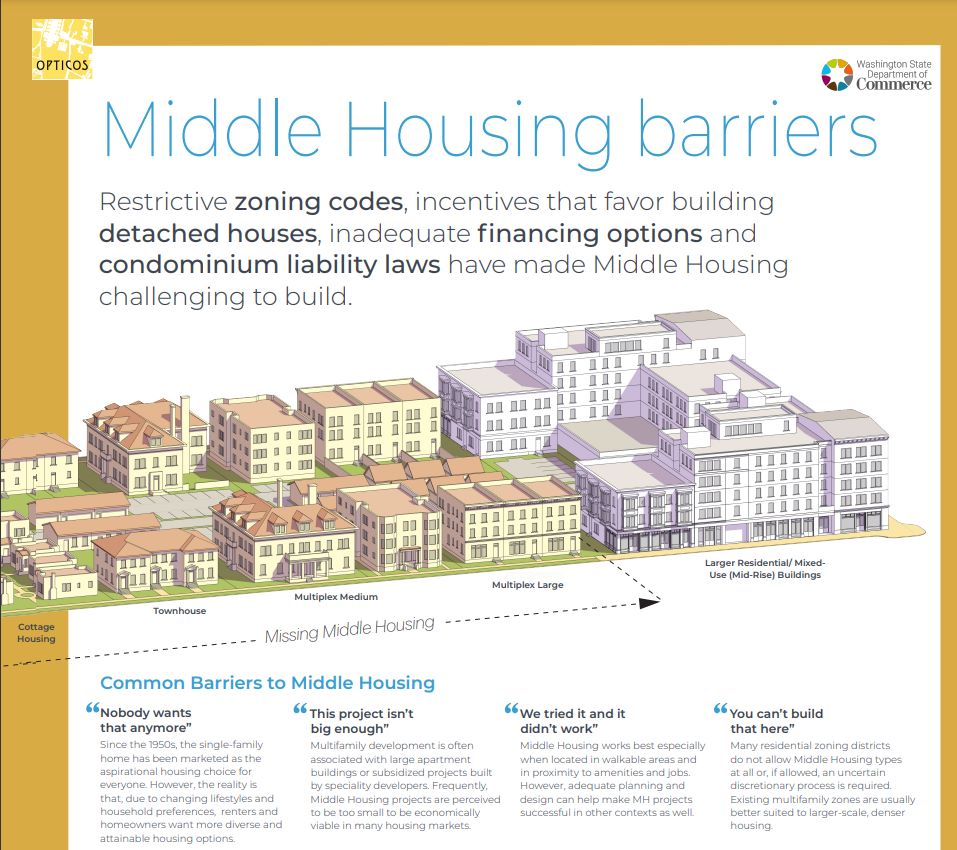

The Washington State Department of Commerce has released draft guidance and model codes to implement the state’s a new middle housing law. The new law will apply to most cities with a population of at least 25,000 residents (and some smaller cities), requiring them to broadly legalize middle housing throughout residential zones. Cities in King, Pierce, Snohomish, and Kitsap Counties will need to be fully compliant with the law by July 2025.

A key piece of the new middle housing law empowers the state via Commerce to issue model codes. These codes can be foisted upon any city failing to comply with the law. It’s a backstop to ensure that the law cannot be skirted around by local communities refusing to adopt their own version of the law. The model codes also offers a yardstick and an easier path for other cities to incorporate the law directly into their zoning codes without too much work. Cities, however, will have to decide if they want to create a zoning overlay, amend existing zones, or establish entirely new zones to implement the law.

The law establishes three tiers of cities, with Tier 1 cities having the highest level of middle housing requirements. Tier 1 cities are defined as having a population of at least 75,000 residents while Tier 2 cities have a population of at least 25,000 residents but less than 75,000 residents, and Tier 3 cities have a population of less than 25,000 residents but are located in a county with a population of at least 275,000 residents and are situated in a contiguous urban growth area with the largest city in the county — such as the smaller suburbs of Seattle within King County.

