Bollards are on the way to protect pedestrians.

When the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) wrapped up installation in mid-2022 on what had been intended to become Seattle’s largest raised street crossing, at Melrose Avenue and East Pike Street in Capitol Hill, reactions to how it turned out were far from positive.

Installed as part of corridor-wide upgrades with the “Melrose Promenade” project, the feature was a fairly ambitious design for an urban neighborhood greenway: a traffic calming feature intended to take over the entire intersection from Pike Street all the way to the foot of Melrose Market. But, for one thing, the “raised” part of the crosswalk appeared to be missing: To most visitors it looked more like the curb on the street had simply been removed, and the street repaved with brick material, which is actually stamped concrete.

It’s easy to understand what the raised intersection was intended to do at Melrose and Pike. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), one of the more forward-thinking US bodies focused on making recommendations on urban streetscape design, describes a raised intersection as creating “a safe, slow-speed crossing and public space at minor intersections,” and compares their intended effect to that of a mid-block speed bump, intended to “reinforce slow speeds and encourage motorists to yield to pedestrians at the crosswalk.”

But the new intersection at Melrose and Pike didn’t seem to slow drivers much at all, and the new curbless street made it easier for drivers to pull off to the side for any amount of time, even though parking isn’t allowed on the raised intersection. People walking or biking through had to contend with drivers coming in either direction as well as ones pulling out and into illegal parking spots.

Now, well after work wrapped up on the initial project, SDOT has announced that it plans to implement changes at the intersection in response to community feedback — criticism that could have been anticipated well in advance of construction. SDOT will add bollards, which are recommended by NACTO as part of raised intersection design but which weren’t part of the plan for Melrose and Pike, along with bike racks intended to discourage drivers from illegally parking or idling. Those bollards are set to be installed in 2024.

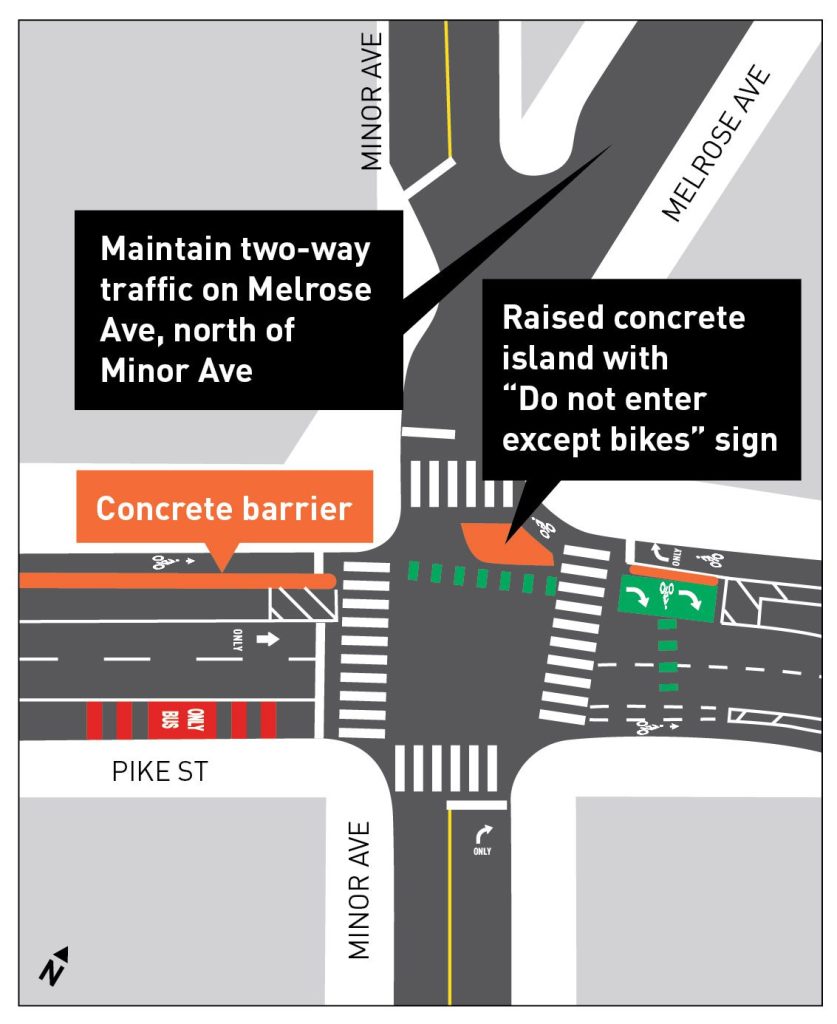

In addition to bollards, the department also announced that it would be adding additional restrictions on how drivers can access the intersection: it’s already illegal to turn left from Pike Street onto Melrose, after these changes it will no longer be legal to drive straight across Pike from Minor Avenue either, and a new concrete island will make it more clear that these movements are prohibited. The concrete island was already planned as part of the bike lane being installed on Pike Street, but these new signs laying out access restrictions were not part of those plans.

