JCTP is Bremerton’s 30-year transportation vision. It gets a lot of things right, but has some gaps.

The Joint Compatibility Transportation Plan (JCTP) is a transportation collaboration between the City and the Naval Base Kitsap (NBK, aka ‘the shipyard’). The shipyard’s location was chosen precisely because it’s hard to reach and thus protected from enemy attack. But the topography that makes it hard to reach for enemy ships also makes it hard to reach for the shipyard’s 22,000 employees (set to grow substantially this decade).

The JCTP is largely (90%) funded by the Department of Defense’s Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation (LDCC), whose mission is to “support the readiness and resiliency of military installations and defense communities.” The US Navy supported the study but was not actually part of the committee, due to limits on how military branches can interact with local governments.

The 100-page JCTP Final Report (with an additional 400-page appendix) compiles information from 19 previous Bremerton studies across an array of growth-related issues: traffic, active transportation, parking, housing, land use and more. The report includes a summary of traffic and transportation conditions, and projects future conditions for 2050. Finally, the report provides recommendations to solve future transportation planning issues.

Big growth on the little peninsula

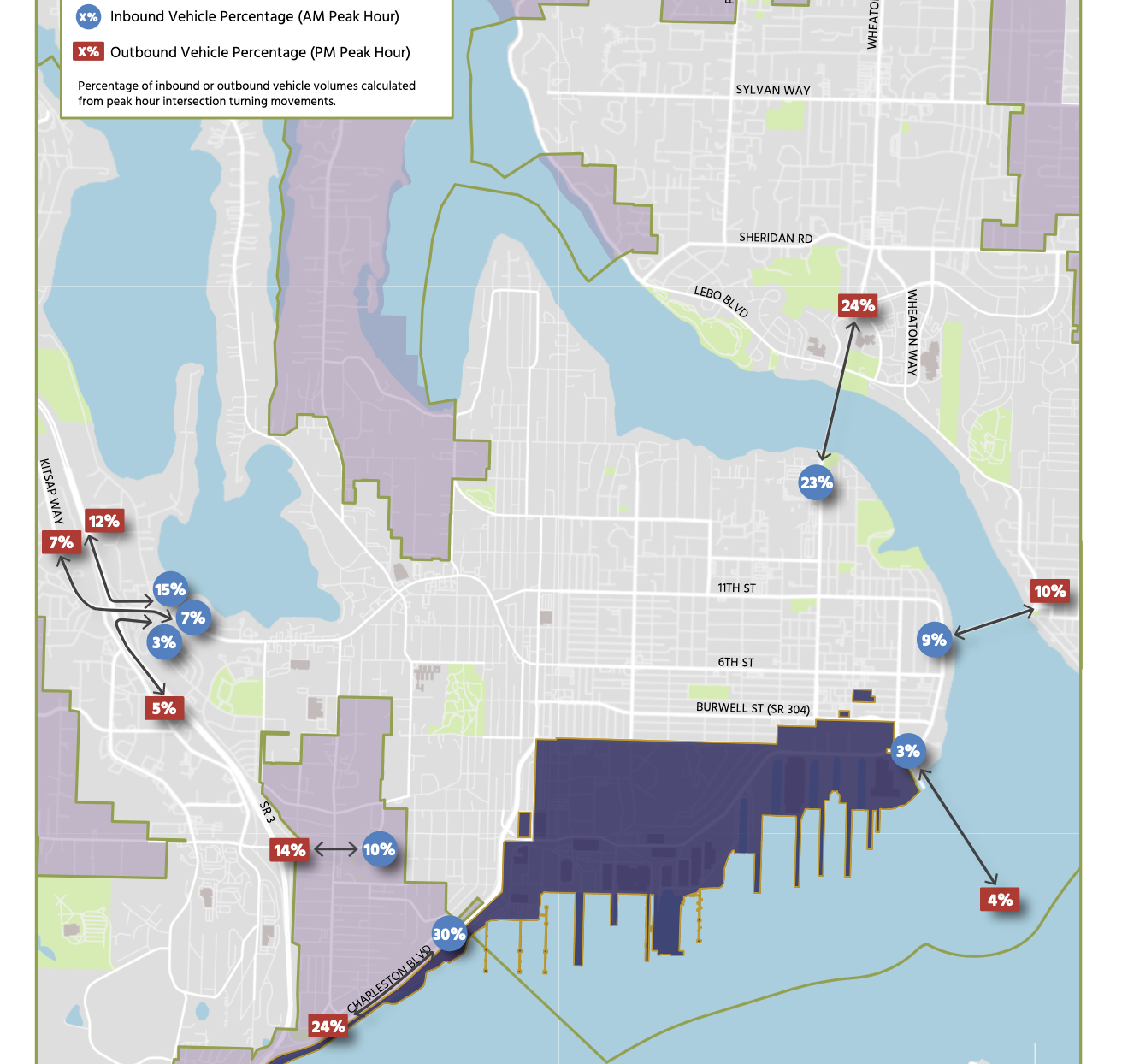

Bremerton’s JCTP Study specifically addresses the commutes of civilian employees and sailors currently employed at Naval Base Kitsap (NBK), which the US Navy considers a national security priority. Currently, about 22,500 (numbers fluctuate) work at the shipyard, but 5,000 additional workers will arrive this decade as the naval base undergoes a major expansion, including construction of the world’s largest dry dock.

