backseat as design on the entire project has advanced in recent years, as project boosters continued to tout the need to seismically upgrade the twin river crossings. But the options under consideration call for the base of a new elevated I-5 to tower seven stories over downtown Vancouver, creating the type of urban barrier that many US cities are trying to undo this century. Most of the renderings released by the IBR program have shied away from showing the expected impacts on the cityscape, instead opting to show bird’s eye views from single perspectives, usually focused on the river crossings.

Earlier this month, Washington Governor Jay Inslee visited the I-5 bridges, touting the need to move ahead on a replacement. But the project moving forward includes a much broader scope than the simple replacement of those aging river crossings, a holdover from the failed previous attempt at bridge replacement and freeway widening that had been called the Columbia River Crossing (CRC). Seven interchanges would be replaced as I-5 is expanded to 10 lanes along the project length, with the added “auxiliary lanes” touted by the project team as not adding any additional traffic capacity while at the same time relieving congestion, reducing trip times on the corridor.

Though the CRC went into dormancy in 2013, the IBR is utilizing the official Record of Decision (ROD) approved that year as part of its current plans, electing not to update the official purpose and need to include considerations that are recognized as more urgent now, like climate change and equity. Alternatives that were briefly reviewed, like an immersed tunnel, were discarded because they don’t provide the same connectivity to all of the existing I-5 ramps.

Taking a broader look at the project and modifying the CRC’s purpose and need would likely have added years to the IBR’s timeline, delaying the initial construction start date of 2025 that has likely already slipped to 2026. A draft supplemental environmental impact statement — which supplements the 2013 documentation from the CRC with updated designs — had originally been set to be released this fall but has been delayed to next spring. With the release of that document, Washingtonians and Oregonians will get the clearest look yet at the IBR and what its impacts are likely to be.

Oregon Governor Tina Kotek, who shelved a plan to add an additional lane to I-205 earlier this year following pushback on tolling plans for the corridor needed to finance it, is also all-in on the IBR.

“This is a big moment for the Pacific Northwest and demonstrates the national significance of this effort,” Kotek said in a statement. “This project will help advance our goal of reducing emissions through a modern, multimodal bridge and will provide an infusion of federal funds to our region that will support local jobs and broader workforce opportunities.”

Senator Maria Cantwell, in making the announcement Friday along with Senator Patty Murray and Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, noted that the Mega Grant program, funded by 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, had been specifically designed by her office for projects like this one: incredibly expensive megaprojects that most state transportation budgets can’t handle.

“I was proud to author the Mega Grant Program to help us tackle transportation projects that drive the economies of entire regions, but are too large and complex for one community or state to fund alone,” Cantwell said in a statement. “By upgrading and adding lane capacity, we are enabling more regional economic growth and better day-to-day travel experiences for commuters.”

Cantwell referenced another megaproject on a state border that has received Mega Grant funding: the Brent Spence Bridge between Kentucky and Ohio, a $3.6 billion new highway that’s widely recognized as one that will increase traffic into the Cincinnati metro area and exacerbate, rather than relieve, the public health issues that come with highways. The U.S. Public Interest Research Group earlier this year included the Brent Spence Bridge on its list of highway boondoggles that will “do little to reduce congestion or address real transportation challenges, while diverting scarce funding from infrastructure repairs and key transportation priorities,” along with… the Interstate Bridge Replacement.

In touting the project’s bona fides around climate, IBR staff have promoted the light rail component and a planned shared-use path that will upgrade the existing narrow sidewalk alongside the I-5 bridge, and the fact that these two elements make up a sizable share of the total project cost. But the three planned MAX stations — one on Portland’s Hayden Island and two in Vancouver — won’t be designed to maximize ridership and are essentially add-ons to the highway expansion project, with the barrier of the highway itself limiting the potential gains from light rail.

Project planners are still exploring whether to utilize land nearby for one or two park-and-ride lots, an approach that Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) Secretary Roger Millar has questioned as outdated. The inclusion of light rail stirred up opposition to the previous CRC iteration, particularly among conservatives, which, along with cost concerns, doomed the project. State leaders are hoping this time around is different.

As WSDOT tries to shift the top priority for the state’s transportation investments toward maintaining existing infrastructure — and improving that infrastructure in a way that reduces serious injuries and fatalities — the IBR stands as an example of the old way of doing business. Yet there appears to be little political appetite to divert from the course that’s been laid so far, in which the Columbia River Crossing’s assumptions and scope all get carried forward into the IBR, with the result the single most expensive highway project that either Washington or Oregon has ever seen.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.