Agency leaders argued simple fares are better, even if it meant much steeper fares for short trips.

Sound Transit is queuing up a major fare hike for most of its light rail riders, hitting those taking shorter trips particularly hard. Staff are recommending that flat fares replace distance-based fares on Link, even though budget-neutral versions of this would reduce ridership and discourage shorter trips compared with retaining distance-based fares. A $3.25 flat fare would constitute a 30% increase for the two thirds of riders who today pay the lowest two fare tiers: $2.25 or $2.50. A $3.50 flat fare, meanwhile, would constitute a 40% fare increase for those riders.

Comments in favor of a more regionally equitable zone-based fares appeared to have failed to move the needle at the agency, which increasingly is putting its weight behind flat fares.

Over the past few months, agency staff have been laser-focused on the simplicity of flat fares over their impact to riders, and trying to mirror cherry-picked American peer agencies as further justification for the move, even though the agency’s latest survey results and quantitative data point toward retaining distance-based fares.

Link isn’t alone in distance-based fares. San Francisco’s BART, Washington DC’s Metrorail, and Philadelphia’s PATCO use them, for instance, with a wider array of other prominent American transit systems using zone-based fares for rail. Even Sounder commuter rail has distance-based fares, a commonality between the agency’s own rail services.

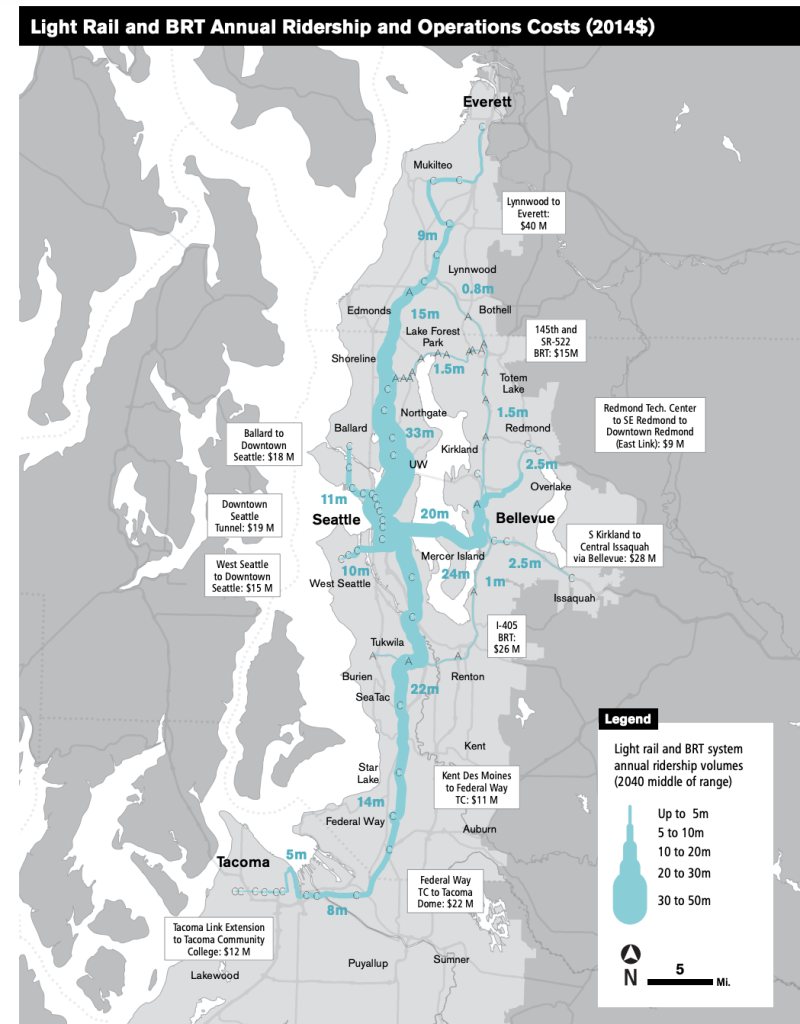

Distance-based fares mostly impact riders who travel longer distances. Riders traveling shorter distances are rewarded with lower fares. Changing this paradigm would mean that most riders who travel shorter distances would be cross-subsidizing riders traveling longer distances who use more resources. It’s not a very equitable trade, especially in a system set to grow to some 116 miles in the coming years, becoming the country’s second largest light rail system.

Sound Transit has been considering several potential fare change scenarios: increasing distance-based fares by $0.25 or $0.50, or instituting a flat fare at $3.00, $3.25, or $3.50. Among these though, the $3.00 flat fare would be the only scenario not financially responsible because it would increase debt pressure for the agency and is unlikely to be adopted. All of the other scenarios would create no negative impact to the agency’s debt capacity and coverage ratio.

Based upon spring data, Sound Transit reports that more than 66.7% of riders that tap on and off with ORCA spend $2.50 or less. Under the highest distanced-based fare option, these riders would continue to save money over the least costly and financially viable flat fare option ($3.25) under consideration. Another 19.8% of those riders would see no benefit from a move to the least costly and viable flat fare option.

Ridership models show that all fare change options would reduce ridership. For distance-based fares, ridership loss would be 3% for a $0.25 fare increase and 6% for $0.50 fare increases. For viable flat fare options, ridership loss would be 6% for a $3.25 fare and 9% for a $3.50 flat fare.

Most Link riders usually don’t have to think about fares though. That’s because 54% of Link riders participate in a reduced or free fare program or have an employer-paid transit pass. Tapping on for these riders is usually enough to cover the reduced or retail cost of the ride without worrying about the cost.