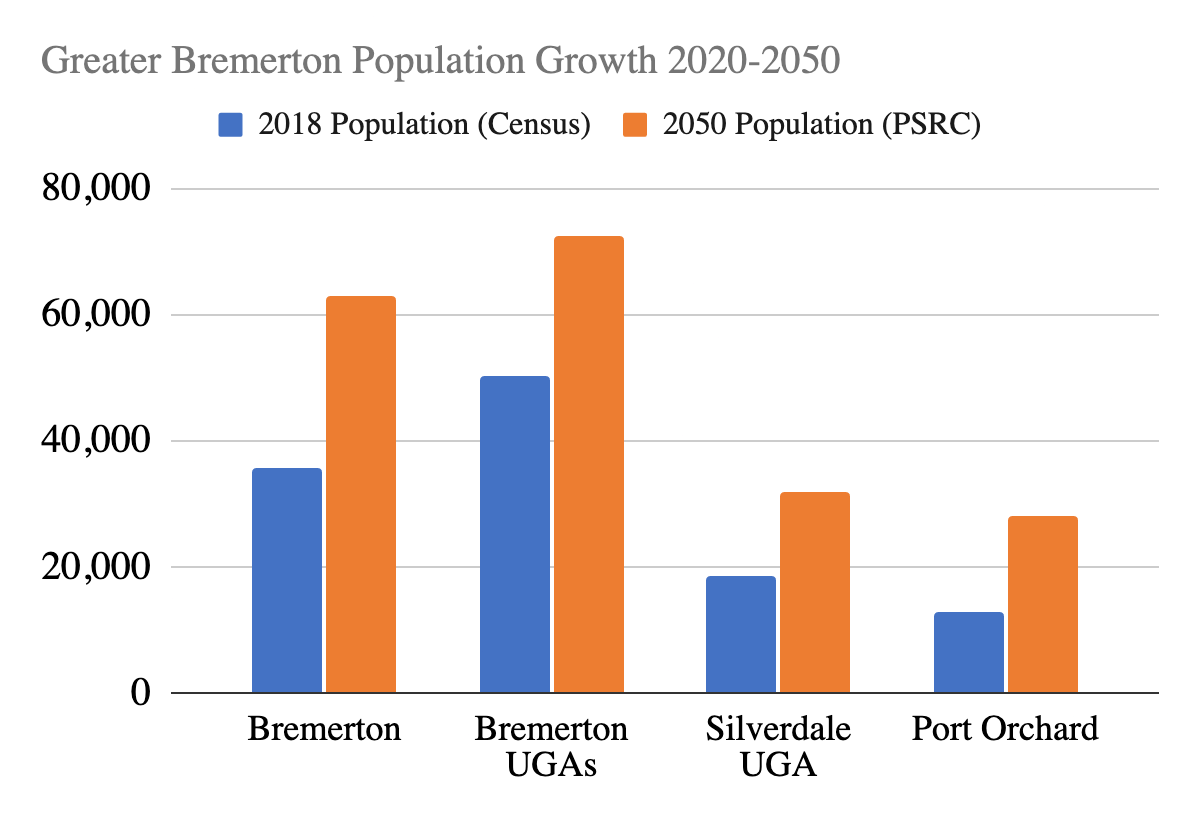

The JCTP Report assumes high growth population and employment growth. The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) predicts that the City of Bremerton will grow 77%, a faster rate than Tacoma (69%) or Seattle (40%). Greater Bremerton (Bremerton, Port Orchard, Silverdale and the unincorporated communities around them) will add 78,000 residents and grow to 195,000, according to projections. Additionally, employment in downtown Bremerton (principally Naval Base Kitsap) will see high employment growth, bringing 55,000 workers downtown every day (14,000 more than today).

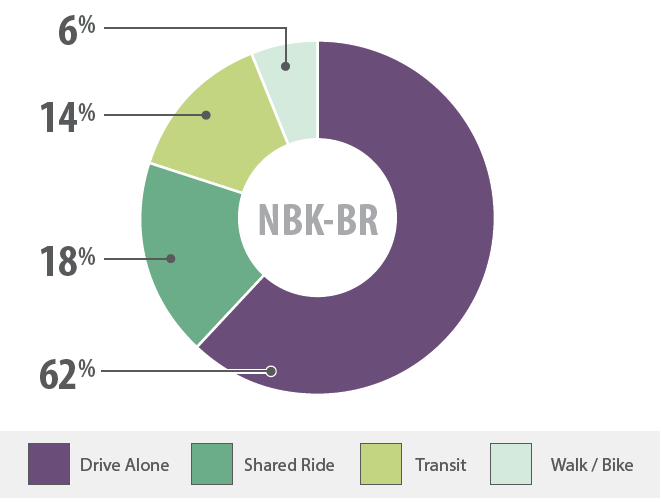

Currently, 18,600 (80%) of NBK-BR workers either walk to work, drive solo or carpool in a private car. If the additional 5,000 workers drive at the same rate, 3,500 new commuters would need to find a place to park and otherwise clog the streets of Central Bremerton. Central Bremerton is a small, densely packed peninsula surrounded on three sides by Puget Sound.

The report frames upcoming transportation decisions with a powerful either/or: Do we want a ‘Livability Centered Vision’ with fewer cars and more transit/bike lanes? Or do we want a ‘Capacity Center Vision’ with wider streets and more cars. (Spoiler: they pick Livability!) In other words, should the City and region build transportation networks that prioritize the health and safety of people who live here (including the ongoing influx) over the needs of those who drive into the city for work.

Two bad alternatives, one good one

The JCTP Study proposes three strategies to manage growth-oriented transportation. Unfortunately, the three alternatives have rather bland, parking-focused names. The report was written by engineers, not marketing pros, so I’ll forgive it.

- ‘Support parking alternative’ – More parking in City of Bremerton and expand roadways

- ‘Add base parking alternative’ – More parking on NBK and expand roadways

- ‘Relocate parking alternative’ – Increase transit, active transportation and housing close to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, increase transit from park-and-rides.

‘Support’ and ‘Add base’ alternatives were rejected because “large road capacity projects are costly, disruptive, and will require more right-of-way. Additionally, roadway capacity projects can be hard to fund and may be infeasible due to environmental constraints. Parking constraints under a capacity-centered vision will remain and may worsen as growth increases density in downtown Bremerton,” as the JCTP noted in section 7-2.

