Facing a housing slowdown, foisting more costs onto new homes to fund a hodgepodge of transportation projects is a terrible idea.

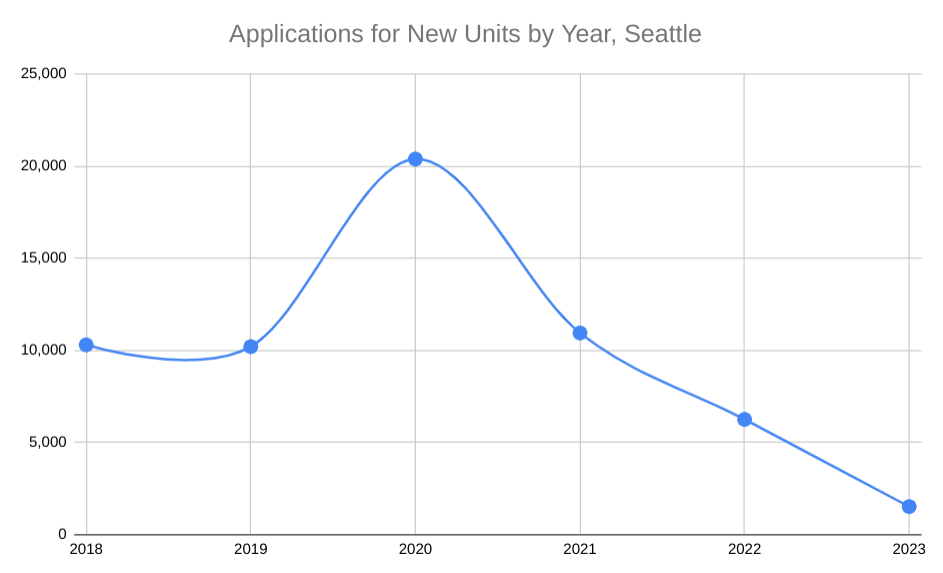

The four members of the Seattle City Council who are set to retire are making some last bids to cement their legacy and pass some major legislation on their way out. For Lisa Herbold and Alex Pedersen, perhaps the biggest white whale they’re after is taxing new housing to fund transportation projects via transportation impact fees. Doing so now would be a terrible mistake: Housing permits are already in sharp decline even before adding another obstacle to the mix.

Better to leave the discussion to a future council not stuffed with four lame-duck members focused on their personal bucket lists and vendettas against homebuilders; these proposals do not serve their constituents’ needs. If the City were to implement impact fees, it certainly would be wiser to apply them amidst a housing boom rather than a housing bust. Seattle needs to build more homes, and kicking builders while they’re down is not the way to do it.

In 2023, housing permit applications reached their lowest level in a decade. With the housing pipeline at risk of drying up, the last thing we should be doing is adding costs and impeding homebuilding. This is housing policy malpractice.

The idea has long been discussed, with Councilmember Mike O’Brien leading a charge, hoping to implement them before he left office at the end of 2019. That charge came up short as the City focused instead on implementing a different developer fee: the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, and the baton passed from one transportation chair to another in Pedersen.

Four years later, the housing market has cooled off considerably, but Pedersen is forging ahead all the same. Interest rates have spiked, which adds huge borrowing costs for builders. Material and labor costs are higher, and builders have complained of Seattle’s strict new energy code adding costs too. And it being Seattle, builders also have to navigate a labyrinth of design approvals to get permits, sometimes encountering costly surprise fees along the way from departments like Seattle Public Utilities, who aim to get builders to pay for water system upgrades — effectively a hidden impact fee that is arguably illegal and not supported in code.

To this melange of obstacles, Pedersen and Herbold hope to add one more. Will this be the straw that breaks the camel’s back?

A council staff analysis found impact fees could bring in between $200 million and $760 million over a decade. The higher rates studied would be like adding another MHA program. Unlike the MHA program, which had years of process and outreach, impact fees are being jammed through with minimal process or public input, as supporters hope they can beat the clock on expiring council terms. There’s been no equity analysis or study of the economic impact on housing production, as there was with MHA.