The fare revenue and farebox coverage estimates, however, really tell the tale of why a flat fare system would be inequitable. As the data bears out, it would raise more revenue, mostly off the backs of riders who make shorter trips today.

| Fare Change | 2027 Fare Revenue | 2027 Farebox Recovery | 2017-2046 Fare Revenue | 2017-2046 Farebox Recovery |

| Distance-Based: $0.25 increase | $94 million | 17% | $4.2 billion | 19% |

| Distance-Based: $0.50 increase | $99 million | 18% | $4.4 billion | 20% |

| Flat: $3.25 | $103 million | 19% | $4.4 billion | 20% |

| Flat: $3.50 | $111 million | 20% | $4.7 billion | 21% |

Another dimension that bears out the disparate impacts of a flat fare system would have on most riders is shorter trip scenarios:

| Trip Pair | Current Cost | Distance-Based Options | Viable Flat Fare Options |

| Capitol Hill to Westlake | $2.25 | $2.50 or $2.75 | $3.25 or $3.50 |

| Northgate to University of Washington | $2.50 | $2.75 or $3.00 | $3.25 or $3.50 |

| Rainier Beach to Pioneer Square | $2.50 | $2.75 or $3.00 | $3.25 or $3.50 |

| Beacon Hill to Columbia City | $2.25 | $2.50 or $2.75 | $3.25 or $3.50 |

| Federal Way to Kent/Des Moines | $2.75 (RapidRide A Line) | $2.75 or $3.00 | $3.25 or $3.50 |

Moving to a flat fare system wouldn’t be the first time Sound Transit has done so for a premium transit service. The agency implemented one for ST Express bus service in 2020, ending a zone-based fare system instead of adjusting it to be more regionally equitable. Previously ST Express featured a one-zone fare that was $2.75 and a two-zone fare that was $3.75. Those fares were folded into a single $3.25 flat fare, benefiting long-distance riders crossing county boundaries and penalizing short-distance ones in King County. Community Transit charges considerably higher fares for their cross-county express routes at $4.25.

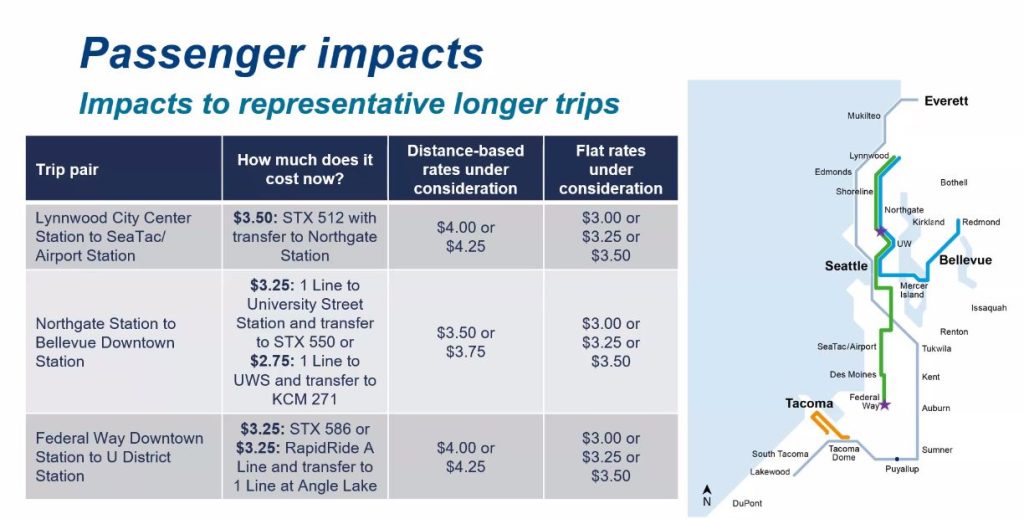

Agency staff cited how a long-distance trip from Lynnwood to Sea-Tac Airport would be higher under distance-based fares since they could reach $4.00 or $4.25 versus $3.50 now with a ride on the Route 512 bus and transfer to Link. But this belies the fact that fares would cost $4.00 or more now for those Route 512 riders had zone-based fares not been eliminated during the pandemic and gone up as scheduled.

The agency also tried to stack up fare costs for a trip from Bellevue to Northgate on the future Link 2 Line versus the Route 271 bus and Link. Smart riders are likely to do the transfer option via University of Washington station, which is more time efficient (26 minutes) than riding the 2 Line (39 minutes) south and back north. Ultimately, the transfer would keep the fare costs cheaper under distance-based fares.

How Sound Transit staff is arriving at a flat fare is simply head-scratching. Their research is clearly pointing them to keep distance-based fares and survey results show that most current riders don’t want flat fares. Riders still have time to lobby the board and staff to change course with two upcoming meetings in December, but they may face an uphill climb.

At Thursday’s board meeting, System Expansion Committee Chair Claudia Balducci signaled support for flat fares, arguing removing the need to “tap off” Link after completing a trip would reduce rider confusion and anxiety, and potentially encourage ridership in its own right. Pierce County Executive Bruce Dammeier agreed with that sentiment, but not before making a point to say he wanted to make sure riders tapped on to pay their fare.

On the flip side, Board Chair and King County Executive Dow Constantine expressed some misgivings about the flat fare idea, noting it would penalize people who choose to live in transit-oriented housing (which the agency is encouraging with its transit-oriented development program) in order to have shorter commutes on the train. The chair also questioned the staff recommendation to approve the flat fare structure before setting the exact fare.

“It’s very hard to decide between a flat fare and a distance-based fare unless you know what the flat fare is,” Constantine said. “A flat fare of $3.50 would still be a bargain for those who live at a great distance or who live in less densely populated communities, but would be a really significant increase for people who have chosen to live in most transit-oriented communities.”

Riders can contact the agency board at emailtheboard@soundtransit.org and meetingcomments@soundtransit.org.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.