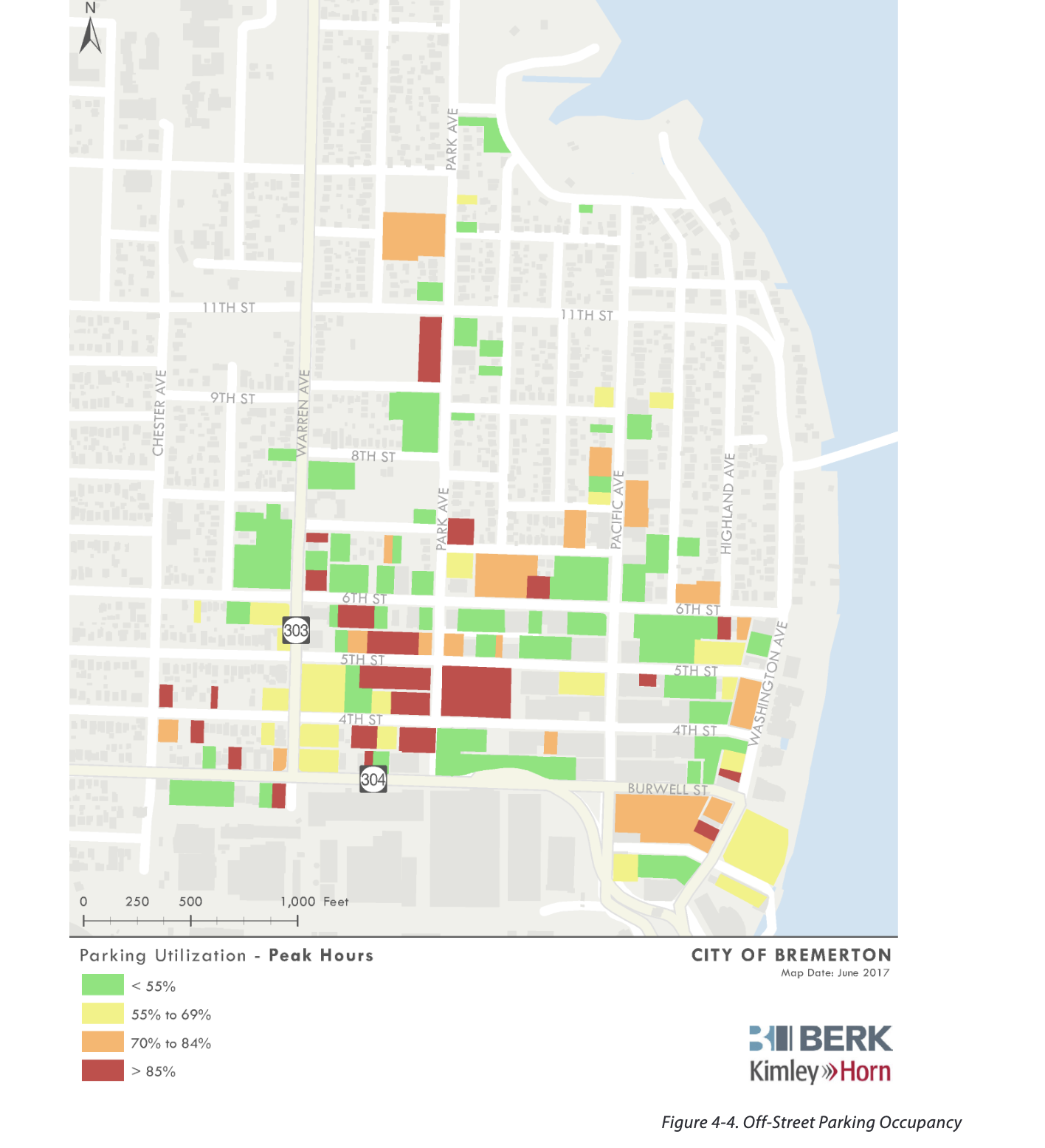

The Shipyard has explicitly rejected the ‘Add base parking’, both because there is no space at NBK, and “building more structured parking on NBK-BR will be difficult due to Department of Defense (DOD) funding constraints.” The base already has about 8,600 parking stalls and a federal government-owned 960-stall structure in downtown Bremerton. The message is clear, the Navy isn’t going to accommodate thousands of additional cars inside the tight confines of Naval Base Kitsap.

So, why not build lots of new parking with new, multi-story parking lots downtown? What would 5,000 new parking spots cost? A December 2023 study in nearby Poulsbo estimated a 100-stall lot would cost up to $15 million, or $150,000 per stall. Three multi-story lots in South King County will “add somewhere around 1,500 new parking spaces, penciling out to more than $200,000 each.” Assuming the lower Poulsbo rate, 5,000 new parking spots would cost $750M. And many millions more would be needed for widening inbound highways and streets, a challenging proposition amongst Bremerton’s narrow, hilly topography.

