Ron Davis is losing by 240 votes, and 524 fewer young D4 residents voted in 2023 compared to 2019.

In the days leading up to the Seattle City Council election, street posts around the University of Washington were plastered with concert flyers and Palestinian flags, but not a single campaign sign. Youth largely sat the election out: In the most recent citywide tally, only 3% of ballots were cast by 18-24 year-olds, despite that demographic representing around 10% of Seattle’s population.

In District 4, which encompasses UW with its 50,000 students, progressive, Urbanist-endorsed Ron Davis trails business-backed Maritza Rivera by a mere 240 votes in the latest count Friday. Fewer young voters cast their ballots in D4 in 2023 than 2019. Could UW student voting turnout have made the difference for Davis?

Ron Davis’s campaign manager Diego Batres devoted considerable resources to UW outreach, but concludes, “I say this affectionately, having just graduated myself, that students are just very fickle. And organizing students can be very fickle.”

Batres points to the timing, for one thing. Primary elections occur in the summer, when campus is hollowed out. By the time the general rolls around, students are distracted with midterms.

Second, young people move around a lot, and may not update their registration, says Seattle University professor Patrick Schoettmer. Ballots get lost or misplaced all the time. Plus, convincing students to change their registration to D4 is a tall order, when most see their dorm as merely a temporary home.

“If [progressives] want to get students to be more engaged in Seattle politics, you’ve got to convince them that they’re spending the next four years of their life there, and if they’re 18 when they’re coming in, and they’re 22 when they’re coming out, that’s like a fifth of their whole life [up to that point],” Schoettmer says.

Young people are harder for campaigns to track down, too. Older voters are a safer bet, with their landlines, established addresses, and willingness to talk to strangers. The dominant divide in Seattle politics isn’t just between The Stranger endorsees and the Seattle Times picks, but between renters and homeowners, Schoettmer says. Hence why yard signs tend to skew conservative (by Seattle standards). Canvassing in the dorms presents a challenge, too, as students are not allowed to put up non-approved posters or slip pamphlets under doors.

“Any campaign that is building its campaign around turning out renters and turning out young people begins in a hole. You have to work harder from the outset,” Schoettmer says.

Famously, one Seattle campaign did seize on the youth vote: Kshama Sawant. Not only were her posters ubiquitous, but her volunteers would constantly email Schoettmer asking if she could speak to his class. Neither District 3 candidate from this year, Alex Hudson nor Joy Hollingsworth, reached out to him.

“Sawant’s great gift was that she understood that campaigns are effectively a competitive storytelling event. She knew how to drive a message, and she knew how to get attention. And that’s what you have to do if you want to mobilize and capture the attention of younger voters,” explains Schoettmer.

In 2019, D4 candidate Shaun Scott followed the Sawant playbook. Preliminary data suggests that Scott turned out more young people than Davis, although final precinct-level results won’t be available until later this month. Just over 2,000 young voters cast their ballots in 2019’s D4 race, but votes cast by people ages 18 to 24 dropped by 25% in 2023, according to Tim O’Neal, senior research analyst with the WA Community Alliance.

- 2019: 2,055 votes cast by 18-24 year olds (7.1% of all D4 votes).

- 2023: 1,531 votes cast by 18-24 year olds (5.3% of all D4 votes).

Note that redistricting may have played a role, with D4 losing Eastlake but picking up more of Wedgwood in the new map approved last year. Nonetheless, there’s a case to be made that Davis would have won with 2019 levels of youth turnout — predicated on him winning about three-quarters of those extra votes.

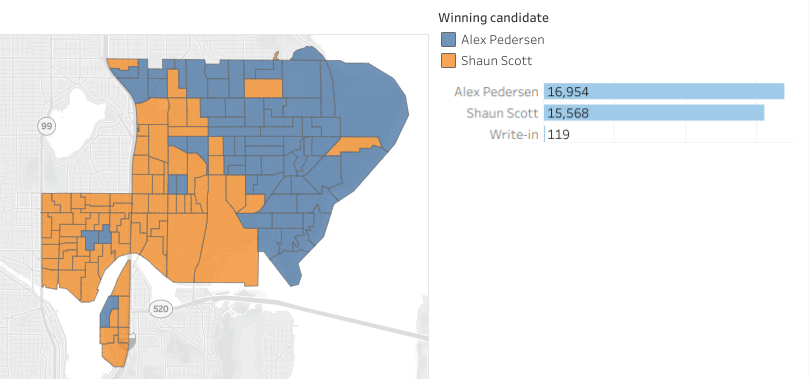

Another factor at play: Scott’s more unabashedly progressive, revolutionary message both attracted and repelled: he ultimately lost to opponent Alex Pedersen by four percentage points, largely because Pedersen ran up the total so much in wealthier single family neighborhoods. But Scott’s fiery message may have helped him in the U District.

Preliminary election night results (visualized below courtesy of Jason Weill, with Davis precincts in blue and Rivera in orange) show abysmal turnout and some unexpected strength for Rivera on UW campus, but that may flip in late results as more late-voting progressive votes come in. Overall the race shifted 10 points from election night, just shy of the 11 points Davis needed to close the gap. Meanwhile, Scott’s final results map from 2019 shows nearly a clean sweep of the U District.