The model codes set a floor for local ordinances

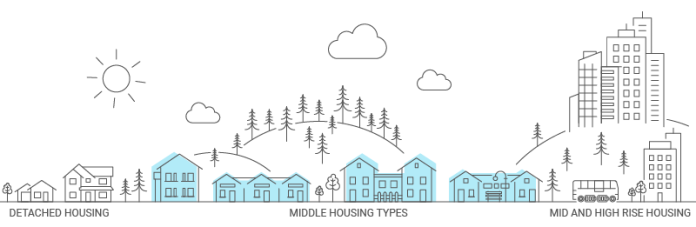

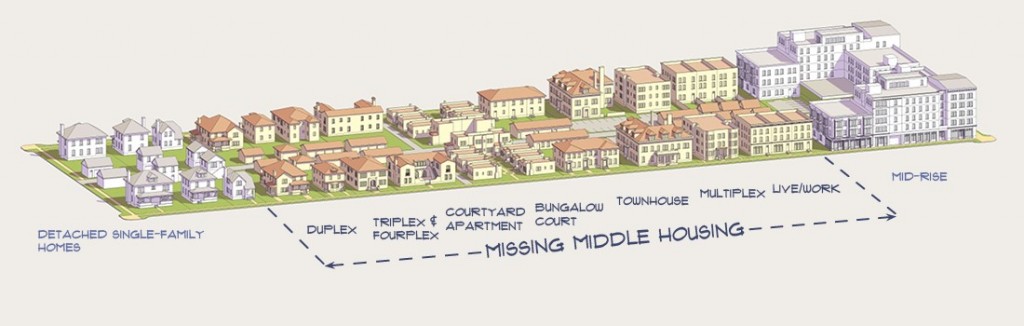

Generally speaking, the model codes closely follow the letter of the missing middle housing law with a few additions and clarifications. Highlights of the model code are summarized in the following table:

| Standard | Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Housing Types | At least 6 of 9 types of middle housing1 | Same as Tier 1 | At least 4 of 9 types of middle housing1 |

| Base Density | 4 homes per lot2 | 2 homes per lot2 | 2 homes per lot |

| Density Bonus | 6 homes per lot when near major transit or 2 homes are affordable2 | 4 homes per lot when near major transit or 1 home is affordable2 | N/A |

| Floor Area Ratio (FAR) Limit Minimums | 2 homes: 0.6 FAR 3 or 4 homes: 0.8 FAR 5 or more homes: 1.0 FAR | Same as Tier 1 | N/A |

| Lot Coverage Limit Minimums | 5 or more homes: 50% 4 or fewer homes: 40% | Same as Tier 1 | 40% |

| Setback Maximums | Street or front: 15 feet, except 10 feet for lots with 3 or more homes and 20 feet for garage doors Side street: 5 feet, except 0 feet for attached homes Side interior: 5 feet, except 0 feet for attached homes Rear: 15 feet, except 10 feet for lots with 3 or more homes and 5 feet along alleys Exceptions for projections: 5 feet into front and rear setbacks for covered porches and entries, and 3 feet into front and rear setbacks for balconies and bay windows | Same as Tier 1 | Street or front: 20 feet Side street: 5 feet Side interior: 5 feet, except 0 feet for attached homes Rear: 20 feet, except 5 feet along alleys Exceptions for projections: 5 feet into front and rear setbacks for covered porches and entries, and 3 feet into front and rear setbacks for balconies and bay windows |

| Height Limit Minimums | 35 feet | Same as Tier 1 | Same as Tier 1 |

2. The density requirements don’t apply to lots after subdivision below 1,000 square feet unless the city has a law allowing lot sizes below 1,000 square feet.