To absorb tens of thousands of new residents without adding vast new car infrastructure, the City needs a different plan. With courage and foresightedness, both the City of Bremerton and the Shipyard have decided to place the needs of its people before the needs of cars.

The Preferred Alternative

Instead, the JCTP’s Preferred Alternative was called ‘Relocate Parking.’ Great efforts will be made to increase the number of NBK and ferry commuters that arrive without cars. “Benefits of a livability-centered vision include improved walking and bicycling experiences, reduced commuter parking in neighborhoods, increased available parking for businesses, a greater likelihood of achieving mode shift goals that thereby reduce congestion and improve travel times, and finally, consistency with City plans to increase density downtown and improve economic vitality,” the JCTP states. That’s exactly the right alternative, for the right reasons.

The JCTP’s preferred alternative introduced ‘themes’ that should guide future infrastructure improvement projects. These are absolutely the right themes, and they are notable for their complete absence of additional car capacity.

- Reduce car trips downtown by building active transportation projects, improving transit capacity and reliability, employer incentives, etc.

- Reduce NBK-BR commuter parking in downtown and adjacent neighborhoods. Add parking in strategic locations outside downtown.

- Several car-focused initiatives like NBK Gate expansion for inbound cars, 560 new parking stalls in park-and-rides and so-called ‘adaptive signaling’.

Adaptive signals are controversial because when they’re designed poorly, like in Seattle’s very dense South Lake Union, it’s quite bad for pedestrians, who have to wait longer to get a green light as the system pumps more cars through. Nonetheless, the report calls for adaptive signals for Bremerton’s Wheaton (SR 303) and Kitsap Way (SR 310). In theory, adaptive signal technology could benefit pedestrians if paired with pedestrian-centric elements like ‘leading pedestrian intervals,’ new stop lights for mid-block crossings, and meaningful traffic calming at intersections. The devil will be in the details.

