WSDOT wants to quit its highway expansion ways and adopt a fix-it-first policy. Will the legislature listen?

Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) Secretary Roger Millar is fond of reminding people that there are two things that he doesn’t get to do as head of WSDOT: appropriate money or set policy. The remark usually serves as a reminder for what types of work that his state agency actually does, and it also highlights the amount of power that the Washington State Legislature holds over the state’s transportation system. That body does appropriate money, and it does set policy.

But while WSDOT doesn’t technically set policy, it does recommend, advocate for, and even set the terms for many of the policy debates around transportation that happen around the state. State legislators frequently rely on the policy expertise that’s available within WSDOT, and the reports and studies that are produced within the department frequently end up integrated into standalone legislation and the state transportation budget. So while Millar’s line is true, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

The state Highway System Plan (HSP) is a key example of how many of these recommendations bubble up and become official policy.

Required by state law since 1996, the plan is a roadmap (so to speak) for the legislature, tasked with identifying both program needs for state highway facilities and the financial resources required to be able to implement them. Past versions of the plan have included a menu of highway projects for the legislature to prioritize. The 2007 update includes projects that are still under construction right now: the North Spokane Corridor US 395 expansion project, the “Puget Sound Gateway” extension of SR 167 and 509, and the Columbia River bridge between Washington and Oregon to cite just a few. But things look very different for the state transportation system now than they did in 2007.

After years of work and public outreach, WSDOT has released a new draft version of the Highway System Plan, and it actually represents a fairly substantial shift from how the state highway system has been operating for the past few decades. But because WSDOT and its leaders don’t set transportation policy or appropriate money, it will be up to the legislature to get on board with the significant change that it represents.

The Plan Recommends a Full “Maintenance First” Approach

Secretary Millar is also fond of another turn-of-phase to try and convey the scale of the state’s maintenance backlog when it comes to state highways: that Washington is currently on a “glide path to failure.” Current maintenance spending is only able to fund around 40% of what’s needed at any given time, not enough to even stay on pace as infrastructure ages, putting the state on track to have to shut some parts of the system down that can’t be properly maintained.

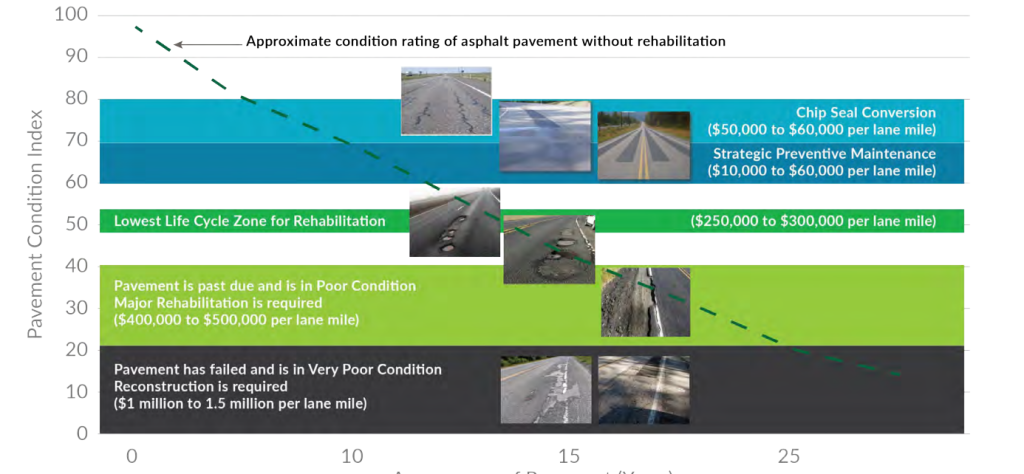

Millar’s use of the phase generated a fair amount of media attention when he used it earlier this year, but he has been saying it throughout his tenure as head of WSDOT, because the legislature has consistently found other priorities for transportation funding that were not maintaining the infrastructure that already exists. In 2019, 37% of the state’s total lane miles on state highways were reaching the need for maintenance, some as many as four years past due… by this year that number increased to 59%. And tackling maintenance needs earlier is actually more cost-effective.

The proposed HSP recommends the legislature go all-in on funding highway repair projects, noting overwhelming public support for maintaining what currently exists. “During community engagement the public overwhelmingly rejected the idea of closing or placing new limits on some bridges and highways in order to spend money on other highway programs,” the plan notes.

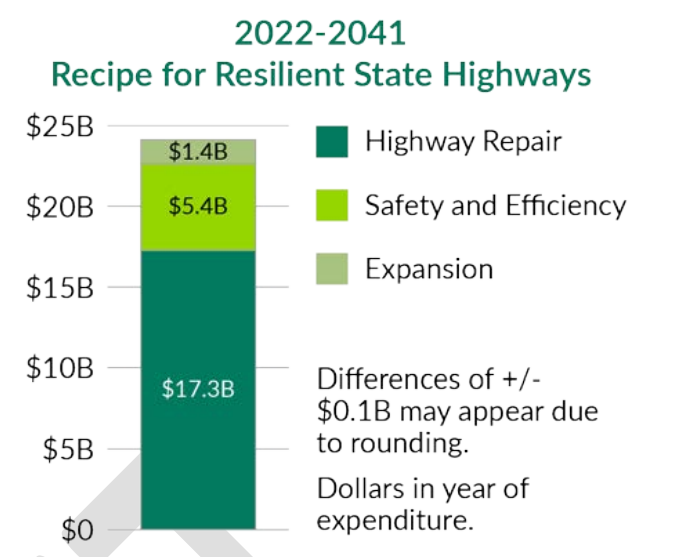

It recommends spending $17.3 billion over the next 20 years, close to $1 billion every single year, on rehabbing, repaving, upgrading, and repairing the state’s existing highway network. With the leftover funds, it recommends spending on new safety infrastructure and efficiency projects (like ramp metering) over new and expanded highways at a ratio of two-to-one. If implemented, this would be turning current transportation spending priorities on their head.