Impact fees may be less popular among the incoming crop of leaders than the stalwart supporters among the retirees. Candidates like D4’s Ron Davis and D3’s Alex Hudson have come out staunchly against impact fees, and D1’s Maren Costa has expressed reservations. If they win, they’d replace three of the biggest supporters in Pedersen, Kshama Sawant, and Herbold, respectively.

Pedersen stated he liked impact fees because he thought they would offload costs from homeowners to developers. “In the spirit of progressive tax reform — which is long overdue in Seattle — imposing this one-time new fee on just new for-profit real estate development could, in turn, enable City Hall to LOWER an ongoing expense for everyone’s housing: the property taxes charged to everyone for future transportation projects,” Pedersen wrote in a blog post on his council website earlier this year.

This analysis is wrong and it betrays exactly the wrong kind of priority and motivation. Impact fees are even more likely to be passed on tenants than property taxes. Tenants contribute to property taxes just as surely as they’re hit by impact fees by the same mechanism: funding their landlords’ ability to pay said fees or taxes. Impact fees just hit tenants much harder, making them more regressive than property taxes. If landlords are able to pass on costs to tenants in the form of higher rents, they will do so. Tenants also pay more when homebuilding sputters, vacancies tighten, and landlords jack up rents. This is exactly what could happen if impact fees are implemented while heading into a downturn.

Pedersen’s motivation is as misguided as it is cold-hearted. Tenants tend to be lower income and have less wealth, so targeting them seems callous. The idea that tenants live on easy street in Seattle is surely spoken by someone who hasn’t been a tenant in a very long time. This is the type of move that somebody not running for election and looking to go out in a blaze of “get off my lawn” homeowner activist glory would do. Polls show housing affordability is increasingly a concern, and voters want leaders to increase housing, not obstruct it.

Mandatory Housing Affordability is a form of inclusionary zoning, but to homebuilders it functions nearly the same as an impact fee, with the difference of having a performance option to build affordable homes on-site rather than pay into the City’s affordable housing trust fund. Most developers opt to pay the fee, rather than build on-site. Effectively then, a transportation impact fee is a second bite of the same apple.

Supporters argue inclusionary zoning or impact fees act as land value capture: The cost of the requirement lowers the value of development, lowering the value of land. Theoretically, this means homebuilders would pay less for the land than they would without the affordability requirement. The Urbanist editorial board has supported MHA, in part, under the belief that land value capture would offset the hit to housing production. But the key difference was MHA linked the fee to an upzone that increased housing capacity and lessened the blow to homebuilders.

Transportation impact fees do no such thing. They provide no guarantee of direct benefit to the property since there is no limitation on where the funding is spent — it could next door or halfway across the city. In fact, many areas of the city have no projects on the proposed impact fee project list where revenues would be spent. Homebuilders experience them only as another added cost in a long list of hurdles and exactions that the City of Seattle imposes — almost as if it had no care in the world about the housing crisis its residents face.

If we must raise fees on homebuilders, wouldn’t the better use of this revenue be to build more affordable housing like MHA does rather than a pet list of road projects resurrected from 2018? Why create a second fee that competes with MHA for the same land value capture? And precedent would suggest expanding MHA would be paired with upzones that increase housing capacity rather than being solely a burden on builders.