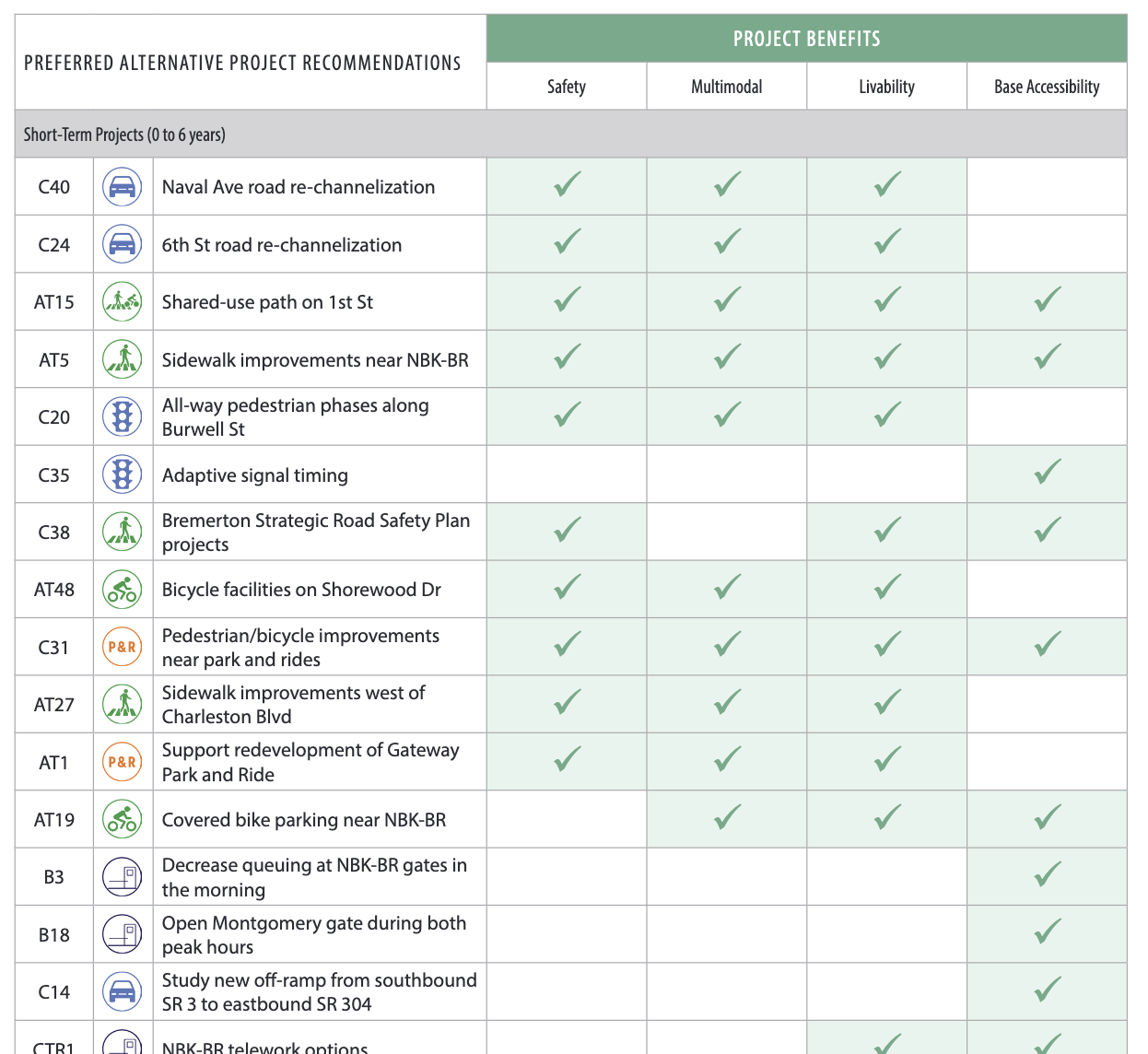

Next, the JCTP study contains a very long list of infrastructure projects, ranked according to cost and difficulty. Happily, the majority of the highest scoring projects are focused on transit, safe walking and the bike network. Caveats abound: Not every project listed has equal merit, much less funding — a fancy study isn’t the same as a new sidewalk, etc. But there’s no question that the Preferred Alternative is well-aligned with the high-ranking future infrastructure projects — and all that stuff will improve ‘livability’ in Bremerton.

Five quibbles

The JCTP is an enlightened transportation document, but it’s only a transportation document. The upcoming 2024 Comprehensive Plan should build upon the JCTP and consider these additional transportation-adjacent ideas.

- The JCTP prioritized projects to get shipyard workers to Central Bremerton, which is great, but that focus risks ignoring outlying neighborhoods like western Sheridan Park and West Hills. The tide must lift all boats.

- The JCTP doesn’t set specific goals for increasing the percentage of people who get around Bremerton on bus/ferry, bike and foot. The 2024 Comp Plan should.

- Bremerton must incentivize multi-family housing near the base as a traffic mitigation strategy. Incentivize this housing by reducing or eliminating parking minimums, reducing the time required to secure housing permits and density-favoring impact fees, like per-acre rather than per-unit.

- The outlying neighborhoods will never be served if Bremerton doesn’t learn how to build low-cost bike/pedestrian infrastructure within its own transportation budget. Mere paint and plastic bollards can make an intersection safer or inspire a neighborhood’s bike commuters. Build first, then study, change as needed. Be bold, Bremerton.

- The JCTP doesn’t even name Kitsap County as a partner, probably because traditionally, it hasn’t been one. But the three-member Kitsap County Board has two new commissioners and a new administrator. Perhaps the County will start contributing positively to Bremerton’s efforts to expand multi-modal transportation.

But quibbles aside, Bremerton’s JCTP study gets a lot more right than it gets wrong. In fact, the plan may be the boldest transportation vision of any city on the Puget Sound, actively restricting additional traffic growth, firmly rejecting large new parking lots and reducing car lanes on two major streets in central Bremerton. There’s a long way to go as the City is essentially starting from scratch — there are zero dedicated bus lanes and only two blocks of protected bike lanes in the entire city.

The JCTP is a bold plan with much to admire. Time will tell if Bremerton can follow through. Comments can be sent to City.Council@ci.bremerton.wa.us.