As Batres jokes, “I’ve definitely heard someone say, ‘If Shaun Scott’s yard signs looked less Soviet, he might have won.’ We’re looking at a district where you need to be able to pitch yourself as totally reasonable and practical, not a crusader, not a zealot. The youth sometimes need that energy to get really hyped up and involved. And Ron couldn’t afford to come off that way.”

“There was enough red-baiting already, can you imagine if he had actually said something like ‘defund the police’? The numbers would have been even further apart. Not that they’re very far apart now,” says Batres.

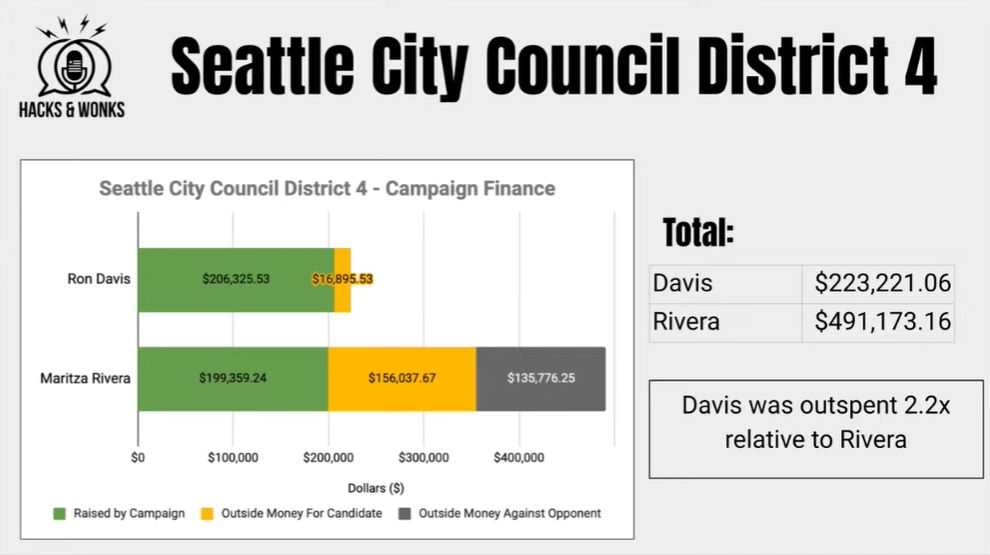

Even though Davis was careful to say he didn’t agree with the idea of defunding the police, Rivera’s campaign still branded him as a defund backer all the same, and stressed this message in mailers and debates. Davis made correcting the record the top fact-check on his webpage, but the message may have been drowned out as Rivera raised 2.2 times more money with the help of outside spending from political action committees. More than $135,000 in negative attack ads continued to carry the message that Davis supported defunding the police.

Torn between taking more radical positions to mobilize the youth vote and guarding against attacks of being “extremist,” progressive campaigns are left with two dicey options.

The first is to reach out to student activists such as the UW Democrats, the Students for a Democratic Society, and Institutional Climate Action, as Davis did, in hopes they can win over the most engaged students. Such organizations tend to grill candidates on their leftist bona fides. Batres recalls organizations’ “purity tests,” such as criticizing Davis for the “Million Dollar Club” salesman award on his LinkedIn page.

Indeed, Students for a Democratic Society leader Yumiko Minamoto was cautious in her endorsement, noting the group’s goal of police abolition. “We thought that he was a step in the right direction,” says Minamoto. When compared with Rivera, “One can be reasoned with and the other one can’t.”

Still, Batres notes that Davis’ base of urbanists includes plenty of students, particularly those keenly interested in urban planning and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math).

The second option is to attempt to mobilize the unengaged populace, particularly among students and tenants that tend to sit out odd-year elections. That’s an uphill battle given widespread “disillusionment” and “apathy” towards politics, Minamoto says, especially during the Biden presidency.

So what’s next? Barring a late miracle adding more ballots into the mix, Rivera will win the D4 race by about 240 votes when King County Elections finalizes results on November 28. While such a miracle is unlikely, the revelation of at least 85 ballots undelivered due to a malfunctioning mailbox in District 3 has kept hope alive in the Davis camp.

“It’s unclear if that was a one-off or not,” says Batres. As progressive campaigns urge voters to check that their ballots have been counted, Batres says the fight isn’t over yet.

“It’s not gonna reverse the trend we’ve seen across the city, but in some races as close as Ron’s, an extra 80 ballots could mean everything.”

If one broaches this subject with UW students, however, the response is likely to be, “What election?” For most students, with Thanksgiving break on the horizon, thoughts have turned away from politics and towards turkey.

Alison Jean Smith

Alison Jean Smith is the Local Sightings Director at Northwest Film Forum, a member of the TeenTix Alumni Advisory Board, and a contributor to REDEFINE, an online magazine where she interviews both emerging and established filmmakers. She has also had her writing published in The Stranger, The South Seattle Emerald, and on the doubleXposure podcast website. Topics she’s covered range from wild horse training to debates over light rail. She is currently studying communication at the University of Washington.