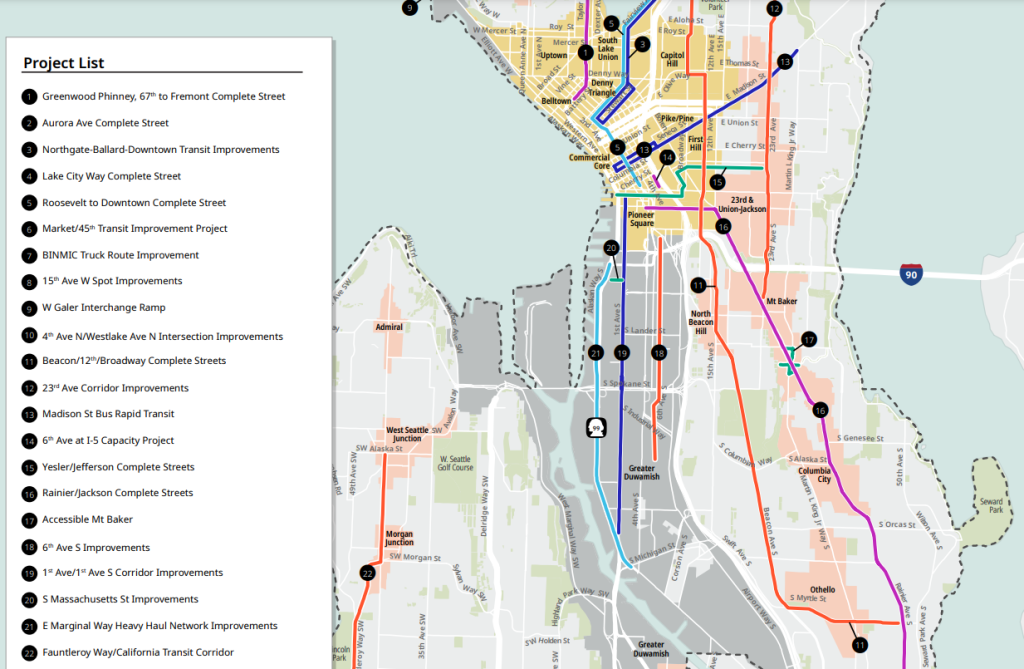

Furthermore, the proposed list of projects the council looks to advance, which they haven’t bothered to update since 2018, raises considerable questions about the readiness of this particular proposal. Increasing traffic capacity – the only allowable use of impact fees – in many of the areas included on the list looks to fly in the face of many of the city’s own stated goals around both climate and improving traffic safety. The project list has several projects that double down on the idea that one more lane or a quicker signal will solve traffic messes while ignoring the need for safer streets that encourage people to walk, roll, or bike. This project list does not live up to the City’s espoused values around safety and climate action.

Supercharging the interchange at the south end of the Ballard Bridge is one example of a misguided project. Since the list is now five years old, the list also includes projects like the RapidRide G on Madison Street that are already funded and nearing completion.

As Ryan Packer reported for The Urbanist: “The list includes a number of projects designed to improve vehicle throughput, often in the guise of improving freight capacity. A $12 million project along 1st Avenue S in SoDo, for example, promises to ‘improve operating efficiency and safety for all modes by adding extensive intelligent transportation systems including traffic cameras, vehicle detection, and traffic responsive signals,’ according to the project description. A speed study from January on 1st Avenue S, northbound at Spokane Street, found one in four drivers exceeding 35 mph (the signed limit is 30 mph) and one driver, on average, topping 70 mph per day. What exactly the ‘operational’ improvements could be made to the street that are in line with the city’s safety goals are unclear.”

“Some projects seem even more blatantly at odds with the city’s decade-old climate action plan, which called for an overall reduction in the number of miles traveled in the city by 2030,” Packer continued. “A $50 million project to ‘build capacity’ to 6th Avenue at I-5 near Yesler Way doesn’t even seem to have any nexus with active transportation. It’s not clear at all how connected this project list is with the Seattle Transportation Plan, intended to be integrated with the 2024 update to the City’s comprehensive plan, given the fact that most of the projects on this list appear to have been sitting on a shelf for a very long time.”

Overall, the City of Seattle would be better off focusing on crafting a good transportation levy package that convinces voters to support it rather than the shiny object that impact fees represent. Property tax levies are some of the most stable revenue sources around, whereas impact fees are extremely volatile, unreliable, and susceptible to market downturns that they may help precipitate.

Backers can claim this legislation is just a procedural step, but adding a provision into the Comprehensive Plan that states Seattle will “use impact fees” and approving a $1.6 billion project list seems like a very definitive step to take that will tie the hands of the next council.

Seattle has so many real problems to solve. It’s really discouraging that several councilmembers are staking their legacies and wasting time on solving an invented problem. Decades from now, history will remember what Seattle’s leaders did to address the housing crisis. It will not smile so kindly on councilmembers who made the housing crisis worse in the name of saving wealthy homeowners a couple dollars on their property tax bills and sticking it to developers.

The editorial board consists of Rubén Casas, Linda Hanlon, Ryan Packer, and Doug Trumm.

The Urbanist was founded in 2014 to examine and influence urban policies. We believe cities provide unique opportunities for addressing many of the most challenging social, environmental, and economic problems. We serve as a resource for promoting and disseminating ideas, creating community, increasing political participation, and improving the places we live.