The State has a role in defining the market for freight and charting emissions reductions with a shift to rail.

When the Washington State Legislature passed the Climate Commitment Act (CCA) in 2021, it codified economic decarbonization as the government’s priority. To this end, the law created an ambitious emissions market system with two primary goals:

1) Incentivizing consensual private decarbonization.

2) Increasing revenue for investments in socially and environmentally sustainable infrastructure projects.

The policy fits neatly into the ideological constraints written into Washington’s legal code: it specifically recommends market solutions while ignoring the government’s role in constructing the market’s operational infrastructure.

Ironically, cap-and-invest’s market-oriented solution implicitly acknowledges the state’s essential role in directing the economy. Disparate private enterprises cannot adequately respond to major social crises: They specialize in narrowly enhancing profitability within extant economic structures. It is the government which creates those structures, and the CCA builds a financial incline directing the flow of money towards sustainability.

However, monetary structures cannot accomplish change if people lack the physical structures which permit them to choose differently. For transport logistics under the CCA, this means a shift away from the less energy efficient freight modes and projects, such as trucking, and towards more efficient ones, like improving and expanding the state’s underfunded short-line rail network.

Given the structural incentives of the CCA, it’s worth interrogating how the legislature has seen fit to develop the Puget Sound Gateway Project, an initiative to build multiple highway extensions, interchanges, and overpasses to better link I-5 to the Port of Tacoma, Sea-Tac, and the Port of Seattle. How sustainable are the current freight mode shares between these areas, and how might this project impact the current mode distribution?

Dependence on trucking will disrupt business under CCA

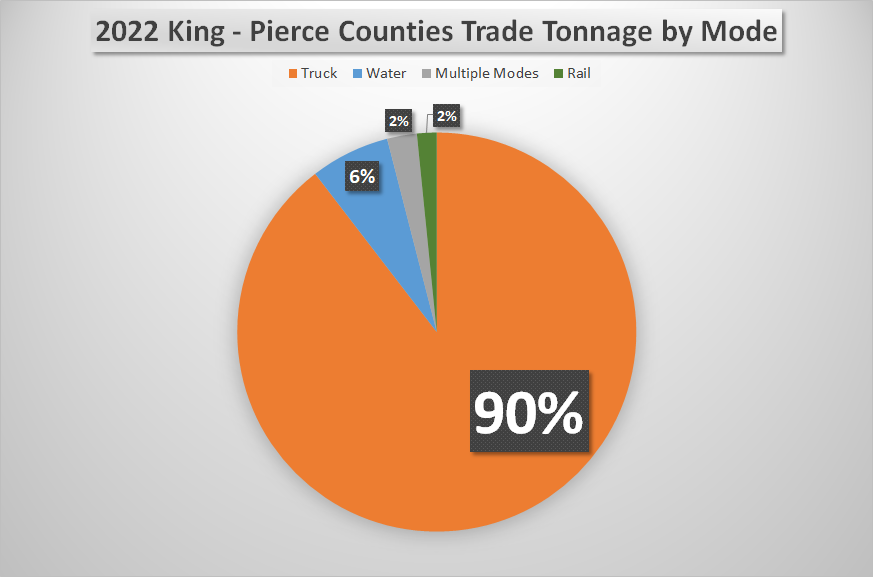

Currently, King and Pierce counties together represent one of the state’s most vital logistical centers: They host the third largest port complex in the country and exchange tens of millions of metric tons per year. Though economically vibrant, the dual-county area’s logistical network relies on trucking for 90% of its trade by weight, meaning the CCA will risk inhibiting the region’s economic performance unless the state provides physical infrastructure for companies to choose more efficient freight modes.

As it was unwise for many of Washington’s 20th century homes to have been built with poor insulation – founded upon the shaky assumption that the Columbia River Basin dams’ abundant electricity would eternally and infinitely outpace demand – it is unwise to rely on a logistical network where costs rest on the the very means the state seeks to make prohibitively expensive.

Fortunately, the CCA’s focus on investment signals that the legislature has recognized this issue and plans to build off-ramps from carbon-intensive highways to more socially and environmentally conscious transportation infrastructure. At least, that is what the language of CCA signals, though the budget indicates otherwise.

