Tacoma has the least tree canopy in the Puget Sound Region. Residents experience this reality in higher average temperatures and poor air quality.

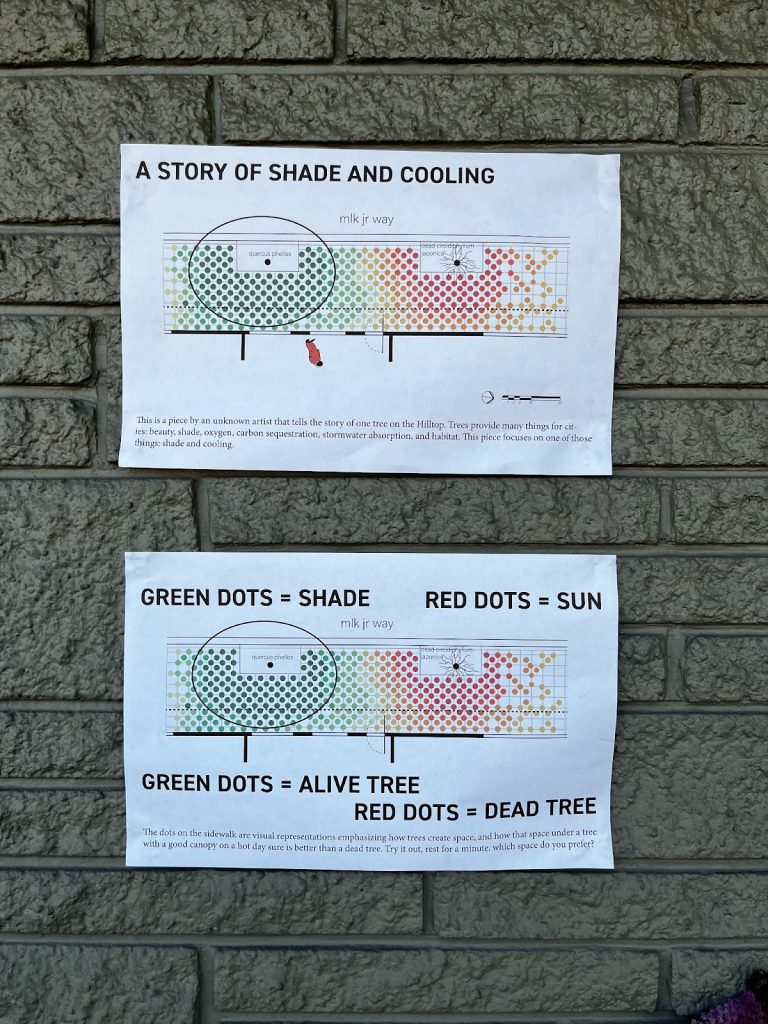

On a recent walk through the Hilltop neighborhood, I came across a stretch of sidewalk decorated with polka dots, each about a foot in diameter and spaced about half-a-foot apart. The dots were different colors: On the south end of the eight-meter stretch, the dots started out a bright cerulean green; a few feet in, they turned yellow, then orange, then red.

Public art is a defining feature of the Hilltop neighborhood, especially art with a social angle. And while these dots added whimsy to the urban landscape of the neighborhood, they were there to convey a serious message: Much of Tacoma experiences a heat island effect during warm, summer days.

Cities often experience this effect, where average air temperatures are higher and air quality is lower relative to non-urban areas, because some urban neighborhoods were built in a fashion that traps heat and polluted air. While it is true that cities must have roads, housing density, and other types of infrastructure that replace open spaces and waterways, it is also true that legacy planning and development schemes have neglected to include these in ways that would reduce instances of the heat island effect — particularly in lower-income communities of color like Hilltop.

In an era marked by climate change and worsening weather — think days-long heat waves and summers shrouded by wildfire smoke — the heat island effect emerges as a significant threat to residents of Tacoma. But there are measures cities can take to mitigate this effect, and the polka dots, put down as a gradient representing the relationship between average temperature and the presence or absence of tree shade, calls our attention to these measures.