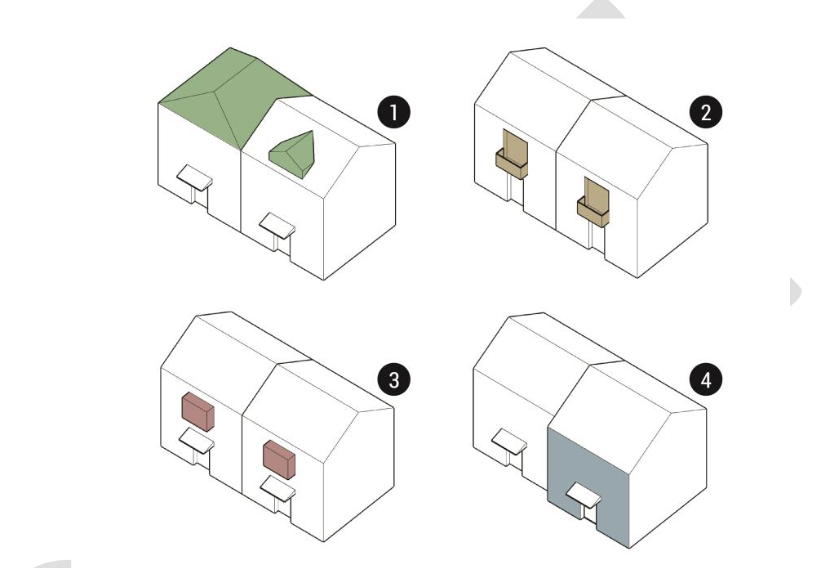

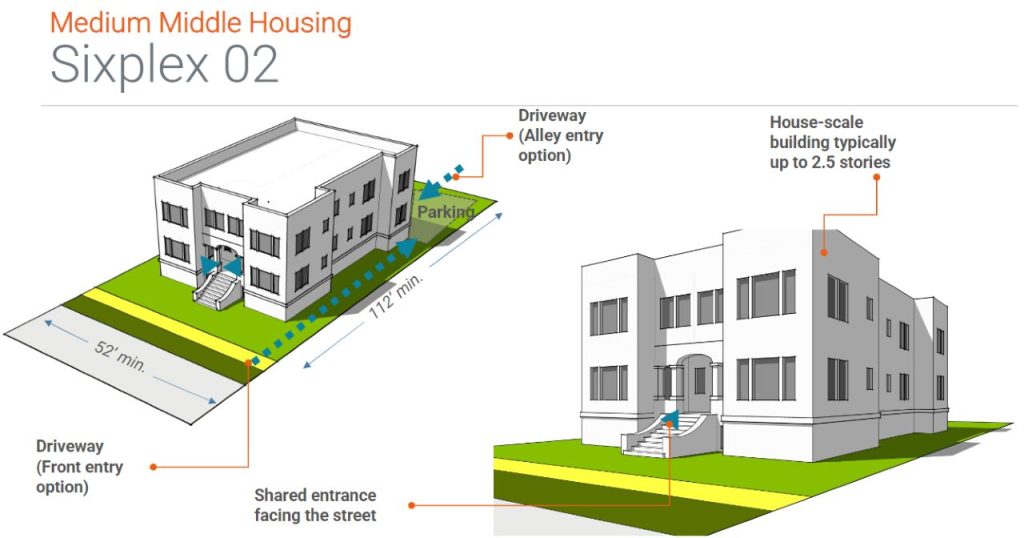

The model codes also contain design standards that apply to middle housing, except for small conversions of existing structures to middle housing. The design standards are focused on having prominent building or unit entries with weather protection as well as windows and doors on street-facing facades reaching 15% coverage. Design standards also call for pedestrian access to sidewalks, de-emphasizing garages, and articulation strategies for attached homes (e.g., roofline changes or dormers, balconies, bay windows, or offset facades).

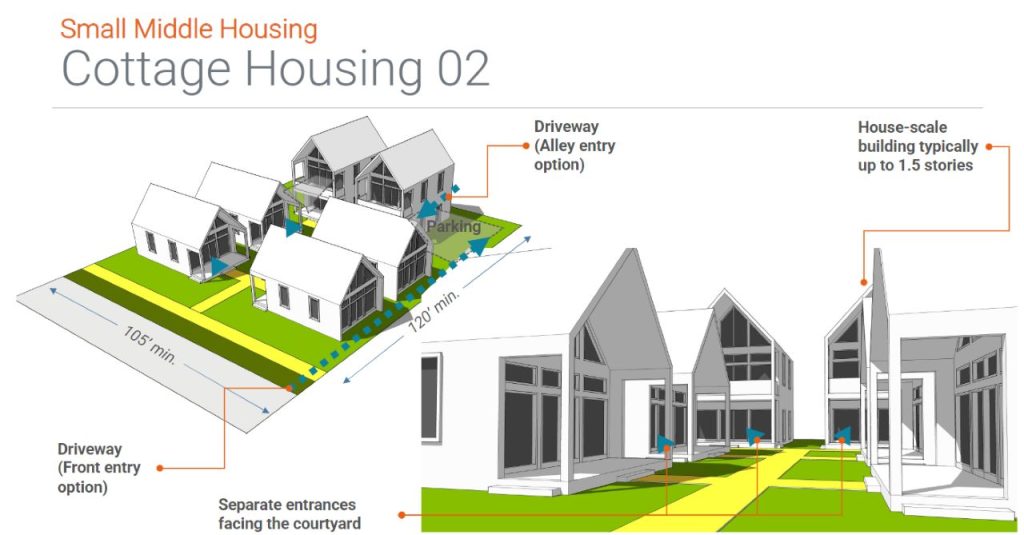

Design standards go deeper to define cottage housing, courtyard apartments, and tree regulations. Cottage housing units would need to be 1,600 square feet or smaller (not including attached garages), have defined entries, and share common open space upon which units border. Courtyard apartments are similar in that they’d need to have a common open space and generally border it with pedestrian entries facing the common open space or a street. As for trees, the design standards acknowledge that tree requirements cannot be more restrictive than tree standards for single-family detached residences, except that the model code would allow for a modest amount of required trees in cottage housing and courtyard apartment developments for common open spaces.