State transportation funding is inconsistent with its climate policies

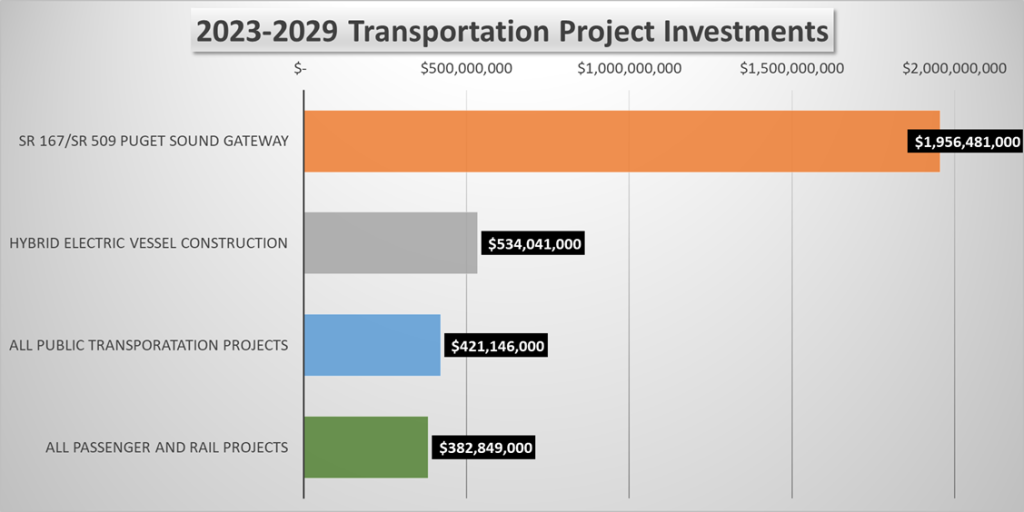

A pro-business ecologically conscious government committed to fulfilling its own legal emissions mandates would likely invest in shifting freight share away from trucking, especially for traffic between the state’s most significant ports. After all, the State plans to invest more than half a billion dollars in constructing hybrid ferries, so it must also plan to electrify its freight and passenger rail corridors, given that transportation causes nearly 40% of the state’s current emissions and rail already transports 20% of the state’s cargo by weight, in spite of the previous century’s plans to build highway dependency.

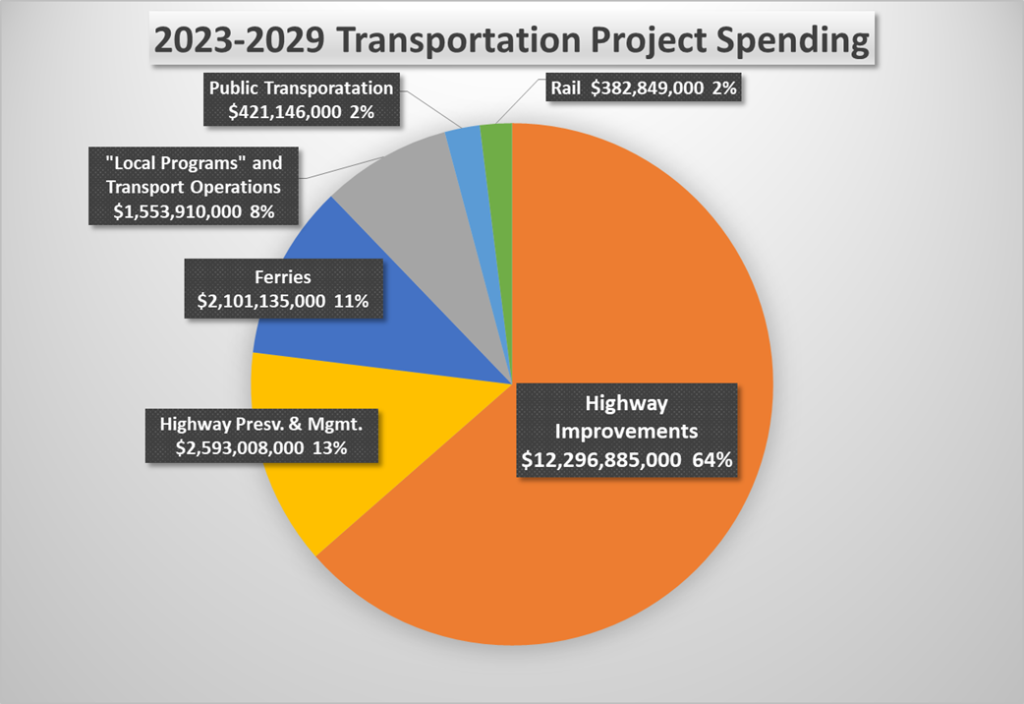

Unfortunately, the transportation project budget from 2023-2029 does not follow this logic. There are no plans for expanding or electrifying passenger and freight rail corridors; by mode rail will receive a mere 2% of the budget, coming in at $0.38 billion. Instead, the lion’s share of the transportation project budget is slated for highway improvements, with the single largest investment being the $1.9 billion reserved for the Puget Sound Gateway highway connections, more than five times all state investments in rail.