Ultimately, it was concerns from residents and safe streets advocates that were able to prompt the department to rethink things at this spot. “These changes will make the street more comfortable for people walking, biking, and rolling,” the department said as it made the announcement earlier this month in a blog post. “They’ll also address issues of illegal parking and illegal left turns from E Pike Street onto Melrose Avenue.”

Local advocacy group Central Seattle Greenways held a walking tour with SDOT Director Greg Spotts this past March and visited the intersection to discuss their concerns. Their advocacy helped secure the change.

“We were very pleased to see the announcement, and expect the changes to create a much safer, less confusing, and more comfortable space for people traveling to and through that area – especially for people walking and rolling,” Brie Gyncild, co-chair of Central Seattle Greenways, told The Urbanist. “We appreciate that SDOT listened to our concerns and worked with us, nearby businesses, and other community members to find a solution that should work well for everyone.”

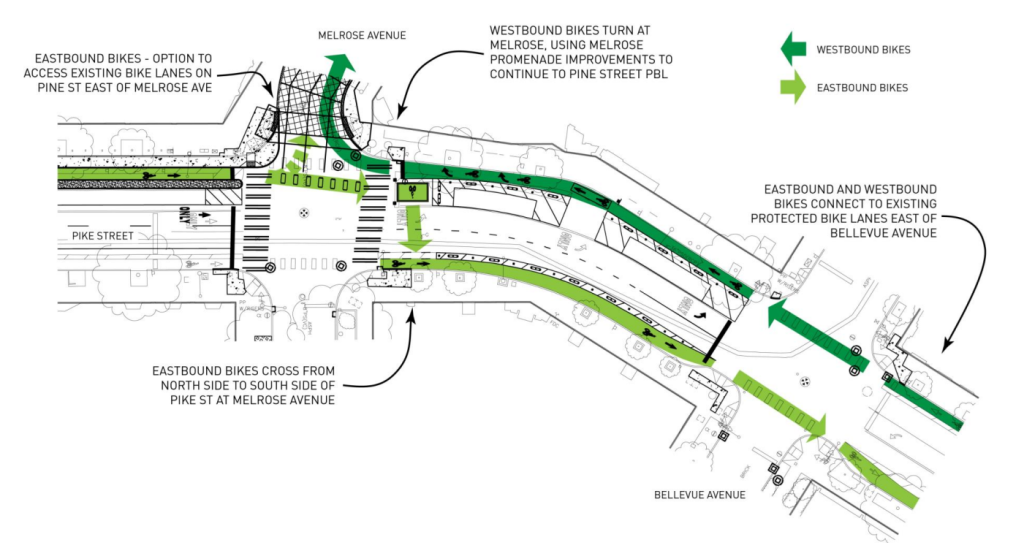

With traffic revisions in progress that will extend the one-way traffic patterns on Pike and Pine fully into Capitol Hill up to Bellevue Avenue, Melrose Avenue will become an even more critical bike connection. With no upgrades planned to Pine Street’s paint bike lanes east of Bellevue, Pike Street will remain the only street with separated bike lanes heading in both directions in Capitol Hill. Heading toward downtown, riders will be directed over onto Pine Street once they reach Melrose. Diverting some of the traffic away that’s simply trying to access I-5 or cut through the neighborhood will make the short block of Melrose between Pike and Pine better for everyone.

In its announcement, SDOT noted that they evaluated making Melrose Avenue southbound only for that one block, but aren’t moving forward with that option because it needs to support two-way bike traffic. The design of Bell Street in Belltown, which is designated a two-way bike facility but is one-way only for people driving, undermines this claim. But it also serves to highlight the opportunities that were missed here, for a block that could clearly be one of the most people-centric blocks in the entire city.

Seattle residents got a very tiny taste of what Melrose could have become during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, when SDOT issued a permit for nearby restaurants like Mamnoon and Terra Plata to be able to utilize nearly the entirety of the street for outdoor dining. Traffic patterns in the neighborhood adjusted, and the block was turned over to people. Even though the setup only lasted for a few weeks in mid-2020, it showed the vast potential that the street had — and still has.

But by that time, plans for the Melrose Promenade had already been drawn up, and fundamentally rethinking how the block operated had been discarded as an option early on. Now, three years later, the conversation has shifted to how to mitigate what we’ve already done.

Much like the last-minute change pedestrianizing the 100 block of Pike Street at the front door of Pike Place Market, the moves to improve key design elements after these projects were implemented are positive steps. But it’s pretty clear that if a different approach had been applied from the start — one that takes into effect fairly well-known international design standards along with longstanding city goals — the results would have been fundamentally different. And significant city staff time and expenses could have been saved. The only thing left to do is to learn from our mistakes.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.