When the new middle housing law is implemented in cities, a corresponding law on design review will also come into force. That law will limit the type of design review cities can have. Only administrative design review processes can be applied to middle housing projects, except in cases where middle housing is in a locally designated historic district or affects a landmark.

As far as vehicular access and street improvements, the model codes limit what cities can ask for. Frontage improvements and driveway requirements, for instance, generally can’t be more burdensome than what is required for single-family detached residences. The only exception to this is specific standards laid out in the model code. Most of those requirements are common for multi-unit developments and not particularly burdensome.

Commerces offers deeper guidance and policy choices to consider

In the guidance document, Commerce generally says that cities can go beyond the minimum requirements of the middle housing law with flexibility. Throughout the document, Commerce highlights local policy choices that cities should consider in adopting middle housing regulations.

One key recommendation is expanding the major transit stop density allowances. The middle housing law requires cities apply a higher density allowance at least a quarter-mile from a major transit stops, but the guidance suggests expanding this to a half-mile. Expanding the distance would be consistent with provisions eliminating off-street parking within a half-mile of a major transit stop. The guidance also explicitly suggests “permitting transit-oriented densities, multifamily housing, and a variety of non-residential uses.” A major transit stop, by the way, is defined as any stop serving rail transit (i.e., light rail, commuter rail, streetcar, and monorail), aerial gondola, bus rapid transit, trolleybuses, or any other transit funded and expanded by Sound Transit.

A second key recommendation is to exempt middle housing from car parking mandates. Commerce goes to great length to illustrate the high cost of car parking and the counterproductive nature of car parking to urban environments. At the very least, Commerce suggests fully eliminating car parking mandates for new middle housing, conversions of structures to middle housing, and affordable housing everywhere. Another suggestion is to allow on-street parking to count toward off-street parking requirements.

A third set of key recommendations is around bulk regulation flexibility. To allow for a little more building height reaching toward four stories, the guidance suggests that cities allow a five-foot height limit bonus for pitched roofs. Other bulk regulations like setbacks, floor area ratio, and lot coverage should be less stringent, the guidance says, to support more density, design options, and less costly housing types.

Some other recommendations include:

- Using specific exemptions under the State Environmental Policy Act to increase building capacity. Several statutory laws and administrative rules are cited as examples to accomplish this.

- Offering density bonuses for cottage housing. Commerce says that cottaging housing units should only be counted as half a unit when calculating density limits, essentially offering a two-for-one bonus.

- Increasing the number of lots that can be approved through a short subdivision, a streamlined lot creation method. State law requires that cities allow at least four lots in a short subdivision, but cities can authorize short subdivision approval process to permit up to nine lots. The middle housing law technically requires Tier 1 cities to allow for short subdivision of six lots. Commerce further recommends streamlining preliminary review and final subdivision (plat) processes as provided for in state law.

- Allowing larger missing middle housing, that is between seven and 20 units like courtyard apartments, in areas “near transit, commercial services and job centers, and other amenities.” The guidance also suggests consideration of point access block (single-stair) structures as contemplated in Senate Bill 5491.

- Allowing middle housing on regulated critical areas in the same way as other development. The middle housing law exempts lots with any statutorily defined critical areas from middle housing requirements. Lots with only a small portions of a wetland buffer or slightly steeped slopes falling on them are common in cities and usually still accommodate dense urban housing on them, so cities allowing middle housing development on them would be consistent with the prevailing paradigm.

- Measuring walking distances from major transit stops could be accomplished in several ways, depending upon local considerations. Commerce suggests deciding whether to start measuring from the center point of a major transit stop or the outer bounds of it and then measuring by using a simple radius or doing detailed pathfinding to determine the “walking distance.”

The middle housing law does have several quirks that Commerce touched on, including how it deals with accessory dwelling units and with affordable housing requirements.

“A city may allow accessory dwelling units to achieve the unit density required in subsection (1) of this section,” the law states in part. Commerce says that cities can choose to make accessory dwelling units count for the purposes of unit density provisions, but the degree to which that might impact the law’s effect remains to be seen.

In certain cases, Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities must allow for certain levels of density provided that prescribed affordable housing contributions are made in a middle housing development. For instance, in a Tier 2 city outside of major transit stop area, four middle housing homes are allowed if one of those is affordable. The affordable housing requirement, however, would not apply to zoning for five or more middle housing units per lot.

All in all, Commerce provides a variety of policy guidance for local governments to consider and the model codes set a floor off of which cities can benchmark. But the final guidance and model codes could change, depending upon feedback received on the drafts. Commerce has an open comment period on the drafts through December 6. Finalized model code documents are expected to come early next year.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.