“While this recommendation is a significant shift from current practices, it responds to public preferences and is consistent with professional best practices,” the plan states. “This recipe for resilience will provide more positive economic, safety, and equity benefits to more Washingtonians across the state, enhanced by the state’s new complete streets and environmental justice requirements. It will enable WSDOT to progress toward making the system as safe as possible and getting the most we can out of the existing system.”

Maintenance Spending Is Now Safety Spending

After direct maintenance dollars, the second highest priority for the state transportation network outlined in the HSP is safety spending, as traffic fatalities in Washington hit levels that haven’t been seen since the 1970’s. Despite having a “Target Zero” program aiming to eliminate traffic deaths in place since 2000, one of the first in the country, actual spending on safety hasn’t followed. “I think we all get that we’ve got to do something more than say ‘safety first,'” Secretary Millar said earlier this year to a gathering of state highway officials in Seattle.

A huge swath of Washington’s highway network currently lacks basic infrastructure that keeps people safe: simple accommodations for people who aren’t in cars. The state highway network currently has around 550 miles of missing sidewalks, just on segments that run through population centers. There are over 1,100 miles of state highways through those same population centers that lack bike infrastructure.

Thanks to a provision in 2022’s Move Ahead Washington transportation package, every major maintenance project that WSDOT begins has to be evaluated for its potential to fill in gaps in the state’s bike and pedestrian networks. This Complete Streets mandate is a major way that Washington is going to be able to correct some of extreme deficiencies of the state highway network without the legislature allocating funding for each project individually.

Just a few months after it was passed, some results began to be seen publicly, with a planned revamp of State Route 99 through Edmonds retooled to include protected bike lanes — an element that would have been unthinkable for one of the state’s busiest highways only a few years ago. But while the Complete Streets mandate was a huge step forward, the legislature didn’t follow up with enough maintenance funding in the 2023 transportation budget to actually start the pipeline of needed upgrades.

“We’re in this space where the legislature will signal [that] they’re getting the message,” WSDOT Deputy Secretary Amy Scarton told the Washington Transportation Commission this past October. “And yet when it came time to put the money where the policy is… we at WSDOT were less-than-enthused that we didn’t see those numbers go up.”

“At first thought, we were so excited that we were going to be bringing [in] many projects across the state, not just coming into a community and fixing the state road,” Scarton said. “We will be fixing or adding the sidewalks, fixing or adding bike lanes, to really create a multimodal state transportation system. But when you loop back to the issue that they underfunded preservation, we’re not having a lot of new projects getting underway for complete streets. And it’s a direct result of the underfunding of preservation.”

Minimizing the Role of Highway Expansions

Prioritizing maintenance and safety infrastructure also means moving away from the era of the transportation megaproject that Washington finds itself in right now, with new and bigger highways the main dish of the state transportation budget meal. “Shifting from the construction of new and bigger highways to investing in preservation, safety, and efficiency strategies would provide more positive economic, safety, and equity benefits to more Washingtonians across the state,” the draft HSP notes.

This recommendation reflects a shift in thinking inside the department around the best use of transportation dollars. “Solving congestion by adding capacity to the system, it’s not economically possible, it’s not geographically possible,” Secretary Millar told the state senate’s transportation committee this past January. “It’s time to think about a different way of doing business. The first thing we need to do is get more out of what we’ve already built.”

The department is also getting more forthright about the negative impacts that continuing to expand the state highway network will have. A report that the legislature requested from WSDOT in 2021, detailed all of the ways that current state transportation policy cuts against the goals embedded in law around reducing vehicle use and creating more compact communities.

“Potential highway expansion, as opposed to other transportation investments, generally increases vehicle miles of travel by making access to land further away more attractive than it previously was,” the initial technical report on the issue noted. “On the other hand, investing in transportation efficiencies helps communities lower vehicle miles of travel by locating people closer to the activities they wish to engage in and providing them with transportation choices other than driving alone.”

WSDOT followed up with an official recommendation to evaluate any new projects for increased vehicle miles traveled, including the impact of induced demand — the idea that increased usage will cancel out the impact of any expansion project by prompting more travel, putting the state back at the place where it started.

But as the state legislature starts to consider the next transportation package after Move Ahead Washington, flagship expansion projects in each member’s district will tend to be much more appealing than small projects scattered around the state, no matter what the long-term impact of those projects will actually be. Many of those projects, like a new trestle along US Route 2 in Snohomish County, or a widened SR 3 in Kitsap County, have been long “promised” and remain intact in local and regional plans.

“I’m not so sure, actually, that it’s that we need more funding, that we need more sources of funding,” Deputy Secretary Scarton told the transportation commission. “We have more funding now than we’ve ever had in the history of transportation in our state — from our state revenues, from our federal revenues — it’s that we now have more funding than ever in the history of our state being directed to new build projects in lieu of preserving the ferry system, preserving the roads, preserving the bridges.”

It will be up to the legislature to decide whether to shift those priorities, but an escape hatch for the “glide path to failure” seems to be right under their noses.

The draft Highway System Plan is open for comment until December 18. This Thursday, November 30, at 2pm, WSDOT is hosting a virtual meeting to discuss the plan.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.