Both temporally and ideologically, the state remains constrained. According to Kris Olsen, the spokesperson for the Puget Sound Gateway Project, “both SR 509 and 167 were planned in the late 1950s and 1960s when most major highways in western Washington were planned and built,” meaning the state legislature is choosing to invest in projects conceived 30 years before we’d emitted more than half of our current atmosphere’s carbon. As the legislature has explicitly acknowledged the compounding consequences of climate change, it wouldn’t be beyond reason to expect them to scrap infrastructure plans reflecting priorities established before roughly 85% of the American population was born.

To the question of whether WSDOT committed to retaining trucks as a key pillar of land-based logistics in Washington, the WSDOT spokesperson responded, “We do not dictate the means of transport used by the private sector.” Though technically true, the statement betrays heavy market-ideological constraints, abdicating the state’s responsibility in creating viable alternatives for companies to utilize.

Beyond this, the specific decision to spend more than quadruple the entire rail project budget on a single highway corridor betrays a distinct windshield perspective on the part of legislators: They conflate transportation and driving, their ideological limits reflecting the physical transportation constraints they have likely grown up with. This can be best summarized by two notable linguistic choices:

1) Transportation infrastructure laws fall under the category “Public Highways and Transportation” in the Revised Code of Washington, and

2) The Puget Sound Gateway spokesperson stated one of the primary purposes of the project is “… creating new, more efficient driving options,” rather than creating more efficient transportation options.

This implicit erasure of modes beyond the road undermines the multimodal priorities established in the state’s ironically titled legal code. Gaining an appreciation of how a car-centric paradigm limits their perspectives would help legislators maintain consistency between the government’s various climate and transportation directives, and would ultimately assist companies in complying with the CCA’s emissions mandates.

If the state refuses to invest more than 2% of its transportation project spending in providing businesses with more efficient freight alternatives, how are companies supposed to choose a more efficient mode than trucking? Is it wise to continue to rely on gasoline when oil prices are prone to fluctuation due to global political strife? Regardless of external oil price shocks, the CCA will increase carbon-intensive logistical costs by imposing fines on companies. Continuing to fund reliance on highways through projects like the Puget Sound Gateway thus creates a Catch 22: The state will financially penalize companies for choosing carbon intensive practices while investing almost exclusively in carbon-intensive freight infrastructure. It’s as if the state passed higher tobacco taxes in order to curb consumption, then. increased cigarette advertising to children. It’s a great way to generate revenue, but socially, fiscally, and ecologically, it’s unsustainable.

Aligning transportation and climate policies is possible

Theoretically, the Puget Sound Gateway Project could secretly be a clever means of boosting state carbon fee revenues by inducing more driving. To my personal disappointment, because I enjoy schemes of legal and financial intrigue, it is not such a scheme, according to Olsen.

“The Puget Sound Gateway Program, at the direction of the Legislature, is focused on building these highway connections to the ports to complete the interconnectivity necessary for the efficient movement and transfer of goods using highways, railways and seaports,” Olsen said.

Since they had mentioned railways, and because multimodality and emissions limits are legislatively established priorities, I asked whether there had been any comparative evaluations on whether port connections might be better served by expanded and upgraded rail connections. As shipping large volumes between specific terminals quite succinctly defines the specialization of freight rail, a port connection via rail would seem a concept worth investigating.

Surprisingly, I was told Puget Sound Gateway planners “do not have any information that compares emissions from completing the SR 167 and 509 projects with emissions from rail or rail projects.” The specific environmental and economic reasons why the state will invest five times the rail budget in a single highway project appear confined to the heads of the legislators, rather than anyone at WSDOT.

Washington State does not require radically unprecedented change to reform its transportation sector: WSDOT planners have already located specific rail improvements to alleviate friction between freight and passenger traffic and have identified the short line rail network as a mode holding potential and requiring investment. The State doesn’t lack the funds to implement these meaningful changes, legislators are simply choosing to place $14.8 billion in highways and 38 times less in all the state’s rail projects. The money slated for the Puget Sound Gateway could revitalize rail across the entire state, but the legislature has chosen to completely squander this potential.

If the state wants to operate effectively, it needs to operate with internal consistency. Investing billions in projects which will specifically undercut parallel objectives will lead to the state disrupting its own projects. Any wise politician would pay attention to the potentially catastrophic political blowback from failed policies. The legislature has formulated an innovative and ambitious market-based solution to emissions, now it needs to follow that up with the requisite state-based solutions, or risk seeing those priorities scrapped after a lost election.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.