With maintenance base costs rising as much as $1 billion, Tacoma Dome Link could be at risk of further delay.

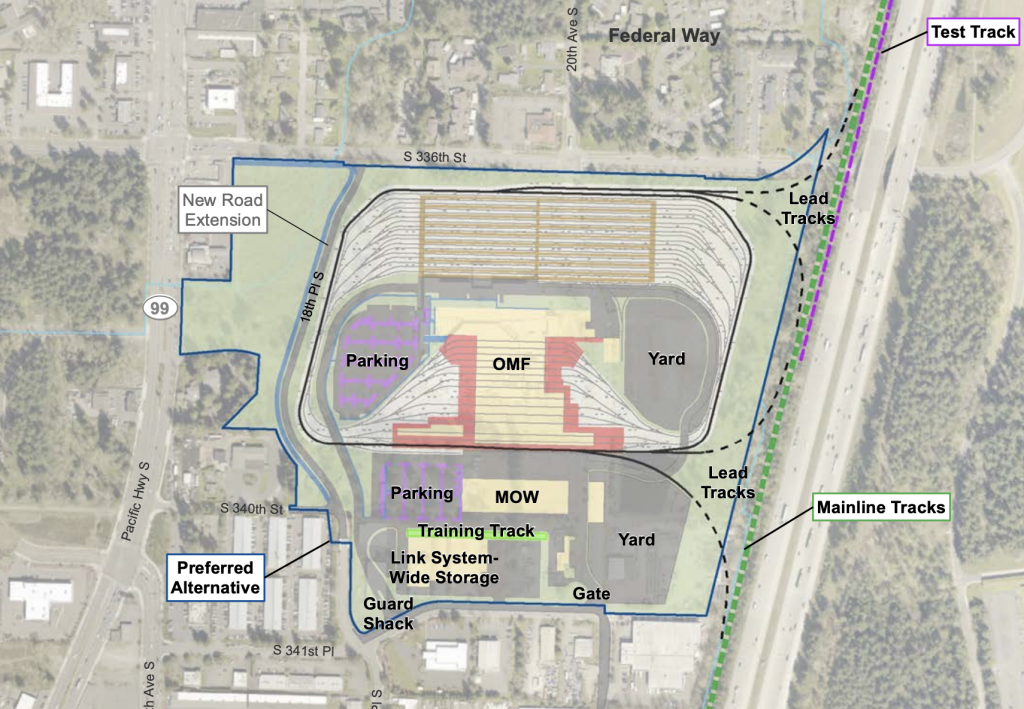

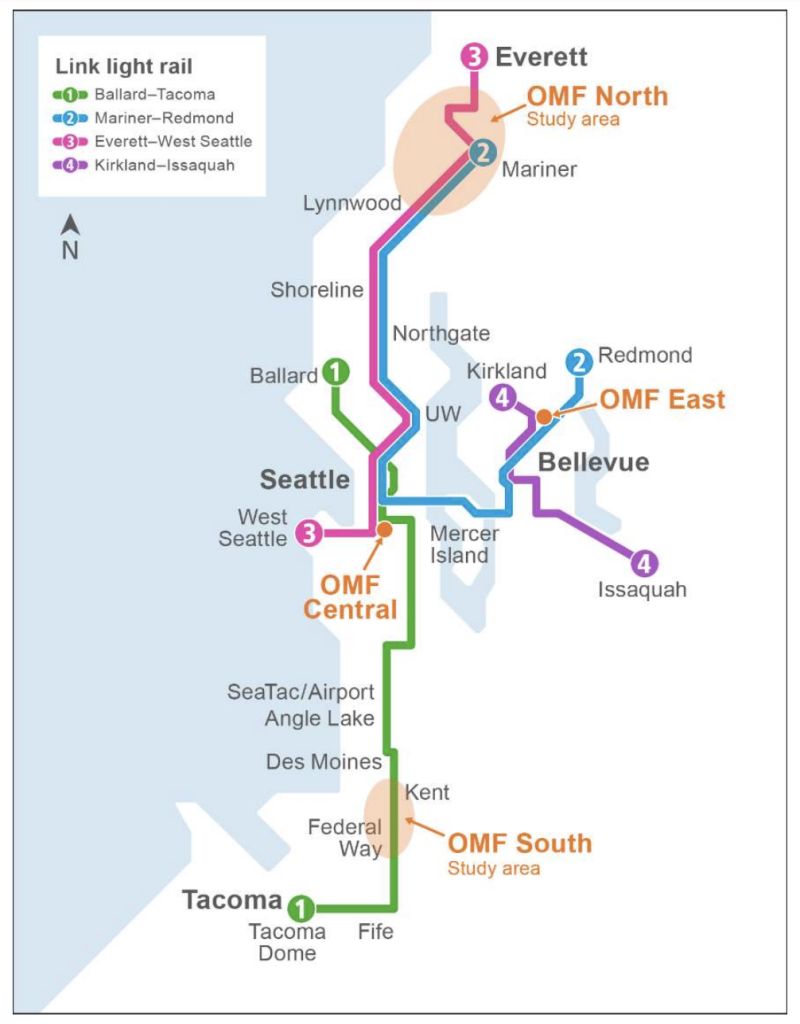

Sound Transit has unearthed meteoric cost increases for the agency’s Operations and Maintenance Facility (OMF) South in Federal Way. Agency staff shared the news on Thursday at a committee meeting, blaming the cost increases primarily on inflated market conditions and a new cost-estimating methodology.

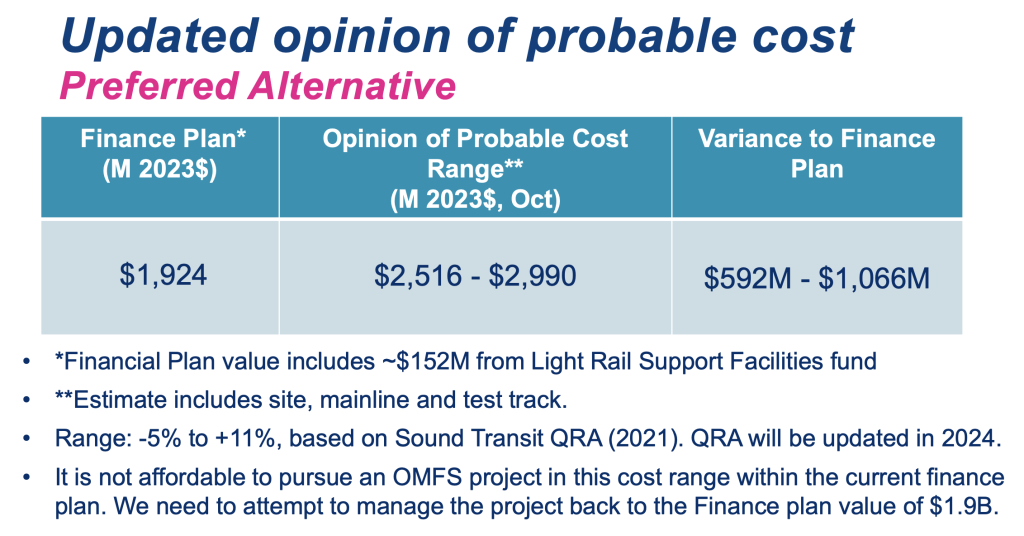

Cost estimates for OMF South are about $592 million to $1.066 billion more than assumed in Sound Transit’s realigned financial plan, placing the project in the range of about $2.5 billion to $3 billion. If the agency can’t find savings to bring the project closer to $1.9 billion, it could spell further delay to project opening, which is risking a slip from 2029 to 2032. It could have knock-on effects, too, that further delay opening of the Tacoma Dome Link Extension now likely to open in 2035 instead of 2032 due to its own project challenges.

Last week, agency planner Curvie Hawkins, Jr. detailed where the OMF South project cost increases are coming from.

“Many of the cost drivers of the increases are similar to recent expenses with other major Sound Transit projects and WSDOT projects as well,” Hawkins said. “Across the region, the hot construction market combined with inflation are generating an escalation in materials costs — this accounts for about 23% of our increases.”

“Additionally, there are work scope changes to address Sound Transit operational needs as well as permit requirements for the City of Federal Way and other agencies — this accounts for about 20% of our increase,” Hawkins added. “And then there were overall market condition adjustments that we addressed as well which have resulted in about 25% of our increase in cost.”