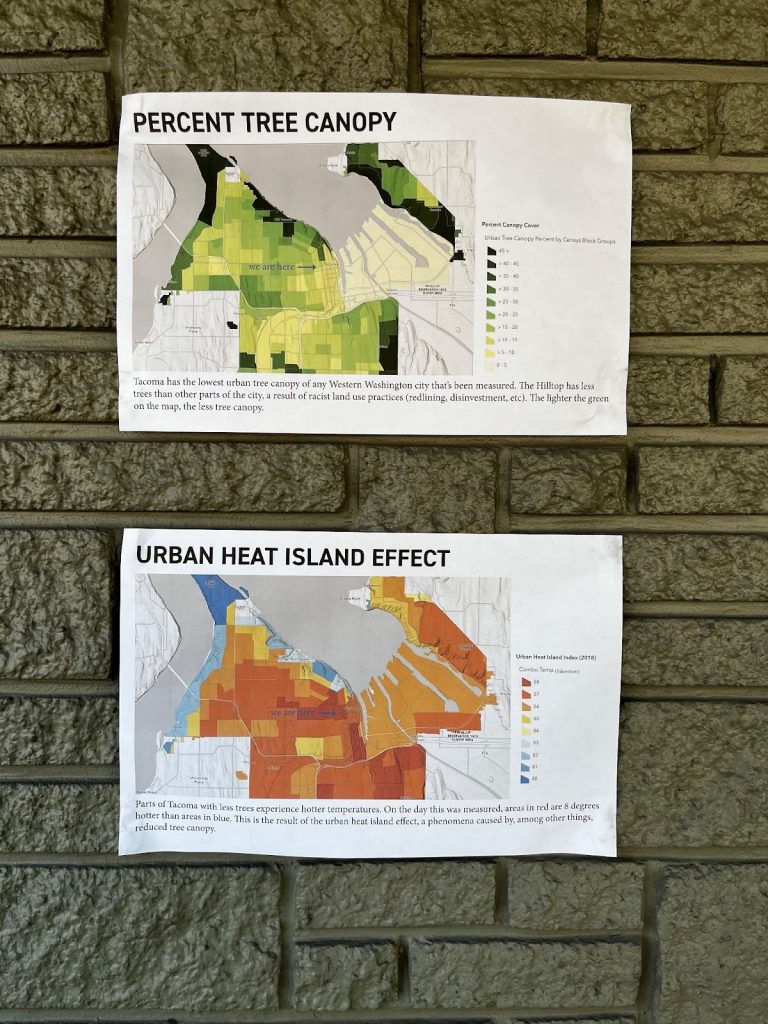

A sign on the wall adjacent to the sidewalk with the polka dots shows a map of Tacoma, where the majority of Tacoma is shaded in red — the same red as the red polka dots on the sidewalk nearby: “On the day this was measured, areas in red are 8 degrees hotter than areas in blue. This is the result of the urban heat island effect, a phenomena caused by, among other things, reduced tree canopy.”

The areas shaded blue on the map? The waterfront along Foss Waterway, Point Ruston, and the West End.

Trees represent one of the most effective tools cities have to combat the heat island effect. Other measures include reducing the width of roads and pairing these with higher buildings that cast shade over them; using heat-absorbing building materials in the construction of new buildings; and putting down more reflective pavement.

Tacoma should pursue all available measures to reduce the heat island effect, which includes redesigning roads so that they are narrower and regulating building heights so that they shade roads below.

In the scheme of things, it seems easier and more cost effective to plant more trees across Tacoma, especially in areas of the city with scarce tree canopy. We must also maintain our existing tree canopy, scarce as it is across most of the city, because any new planting will take years if not decades to mature into a robust urban forest.

A 2018 assessment of urban tree canopy throughout Puget Sound funded by the USDA Forest Service Urban and Community Forestry Program and administered by the State of Washington Department of Natural Resources found that Tacoma has “the least amount to tree canopy as a percentage of land cover for all other communities assessed in the Puget Sound Region.”

Only 20% of land area in the City of Tacoma is covered by tree canopy. This disparity in coverage aligns with other forms of exclusion and inequity in the city so that those residents who are most impacted by a lack of trees and therefore by the heat island effect are residents of color and those living in poverty.

Indeed, while some parts of Tacoma enjoy up to 64% tree canopy cover, others suffer with coverage of at most 3%.

By comparison, Seattle’s most recent tree canopy assessment found the city was at 28% tree canopy, shy of its 30% target, but still well ahead of Tacoma. Bellingham reports 40% tree cover, and Bellevue also has a target of 40%, and has nearly reached it.

The City of Tacoma recognizes that, per the results of this assessment, there is ample opportunity to grow our urban tree canopy. According to the City’s webpage on canopy cover, this information is useful as we work towards “protecting and expanding its urban forest resource, while also targeting areas to concentrate future efforts based on needs, benefits, and available planting space.”

This language suggests that mitigating the heat island effect with trees in Tacoma is a dual-pronged approach: We must protect – and expand – our urban forest. This dual-pronged approach requires putting things in the ground, and making policy that will serve existing and future trees.

Until recently, the City of Tacoma did not count with a policy or code mechanism through which to actually protect or expand the urban forest. Until August of this year, the Tacoma Municipal Code only weighed in on pruning and the maintenance of trees in the public right-of-way. An update to Title 13 of the code now carries five objectives related to trees:

- Planting More Trees – Implementing Complete Streets and Urban Forestry policies related to street trees.