The original estimate used as a part of the early environmental review process was based upon a “unit cost library” cost-estimating methodology. Now that the project is moving toward a preliminary engineering phase, the agency is using a more rigorous and in-depth “bottoms-up” methodology.

Don Billen, the agency’s planning director, said that the unit cost library approach essentially considers typical costs for similar project items. So if a project involves building tracks, the methodology looks at how much track is needed and uses a per foot cost estimate approach. The unit cost library methodology, however, is not keeping up with changing market conditions in the post-pandemic era, missing some significant swings in construction costs.

“So when we went from this high-level unit cost library estimating to the bottoms-up estimating, the estimators are now trying to capture that current construction market,” Billen said. “And so you’re seeing that reflected here. There were some changes in scope as well that contributed, but the largest factor appears to be the construction market and the change in estimating that.”

Nevertheless, Sound Transit staff said that they were trying to bring project costs closer to affordable levels around $1.9 billion, as anticipated in the agency’s long-term financial plan. Two strategies are being employed to do this: optimizing project scope and utilizing a design-build procurement process.

In terms of project scope, agency staff have so far identified about $200 million in project savings that they say would have minimal impact. Those project savings, however, may come at the cost of additional light rail vehicle (LRV) storage that the agency needs to attain planned Link service levels under the current operating plan — Sound Transit estimates that it needs an extra 90 LRVs systemwide to reach service level goals and thus extra storage space.

Next year, Sound Transit plans to issue a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) in hopes of finding firms interested in managing a design-build contract for OMF South. The goal of the RFQ would be that firms propose bids at more affordable levels. Through the design-build process, a chosen firm would be responsible for designing a project that fits the project scope but engineering designs that come with deeper savings. Agency planners also hope that a design-build contract could include the potential for additional LRV storage capacity, if eventually deemed necessary.

Tracy Reed, an agency planning manager, tried to explain how the RFQ and Request for Proposals (RFP) processes could work favorably with the design-build approach.

“The proposal here is to allow enough time to really do more design development and drive down the kind of costs that are carried for risk allowances thereafter by collaboratively working with the top ranked firms during that RFP development phase,” Reed said. “So there are a number of different aspects to our proposed design-build advertisement that we think will help to achieve these goals.”

Claudia Balducci, the System Expansion Committee Chair and a King County Councilmember, asked in response if the RFQ to be published would include the “affordable” project price at $1.9 billion. Reed essentially said it would, minus a few items like project administration and right-of-way acquisition costs.

Reed also explained that just because cost estimates appeared higher than the agency’s maximum affordable price, Sound Transit could still include an additional scope of work to be evaluated as part of the project. That extra scope would be above the minimum project scope and bidders could respond to say if that work is still affordable or not within the maximum affordable price for the project.

“It’s a strategy we’ve used, for example, on the recent design-build advertisements for the Sounder program,” Reed said. “And it’s been actually quite successful in those projects to see how the market responds and what they can deliver above and beyond the minimum scope that we require.”

Whether or not this design-build approach will really work from a cost savings standpoint for a project of this magnitude, however, remains to be seen. Typically, the design-build project delivery method has the benefit of reducing project risks and change orders during construction. That can save money and re-engineering work, particularly during the construction phase, but the design-build approach doesn’t inherently mean that total project costs are significantly less — or less at all — than they would be with a design-bid-build project delivery approach. Closing a delta of $592 million to $1.066 billion in project cost overages seems a big hope just by using a different project delivery method and scope optimization while still wanting add-ons.

Adding to Sound Transit’s mounting troubles, too, are light rail vehicle (LRV) costs. While the agency board just signaled its support for 10 extra Series 2 LRVs to be delivered this decade, costs for those vehicles are assumed to be considerably higher than other Series 2 LRVs in the procurement pipeline from the same manufacturer. Dave Peters, the board’s independent consultant, raised the concern earlier this month that the LRV Series 3 procurement — set to reach about 100 LRVs — in the 2030s could be much higher than the $2 billion Sound Transit has budgeted for it right now.

Suffice it to say, the tea leaves strongly suggest that costs for Sound Transit 3 are set to keep ballooning, one project at a time, risking delivery timelines and viability of the entire program.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.