- Planting Better – Optimizing Urban Forest benefits by enhancing plant selection, planting location, setback and installation requirements.

- Enhancing Urban Forest Health – Optimizing Urban Forestry benefits by better ensuring health, survival and proper maintenance of trees, shrubs, and other vegetation.

- Providing Incentives and Flexibility – Incorporating flexible code approaches tailored to the needs of differing land uses, while promoting a healthy urban environment.

- Providing an Understandable and Predictable Approach – Increasing the ease of use by providing consistency and clarity, as well as developing the Urban Forest Manual guidance document.

The Urban Forest Manual referenced in the last objective on this list is perhaps the most robust tool of this new update, as it is meant to guide planning and development in the city moving forward, and at a crucial moment for the city as it looks to add density through the Home in Tacoma Project.

The Urban Forest Manual is the closest thing to a proper tree ordinance the City of Tacoma has ever had. Tree ordinances are crucial to a city’s or municipality’s tree-related goals. A true tree ordinance is not only a guidance tool, it also provides for strong enforcement mechanisms that are applied when aspects of the ordinance are violated. A true tree ordinance also provides clear and direct indications as to who is responsible for planting and maintaining trees over time.

Without enforcement mechanisms, the work toward maintaining and expanding urban tree canopy is at risk of happening unevenly and piecemeal. Take the situation in the Hilltop neighborhood, which is what motivated a concerned citizen-artist to create the awareness-raising installation there.

The polka dots on the sidewalk directly correspond to the shade that one street tree along that stretch of sidewalk is providing. Compared to a dead or dying tree just a few feet away, one barely needs the visual aid of the polka dot gradient to see how much shade this young tree is providing.

This particular young, healthy Willow oak (quercus phellos) was planted in 2014 as part of the Hilltop Diversitree Program. It was to be removed as part of the ongoing work happening on Martin Luther King Way in relation to the expansion of the Sound Transit T-Line, specifically via the Trees for Opportunity Program.

It seems the height of irony that one city program puts trees into the ground, and not a decade later, another removes (or proposes to remove) them. Yet, this is a common occurrence in cities. Whereas a Willow oak could live for hundreds of years outside the city, this quercus phellos was to be cut down before it reached its 10th year.

Regarding the impact of the Tree Opportunity Program on the Hilltop neighborhood, a representative from the City of Tacoma provided these figures:

- Number of trees to be removed for being within the construction zone: 82

- Number of trees (planned) to be planted within the construction zone: 146

While more trees will be planted than removed — 64 more — it remains to be seen whether these new trees will be mature enough to provide shade. Removing mature trees from the right-of-way, even if they are replaced with news ones, has a negative impact on neighborhoods, and it sets us back in growing a mature urban forest.

For now, the Willow oak on MLK remains. The necessary sidewalk improvements were made without requiring its removal. Local business owners and neighborhood residents raised concerns with the city regarding this tree — specifically whether it was necessary and advantageous to remove a tree even if it was to be replaced with a younger specimen.

Not all trees in Tacoma are so lucky. Our culture and ways about trees must change so that when there are not vocal residents and business owners to raise their voice about the city’s trees, policies and ordinances are there to do that work for them.

Between the stresses of being planted and growing in a city, along with the lack of proper tree protections and enforcement, it is no wonder that the typical urban tree only lives between 19 and 28 years, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In Tacoma, it seems trees in some locations are lucky to live that long. The Willow oak on MLK that was to be removed is itself a replacement tree for one planted at this exact site in 2011. And that 2011 tree? It was a replacement tree for one planted in 1998.

This is the sad cycle of the urban tree. In Tacoma, this is a cycle that counters our goals of protecting and expanding the urban forest. And that is if trees are planted to begin with.

Tacoma has said that it means to plant “One million trees” in the coming years. This is a laudable and necessary goal. But what good is it to plant trees if we’ll only let them stand for a decade or less? Or if we do not put them in the ground at all when revitalizing or developing parts of the city? The redevelopment of the downtown area now known as the Brewery District is one recent redevelopment project that does little if anything to advance our urban forest goals.

The livability of a city is directly connected to our ability to coexist with trees. In Tacoma, we have work to do in terms of trees. This work is essential; it connects with our ability to thrive and to survive amidst a changing climate. It also connects with equity and with our desire to be a more just and less racist place.

As Luke Vannice, the citizen-artist who put up the art to call awareness to the heat island effect and the ironic cycle of tree planting and tree removal that is happening in Hilltop states, “by creating awareness about the benefits of one tree on the Hilltop, conversations can continue about the importance of urban tree canopy and the many benefits they provide. This is a wish for a day when green infrastructure is prioritized in Tacoma.”

A tree grows in Tacoma. May it stand for more than nine years.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.